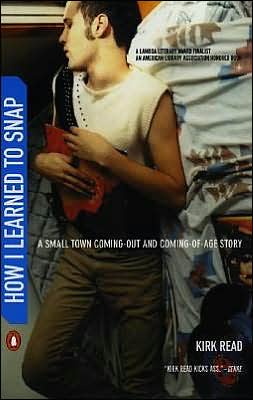

How I Learned to Snap

How I Learned to Snap

by Kirk Read

Published by Hill Street Press

Published June 2001

History (memoir)

224 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

December 20, 2001.

Born in 1973, Kirk Read grew up in the same place Pat Robertson had: Lexington, Virginia. Kirk’s father was a retired U.S. Army colonel (18 years older than Kirk’s mother). He was not just an alumnus of the Virginia Military Academy who expected his sons to follow the family tradition but the director of the VMI alumni program. Though not precisely a “chip off the old block,” Kirk, his flamboyant youngest son, seems on the evidence of his memoir, How I Learned to Snap, to have been plenty fierce. To survive and to some extent to thrive as openly gay while a student in a high school filled with “rednecks,” at the height of testosterone overdrive, he had to be fierce. To defy so many conventions in a southern American high school during the first Bush administration, he had to have an amount of self-assurance that is so rare among adolescents as to seem preternatural to me.

I’ve always thought that a sense of irony was a major gay survival tool. Kirk Read has a highly developed one. At least now, he is able to be ironic about the extent to which he was a “drama queen” in high school, sometimes unsuccessfully seeking out confrontations. He also became a dramatist queen when a play with plenty of homosexual content was chosen for production in the state capital (Richmond) in a competition for young authors. This was less big a deal than the football team winning the state championship, but, nonetheless, it was validation from outside—not only for the young writer relentlessly pursuing his own course but for his hometown. Even his father failed to comment on the homosexual content, confining himself to suggesting fewer uses of the f-word in his next play.

The gay youngster has many interests regarded as inappropriate for boys. Soccer in a rural Virginia school in the late 1980s that was winning a football state championship was somewhat suspect, but Kirk played it like a particularly vicious rugby player. And in the one (off-field) physical fight recorded in the book, he scored a knockout karate kick. The surface on which the skirmish was waged was not level like the floor was in karate school, however, and he landed ungracefully.

Learning How to Snap is comprised of 51 vignette/essays averaging 4–5 pages. The chapters are more or less in chronological order, ending with graduation from high school, but also more or less stand alone (except for some recurring characters and STOP, the school’s detention program). If there is an overall structure of the pieces other than the rough chronological one, I missed it. There is growth, but it’s not especially cumulative (as in a proper bildungsroman). There’s not a lot of arc or developing sensibility or much variation of tone or form.

The stringing together of fairly independent chapters makes How I Learned to Snap an excellent book for reading in snatches (on public transportation, for instance). Like the collections of columns by Michael Thomas Ford or the stories of David Sedaris (but unlike I’s longer essays), I think it is better read in installments of one or two pieces than in a continuous read. Best of all is to hear Kirk read them (I have heard seven or eight in public performances). Although I like the book’s typography, there should be an Audio-Book version.

There was only one chapter (“Audience”) in which the pop cultural references were opaque to me. My time in high school was served in the late 1960s rather than the early 1990s, and I know more about popular culture (at least popular music) before my time than that after my time.

Fortunately, that chapter is followed immediately by one of my favorite (“Fullbacks”), one that deals with coaching a grade-school soccer team.

The peer pressure to conform seems not much different in rural Virginia in the early 1990s than it was in rural Minnesota in the 1960s. There were more books about homosexuality somewhere out there in the world (though not in the high school library) by the 1990s, but the story of working up the nerve to get access to them sounds very familiar not just to my own but to those I have heard from other gay men recovering from their adolescences.

Kirk Read, as he readily acknowledges, was very lucky to have “parents who encouraged me to take risks… [and] who, at key moments, had the good sense to look the other way…. The whole concept of [advance] parental permission was alien to me. I always said yes, then figured out how I could talk my parents into it.” He also knows that “the name-calling and bullying I experienced were minor compared to what many kids face.” Given the disinformation about AIDS he received, he was also lucky not to be infected with HIV.

I know that at age 27 (or, for that matter, at age 19), I remembered less of what high school was like than Read does. I suspect that, for all his obvious precociousness, when he was 14 he was in harsher, less stylized pain. The extensive journals he frequently refers to having been scribbling in were, undoubtedly, aids to his memory. I’d have liked at least a representative example of what he was writing at the time. Juvenilia is embarrassing to the more skilled older craftsman (even at the ripe old age of his late 20s), but a little squirming is not too high a price to ask of someone who so reveled in making his father and school administrators squirm during his youth!

first published on epinions, 20 December 2001

©2001, 2016, Stephen O. Murray

A more recent report with a (not very good) sample of Read’s performance art:

http://archives.sfweekly.com/exhibitionist/2011/05/10/kirk-read-where-scatological-performance-art-queer-erotica-humor-and-a-big-heart-coexist