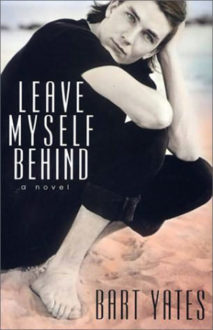

Leave Myself Behind

Leave Myself Behind

by Bart Yates

Published by Kensington

Published March 1, 2003

Fiction (youth/romance)

256 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

December 20, 2003

I was immediately engaged by the smart-mouthed narrator of Bart Yates’ novel Leave Myself Behind: Noah York, a seventeen-year-old uncertain about his sexuality but very certain in his literary judgments and in his intellectual superiority to other seventeen-year-olds.

At the start of the novel, Noah’s father has died and his mother, Virginia, a writer of very difficult, and allusive poetry, has taken a teaching position at Cassidy College in Oakland, New Hampshire, and bought a large house in need of renovation, which she and Noah undertake over the summer before she starts teaching and he submits to a senior year in high school in an unfamiliar place. (The reader learns nothing about Noah’s social life in Chicago, before the move, and the only person he mentions missing is his father, whose merits Noah realizes more clearly as he has to deal with his manic-depressive mother on his own.)

J. D., a sixteen-year-old neighbor, is sent over by his mother to invite the Yorks to dinner. J. D. is treated very badly by his mother and soon is helping Noah and Virginia remodeling their house. The renovators start to find Mason jars with mementos of a poet who stopped publishing in 1951 and apparently married the ogre who had owned the house and also taught at Cassidy College.

Neither Noah nor J. D. wants the stigma of being gay. This makes first love extra-difficult, especially in school after they are outed. There is a coming-out story mixed with the first-love story. There are also three mysteries involving the violations of three women in the past, plus the directly related mysteries of what happened to those women’s offsprings. Noah eventually learns about the violent episodes and their results, and what happened to two of the tree offspring.

I think there are too many parallels or echoes among the three histories/mysteries, and that the only one that yields satisfaction to mystery fans is the back-story of J.D. and his mother (Donna). The other two seem to me to be explained somewhat perfunctorily (not to mention too easily!).

The book mostly moves swiftly with mostly entertaining digressions, though there are a few flashbacks I would have cut. Nevertheless, with two minutes to spare, I finished the novel before Christmas ended.

The jacket blurb claims that Noah is “part Portnoy, part Holden Caulfield.” I don’t hear (see) Portnoy. Noah’s voice has some resemblances to Holden’s ironic, mocking voice and impatience with hypocritical adults (and surely, naming the narrator’s love J.D. is a tribute to Salinger). As engaging and entertaining as Noah’s voice is, Leave Myself Behind has a lot more plot and a lot more characters of real complexity than The Catcher in the Rye. And, at least early on, Noah has a fouler mouth than Holden did. (His use of the f-word declines markedly when he develops a sex life.) Still, it is Noah’s voice that carries the novel and supplies most of the pleasures of this text—even though Victoria gets off quite a few zingers, too.

The novel has also been compared to Dream Boy and Night Swimmer. I don’t see much resemblance other than all three showing young male-male love in a violently hostile world. The other two books are narrowly focused on one relationship, incantatory, and tragic, whereas Leave Myself Behind explores multiple stories, has many characters, and remains upbeat through a lot of violence and insanity.

I enjoyed Leave Myself Behind and gulped it down quickly. I admire Yates’ ability to sketch bad/irresponsible behavior (mostly of men) without preaching, and to balance the horrors and the humor (mostly Noah’s and J.D.’s gallows humor, along with some mordant humor from a classmate and from Victoria). Noah seems not only wise beyond his years but unbelievably well-read—even taking into account that he is the son of two literature professionals. Although his range of apt literary references strained credulity, they made for a more interesting narration than even a very precocious real seventeen-year-old could produce. As for precocious wisdom, Noah credibly makes a lot of mistakes (usually shooting off his mouth when silence would have been more compassionate and pressing when patience would have been a wiser course). Someone has to keep sane when everyone else is wigging out—at least in books—and there are cases in which the child becomes the de facto parent, so I can suspend disbelief in Noah’s emotional wisdom—‘cause I like him and enjoy how he matter-of-factly tells about an eventful summer and autumn in a haunted house and an all-too-typically homophobic high school.

(I wish Yates had learned the rules for using lie/lay or that a Kensington copyeditor had intervened to correct his frequent misuse.)

first published on epinions, 20 December 2003

©2003, 2017, Stephen O. Murray