The Lesbian Paperback

Part 2

by Barbara Grier

writing as “Gene Damon”

Photograph courtesy JEB[1]Barbara Grier image ©2017 by JEB (Joan E. Biren.) Used by permission.

Printed in the July 1966 issue of Tangents

pp. 13–15 • Reader At Large column #10

See part 1, printed in the June 1966 issue of Tangents

Several dozen titles appeared, primarily between 1957 and 1962, which fall into the worthless category because of too much melodrama, too much sex, violence, sadism, etc…. but which also contain some good elements.

An example of these many novels which fall into a kind of limbo between the top and the bottom (literally and figuratively) in the field is The Censored Screen, by Brian Dunn (Newsstand Library, 1960). The book features so much junk it’s actually silly but, buried in all this, is a constructive, romantic and very moving love story. About the same time many well-known professional pulp writers, with acknowledged plotting ability, got on the lesbian literature band-wagon—some of them (those with some rudimentary knowledge of feminine psychology) doing a creditable job. An example of this group is Scandal In Suburbia, by Gardner F. Fox (Hillman Books, 1960).

1961 brought Artemis Smith’s third and last book to date. As mentioned previously it was very poor, despite a sympathetic outlook and her undeniable writing talent. The plot was pure hokum, and the title, This Bed Was Made (Monarch), seemed an ironic jibe at the author.

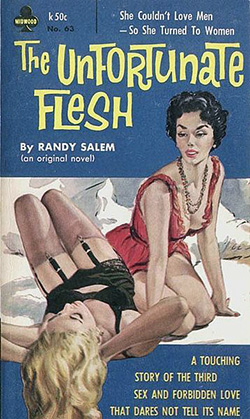

Randy Salem’s The Unfortunate Flesh (Midwood Tower, 1960, 1961) continued her happy-ending soap operas, and this one introduced a rival to Beebo Brinker in Jesse Cannon, a six-foot aristocrat. Unfortunately, Salem never used Jesse Cannon in a subsequent novel.

An excellent first novel, never honored by a second, appeared in 1961, Twilight Girl, by Della Martin (published by Beacon). The quality in this makes it possible to believe that Della Martin is the pseudonym of an established author. In any case, Twilight Girl includes references to obscure literature, etc., that one does not expect in a paperback original.

Both Sloane M. Britain and March Hastings continued their prolific output, each contributing several titles in 1960 and 1961, ranging from very poor to fairly good. Britain’s These Curious Pleasures (Midwood Tower, 1961) is clearly autobiographical. (She subsequently committed suicide.)

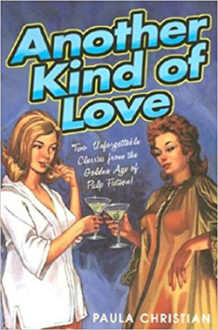

Paula Christian had two novels in 1961: Another Kind of Love, published by Fawcett Crest, and Love Is Where You Find It, published by Avon. These two established her as one of the really important contributors. The books appeared within weeks of each other. Love Is Where You Find It overshadowed Another Kind of Love because it was very reminiscent of Gale Wilhelm’s Torchlight To Valhalla, not in style, but in storyline. Paula Christian definitely out-plots the other major writers in the field though she is not nearly as good a writer as Valerie Taylor. During their peak years, a marriage of their talents might have been fortuitous for both of them.

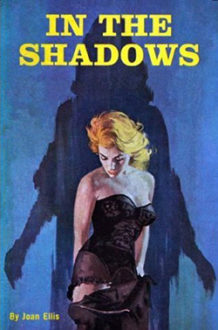

The last big year for lesbian paperbacks was 1962, and the number of good titles was truly remarkable. There were so many that only a few can be mentioned here. Joan Ellis’ In the Shadows, published by Midwood Tower, was well done, and the characterizations in her book, Gay Girl, also published in 1962 by Midwood Tower, were excellent. An unusual approach coupled with slick writing marked My Lovely Adele, by Adrian Bennett (Avon, 1962). This one made use of a male narrator successfully—a very difficult approach.

Miriam Gardner’s The Strange Women (Monarch Books, 1962) was over-plotted. This is doubly unfortunate since in its original manuscript form it was many hundred pages longer and intended for a quality market. The bones left in this edition are bleak beside the original, but the story is miles beyond the average paperback in depth psychology and character motivation.

Miriam Gardner’s The Strange Women (Monarch Books, 1962) was over-plotted. This is doubly unfortunate since in its original manuscript form it was many hundred pages longer and intended for a quality market. The bones left in this edition are bleak beside the original, but the story is miles beyond the average paperback in depth psychology and character motivation.

Two good titles came from the pen of the soap opera girl, Randy Salem, who could have, with persistence, risen from that category. Both Tender Torment and The Soft Skin, published by Midwood Tower in 1962, are well worth owning.

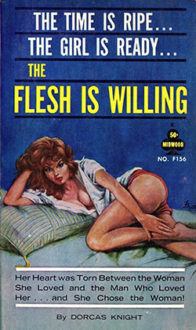

The Flesh is Willing, by Dorcas Knight (Midwood Tower) utilizes the Southern small town setting and lush atmosphere to bolster the effectiveness of the slight story. Professional writer Bonnie Golightly (who sued Truman Capote over his novel, Breakfast At Tiffany’s) contributed The Shades of Evil (Hillman Books), which also used the Southern exposure technique. This one is as important to the male audience as the female and is, incidentally, an excellent mystery.

