The Lesbian Paperback

Part 1

by Barbara Grier as “Gene Damon”

Photograph courtesy JEB[1]Barbara Grier image ©2017 by JEB (Joan E. Biren.) Used by permission.

Printed in the June 1966 issue of Tangents

pp. 4–7

See part 2, printed in the July 1966 issue of Tangents

The boom in publishing today is the paperback novel. It is not new, except relatively, and it is not indigenous to the United States. In Europe most books are paperbound, except for special editions, though they are usually printed on good stock with margins suitable for rebinding. In 1939, the paperback industry, as we know it now, began in the United States; and it has grown to be one of the biggest factors in publishing.

From the publisher’s standpoint, of course, the large number of lesbian paperback originals is a “strictly for money” proposition. The vast majority of these titles are pointless filth—too poor to even consider censoring—and are directed to a voyeur-minded, heterosexual male audience. Beginning in 1950, however, a small nucleus of “good” titles appeared. They were good within specific limitations. Few of them would qualify as good in a literary sense, although the better range from competently to quite well-written.

Plot-wise they became monotonous since, as one non-fiction reading friend of mine once remarked, “There are just so many ways to tell the same love story.”

In 1966 it seems clear that the era of good lesbian paperbacks is about over. The increased freedom in literary expression (ironically assisted by these paperbacks) has pretty thoroughly obliterated the need for paperback novels exclusively dealing with lesbians. It is interesting, also, to note that now that the lesbian field is dying (at least those with some actual merit), the male homosexual paperback original is becoming a booming business. It will be enjoyable to watch the end of this trend as well, when the hardback field opens the way to more complete male homosexual novels.

The good lesbian paperbacks served a definite purpose by satisfying vicariously the need for “happy endings” which are so often lacking in the more literate treatments of the subject. They also provided generally youthful, theoretically romantic figures and contemporary settings. To some extent they were responsible for better public relations with the general public.

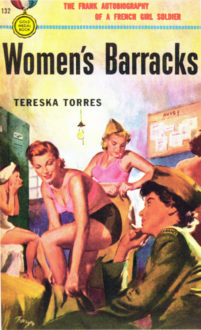

The first to appear was, ironically, one of the finest. Women’s Barracks, by Tereska Torres (Fawcett Gold Medal, 1950, etc.) This has become very well known and it is reprinted every year or so. It once was the subject of intense censorship. This appears rather funny in view of the dozens of later titles. The story deals with life in the French women’s army during the 1940’s and treats lesbianism from several angles, quite honestly and sympathetically. Tereska Torres has gone on to produce a string of successful hardcover novels, all variant or lesbian to some extent.

The first to appear was, ironically, one of the finest. Women’s Barracks, by Tereska Torres (Fawcett Gold Medal, 1950, etc.) This has become very well known and it is reprinted every year or so. It once was the subject of intense censorship. This appears rather funny in view of the dozens of later titles. The story deals with life in the French women’s army during the 1940’s and treats lesbianism from several angles, quite honestly and sympathetically. Tereska Torres has gone on to produce a string of successful hardcover novels, all variant or lesbian to some extent.

Vin Packer’s highly unsympathetic, but very well-written Spring Fire was published by Fawcett Gold Medal in 1952. This was one of the first to incorporate the specific sexual scenes generally included for several years and it was a bestseller. Today it simply wouldn’t have the appeal it did then because of subsequent developments in the field, but it was quite a pioneer and influenced Fawcett’s Gold Medal line of books for years. That same year, 1952, Fawcett published two much more sympathetic and considerably less sensational titles, Nancy Morgan’s City of Women and Fay Adams’ Appointment in Paris. Nancy Morgan’s book was a “women in war” title. Fay Adams’ book remains one of the better minor titles—oddly it was not much noticed and never reprinted. A good sound copy of it today is worth $5.

In 1954, Ace Books brought out Wilene Shaw’s The Fear and The Guilt. This was a miserably unhappy book but the unusual setting and characters make it a stand-out even today. It is lesbian love, hillbilly style, and well handled.

1955 saw the first of the noisy nasty titles of the brilliant, but deliberately cruel, Ann Aldrich. Her We Walk Alone, Fawcett Gold Medal, became a best-seller fast and still has an audience although one wonders why. (Ann Aldrich is also Vin Packer.)

John Wyndham’s lovely science fiction tale, Consider Her Ways, was published by Ballantine in 1956. This was about a world of women only and it is a good book if a wee bit far out for serious consideration in this column. During these first six years from 1950 to 1956, some others appeared, too poor to mention here and the general forerunners of today’s several-a-year all tripe type.

