Less

Less

by Andrew Sean Greer

Published by Lee Boudreaux Books

Published July 18, 2017

Fiction (humor)

272 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

July 28, 2017.

I have been an admirer of the fiction of Andrew Sean Greer since reading his first novel, The Path of Minor Planets, in 2001. It and the three novels that followed it (The Confessions of Max Tivoli, The Story of a Marriage, The Impossible Lives of Greta Wells) were set in the past.

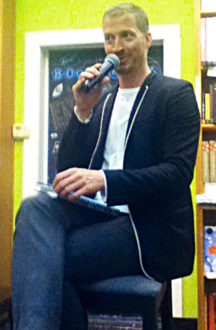

His new novel, Less, differs from the earlier ones in being set in the present and in being a comic novel. At the San Francisco book launch, Greer explained that instead of historical research, this time his research was travel to the multiple locations that the protagonist (but not narrator), Arthur Less goes: from San Francisco around the world via New York, Mexico City, Turin, Berlin, Paris, Morocco, India, and Kyoto before returning to the Vulcan Steps of San Francisco. He said that everything about those places that he included in the book were based on his own observations but that the characters and happenings are fiction.

Greer was born in November of 1970, so is not yet on the cusp of age 50, as Arthur is, and his mother is not only alive but was in the audience. She was called upon to answer a question by her son, The Writer. His twin brother was also there, along with the brother’s wife and many friends.

Greer has taught at the Berlin Free University and won a literary award in Italy (the Fernando Pivano, though I think Arthur’s experience is based on being a finalist for the Premio Gregor von Rezzori at the Festival degli Scrittori, which used to be given in the Vallombrosa monastery).

Greer has taught at the Berlin Free University and won a literary award in Italy (the Fernando Pivano, though I think Arthur’s experience is based on being a finalist for the Premio Gregor von Rezzori at the Festival degli Scrittori, which used to be given in the Vallombrosa monastery).

Arthur has just had his most recently written novel rejected by the publisher who earlier claimed that he was part of the press’ family. Arturo’s modern-day version of Calypson (Kalypsô), with a male Calypso, was well-received and has devoted fans, especially in Italy (making Arthur believe that the translator improved on what he wrote). Arthur remains in the shadow of his long-term (15 years) lover, Robert Brownburn, a leading figure in the “Russian River School” (I find the notion of one very funny).

Robert left his wife to live in a shack on the Vulcan Steps with Arthur, who had many tricks and affairs before they separated. (There is another gay couple in which the men agreed to a ten-year contract, renewed it once, and have just split before one of them (Lewis) adds Arthur to a deluxe Moroccan trip.)

Having been tolerated as the whim/boytoy of a genius, Arthur, whose looks are fading, is not very confident that he is a good writer (“great” is not even under consideration by him). When his own younger fuck-buddy, Freddy Pelu, breaks off their non-cohabitating relationship after nine years and gets engaged to another man, Arthur decides to flee—to flee not only Freddy’s wedding, but the dreaded turning 50.

Arthur experiences a series of humiliations, though also receives validation as a writer and as a man whom other men still want to bed. There is an affair with a business student through most of Arthur’s tenure lecturing in German (a language he believes he speaks well; not only is this a delusion, but his Berlin affair-mate tells him that his German is worse at the end of five weeks in Berlin than when he arrived) and a luminous connection with a Spaniard during a brief layover in Paris.

I was hoping that the Moroccan guide would bed the last member of the group still standing but did not guess the finale, though I shouldn’t have been surprised by another pun on “less” that is its last line.

At Books Inc., Greer read a passage from the Paris party in which Arthur is told that he is a “bad gay,” albeit a good writer, and an eloquent statement on the passing of time and impossibility of imagining anyone as they were before the first time the observer met them (from Robert, who also remarks that turning 50 “isn’t all bad. It means now people will think you were always a grown-up. They’ll take you seriously.”).

At Books Inc., Greer read a passage from the Paris party in which Arthur is told that he is a “bad gay,” albeit a good writer, and an eloquent statement on the passing of time and impossibility of imagining anyone as they were before the first time the observer met them (from Robert, who also remarks that turning 50 “isn’t all bad. It means now people will think you were always a grown-up. They’ll take you seriously.”).

There are nearly as many aphorisms as pratfalls in the book. Ones early on that I especially liked is “So many people will do. But once you’ve actually been in love, you can’t live with ‘will do’; its worse than living with yourself” and “Living with a genius is like living alone with a tiger.”

I was troubled by how the narrator (any narrator other than Arthur himself) could have known of the details of Arthur’s memories or of the trip, and ye olde “problem of perspective” still bothered me when I found out who the narrator was in the last chapter. But I was more than willing to go with the flow and be entertained by Arthur’s misadventures and self-denigrations.

Though often very funny, the book illuminates quandaries of love, relationship, literary reputations, caddish behavior (to not by Arthur), and even with the cherry blossoms still buds, evanescence.

And and shows that running away is, sometimes, productive.

© 2017, Stephen O. Murray