Ann Bannon’s last (to date) of her personal series of novels, Beebo Brinker (Fawcett Gold Medal), was a sad failure. It is mentioned here only because Bannon’s books must all be read for the correct impression. Actually, the most interesting years in the life of the fabulous Beebo have not yet been told—the time between her first successful affair with Paula and her famous seduction of Laura in the second book of the series, I Am A Woman.

The unsympathetic but fascinating Harriet, by Tom Karsell (Avon, 1962), uses the multiple viewpoint technique to portray a stunner—bitch, butch and all— but quite a girl.

The crowning novel of 1962 was Shirley Verel’s The Dark Side of Venus (Bantam). Sadly, this was a hardback in England and thus falls outside the scope of the article because it was only stupidity on the part of the American publishers that kept this out of hardcover in this country.

Although several of the better writers in the field contributed books in 1963, the end of the era was in sight and the number of good titles dropped sharply.

Paula Christian’s This Side of Love (Avon, 1963) was a sequel to her first novel, Edge of Twilight (1959), though her fourth paperback appearance. It was and is an excellent novel, helped by literary freedoms in 1963 which were not yet apparent in 1959.

My Sister, My Love, by Miriam Gardner, published by Monarch, included mild lesbian incest, always a questionable subject, but was very well-written.

Randy Salem had two entries for the year: Honeysuckle and The Sex Between, both published by Midwood Tower. The former was very good, the latter only so-so. Honeysuckle convincingly examined the “dog days” possible in any kind of marriage, a different approach and a welcome relief from the overuse of glamorous surroundings in lieu of talent.

Ann Aldrich launched her last damnation, We Two Won’t Last (Fawcett Gold Medal), but it was mellower than the earlier titles and not so unwelcome.

A minor but good enough March Hasting’s title, The Heat of Day (Midwood Tower), and Valerie Taylor’s Unlike Others (also published by Midwood Tower), rounded out the declining year. Nothing needs to be said about the Hastings’ book, but Valerie Taylor’s title was poorly- plotted and saved only by her writing skill.

A minor but good enough March Hasting’s title, The Heat of Day (Midwood Tower), and Valerie Taylor’s Unlike Others (also published by Midwood Tower), rounded out the declining year. Nothing needs to be said about the Hastings’ book, but Valerie Taylor’s title was poorly- plotted and saved only by her writing skill.

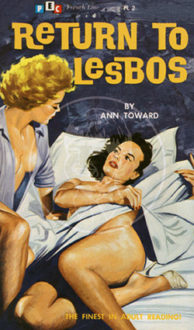

Ironically, the year 1964, which really proved the sun was setting on this special genre, opened with Valerie Taylor’s Return to Lesbos, published by Midwood Tower. This was the almost necessary sequel to the 1960 title, Stranger on Lesbos. The sequel was lovely, romantic, much happier and, as one had come to expect from Valerie Taylor, beautifully written—but the magic missed somehow and it was less than the original. And on an even more downhill note, this book was followed by A World Without Men, by Valerie Taylor (also published by Midwood Tower), in which the action pre-dates Return to Lesbos from an entirely different standpoint. It was well-written, but out of step.

The only other paperback of enduring value from 1964 was Twilight Lovers, by Miriam Gardner (Monarch, 1964).

1964 did have the usual complement of filthy titles, hundreds of them, and perhaps a dozen “passing fair” entries, easily read, easily forgotten.

1965 opened with Valerie Taylor’s Journey To Fulfillment (Midwood Towers). This novel belongs in the belated series Miss Taylor created toward the end of her career.

The history of this series is peculiar enough to warrant outlining it here. The first novel of the series, Stranger on Lesbos (1960), introduced Frances Ollenfield as one of the two major characters. In the sequel, Return to Lesbos (1964), Frances ends up happily with Erika Frohmann. Then in the next book, A World Without Men (1964), Erika Frohmann’s life just prior to meeting Frances is explored. In the final novel, Journey to Fulfillment (1965), Erika’s early life from childhood on is covered. So the series was inverted in time; a very poor way to hold an audience, and it failed to be as interesting as it undoubtedly would have been had the order been reversed.

The history of this series is peculiar enough to warrant outlining it here. The first novel of the series, Stranger on Lesbos (1960), introduced Frances Ollenfield as one of the two major characters. In the sequel, Return to Lesbos (1964), Frances ends up happily with Erika Frohmann. Then in the next book, A World Without Men (1964), Erika Frohmann’s life just prior to meeting Frances is explored. In the final novel, Journey to Fulfillment (1965), Erika’s early life from childhood on is covered. So the series was inverted in time; a very poor way to hold an audience, and it failed to be as interesting as it undoubtedly would have been had the order been reversed.

Paula Christian had two novels published in 1965, The Other Side of Desire (Paperback Library) and Amanda (Belmont Books). Both were far below her usual standards. That they were better than hundreds of others that year isn’t necessarily a recommendation.

There were a few others worth reading such as March Hastings’ Abnormal Wife (Softcover Library) and Women Like Me, by Donna Richards (Lancer Books).

One really good novel, Enough of Sorrow, by Jill Emerson (Midwood Tower), mercifully brightened a generally sad picture.

The era began in 1950 and ended in 1965. Hopefully, in many memories, some names will remain bright for years to come: Valerie Taylor, Ann Bannon, Paula Christian and one or two others. But for now; Ave Atque Vale!

—GENE DAMON

©1966, 2018 by The Tangent Group. All rights reserved.