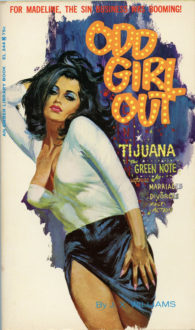

The year 1957 began the big boom which foreshadowed the inevitable saturation point. Titles began to vary and at the same time the “set patterns” sympathetic and contemporary titles began to appear. New writers came on the scene and became quite4 famous in a few years’ time. One of the first books of that year was Odd Girl Out, by Ann Bannon, published by Fawcett Gold Medal. Set in a college, as so many are, this began a series of titles with rest on the bookshelf of virtually every even faintly literate lesbian. Ann Bannon can write competently and can hold the reader’s attention. This first novel does not compare with her later ones; it had all of the requirements: youth, sex, love, sex, hope, sex, and no real lack of sympathy. Some touches of psychological insight begin creeping into the titles about then and this added fuel to the selling fire.

The year 1957 began the big boom which foreshadowed the inevitable saturation point. Titles began to vary and at the same time the “set patterns” sympathetic and contemporary titles began to appear. New writers came on the scene and became quite4 famous in a few years’ time. One of the first books of that year was Odd Girl Out, by Ann Bannon, published by Fawcett Gold Medal. Set in a college, as so many are, this began a series of titles with rest on the bookshelf of virtually every even faintly literate lesbian. Ann Bannon can write competently and can hold the reader’s attention. This first novel does not compare with her later ones; it had all of the requirements: youth, sex, love, sex, hope, sex, and no real lack of sympathy. Some touches of psychological insight begin creeping into the titles about then and this added fuel to the selling fire.

A little later in 1957, Valerie Taylor began her career with Whisper Their Love, Fawcett Gold Medal. This one stuck to the leave them miserable at the end trend, but was a good start. Taylor outdoes Bannon literary-wise but missed the audience because she did not develop a continuing character until late in her career and, as all TV fans know, this is the road to success. But Valerie Taylor remains the finest writer in the group.

Three other interesting books appeared in 1957, but interesting for widely divergent reasons. The first, Reed Marr’s Women Without Men, again published by Gold Medal, was one of the 10 paperback best-sellers of the year among all publishing companies. This is its only claim to fame, however, for it is a biased and vituperative study. (Ann Bannon’s much superior title, Odd Girl Out, was Fawcett Gold Medal’s second-best title in sales in 1957. Considering these two titles and their selling success, it is no wonder that the company continued until recently to be the leading paperback publisher in that particular field.) The next title was a mystery whose claim to fame was having a wholly-lesbian cast, Murder In Monaco, by John Flagg, Fawcett Gold Medal (of course). To say the very least it was anti-lesbian but it was a rather wild departure from the not-so-long-ago dictum that mysteries must not concern sex or controversial topics. The third title was the very beautiful King of a Rainy Country, by Brigid Brophy, Knopf, 1957. This book is as interesting to male homosexuals as to lesbians and it is cheating in a sense to list it here since it deserved and soon earned a hardback publication.

1958 started with Ann Aldrich’s second controversial title, We Too, Must Love, Fawcett Gold Medal. This increased her audience and made her a discussion topic in every lesbian household, however, unflattering the discussion may have been. A second science fiction title devoted entirely to lesbianism appeared: Charles Eric Maine’s World Without Men, Ace Books, 1958. This one had its silly side, though, and failed to come up to the expectations of the beginning of the book. Vin Packer, the evil alter ego of Miss Aldrich, produced the nasty but well done. The Evil Friendship, Fawcett Gold Medal, 1958.

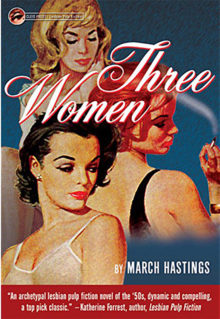

An author who has since proved to be an enigma was introduced that year. March Hasting’s first lesbian title, Three Women, Beacon, was excellent in handling, poorly plotted and too melodramatic, but polemically sympathetic. Since then, she has varied so widely that she cannot be judged. On the one band, she has several excellent novels in the field but she bas also written several of the most degrading titles. Miss Hastings is the Jekyll-Hyde of the field.

An author who has since proved to be an enigma was introduced that year. March Hasting’s first lesbian title, Three Women, Beacon, was excellent in handling, poorly plotted and too melodramatic, but polemically sympathetic. Since then, she has varied so widely that she cannot be judged. On the one band, she has several excellent novels in the field but she bas also written several of the most degrading titles. Miss Hastings is the Jekyll-Hyde of the field.

By 1959 the boom was a landslide and just checking the hundreds of titles became a full-time job. The first book out was a kind of blockbuster and still is: I Am A Woman, by Ann Bannon, Fawcett Gold Medal, 1959. This, the second of the Bannon series, introduced her larger-than-life, swaggering butch, Beebo Brinker, who carries off a barroom seduction scene that is surely a classic.

Right on the heels of Bannon’s second title, Fawcett Crest brought out Paula Christian’s first novel, Edge of Twilight. Compared to Bannon’s book, it made less splash, but it was as good a title, and in some respects, better. The women involved were somewhat more adult, and this alone was an improvement.

Lesbian paperback production didn’t let-down in 1959. Right after, the first Christian book, a novel, Chris published by Beacon, appeared. Randy Salem is the author of several books which are most easily described as soap operas for lesbians. Her people aren’t very real though they are fun to read about. Chris, in a way, was a second Beebo Brinker. She failed as a heroine to attract as large an audience because she did not possess place, position and brains.[2]See Grier’s correction of this sentence in the Aug. 1966 issue of Tangents, in the Letters column. Bannon wisely made Beebo in the fashion of Western heroes, foot-loose and fancy-free. Chris had qualms, and so she failed just a little, but it was an excellent beginning for Randy Salem.

Another debut of 1959 was author Artemis Smith with Odd Girl, Beacon, This was an unusually good book, and Miss Smith followed it a little later that same year with The Third Sex, also published by Beacon. These were so good, that her third and last book to date was a dreadful disappointment. Unlike other authors who go on to greater heights, Miss Smith never topped her first two books. After the third, she simply stopped writing. This was sad because she wrote very well, better than Bannon or Salem or Christian and nearly as well as Valerie Taylor. Once again it was a matter of gimmick. Bannon has an all-star cast full of familiar figures who go from book to book. Salem can make the peanut gallery weep. Christian plots very well and Taylor writes on a par with Gale Wilheim. Somehow Artemis fell short.

Valerie Taylor’s second novel The Girts in 3-B, published by Fawcett Crest, also appeared in 1959. Where her first book was beautifully-written and not sympathetic (the tide hadn’t really turned in 1957 and bad endings were required) The Girls In 3-B was very pro-lesbian and was equally well-written. This was still the days of too much sex in the novels, even the good ones. For a few years the field was quite unevenly split, with about 15 to 20 titles not worth mentioning for each good one. This was fine, the good writers could get into print and could push some rather strong propaganda along with entertainment. From 1960 until 1963 a number of the more experienced writers in the field cut out a good bit of the bedroom activity which had somewhat marred the earlier books.

Many other titles of value appeared in 1959. March Hastings published several of her now up, now down, books. Ann Bannon’s third title and poorest, Women in the Shadows, Fawcett Gold Medal, seemed to be the end of the Bannon series. Fortunately, this was not the case.

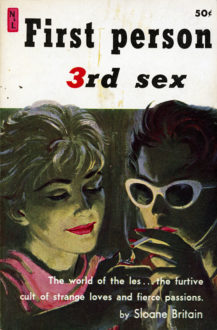

Another odd debut came in 1959, when Sloane M. Britain’s first novel, First Person, Third Sex, Newsstand Library, appeared. The book featured adults in the 30 to 70 year range, a very unusual facet for a paperback since most of them feature young people in line with the American youth-cult idea. It was a welcome change to read about people with mature concerns such as jobs and futures. This book was so good that the many poor titles which later came from the pen of Sloane Britain are not explainable. Her case is similar in this respect to that of March Hastings, but Hastings never did produce even one book as good as Sloane Britain’s first novel.

Another odd debut came in 1959, when Sloane M. Britain’s first novel, First Person, Third Sex, Newsstand Library, appeared. The book featured adults in the 30 to 70 year range, a very unusual facet for a paperback since most of them feature young people in line with the American youth-cult idea. It was a welcome change to read about people with mature concerns such as jobs and futures. This book was so good that the many poor titles which later came from the pen of Sloane Britain are not explainable. Her case is similar in this respect to that of March Hastings, but Hastings never did produce even one book as good as Sloane Britain’s first novel.

From 1960 to 1962 the quantity of titles became enormous, ranging in the hundreds each year, but the good ones remained small in quantity —growing proportionately, of course, but few enough to be within the book budget of any collector.

The third Valerie Taylor book appeared in 1960, Stranger on Lesbos, Fawcett Crest. The first half of this book is moving and literate and had it ended as well as it began it would be the all time best in paperbacks.

Ann Bannon’s fourth and fifth titles, Journey To A Woman and The Marriage, both published by Fawcett Gold Medal in 1960, dispelled any thought of failure inspired by the third book in the series. The inclusion of an excellent character, Jack Mann, in these titles make them all of interest to the male audience.

Somewhere in this article mention of Sheldon Lord’s entertainments is necessary. This is a male-oriented writer who writes anti- and pro-lesbian novels apparently effortlessly (dozens of them). Many contain good portraits—for example, A Woman Must Love, Midwood Tower, 1960.

Carol In A Thousand Cities, by Ann Aldrich, Fawcett Gold Medal, 1960, was Miss Aldrich’s third attempt to run down her relatives. In many ways she failed in her effort since the book is primarily an anthology and although her personal contributions were as unpleasant as ever, she did include some of the finer items written by others in the field.

©1966, 2017 by The Tangent Group. All rights reserved.