Landscape: Memory

Landscape: Memory

by Matthew Stadler

Published by Macmillan

Published Sept. 1990

Fiction

301 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

August 9, 1997.

I was captivated by Matthew Stadler’s shimmering novel of adolescence in the Bay Area in the early teens of this century, Landscape: Memory.

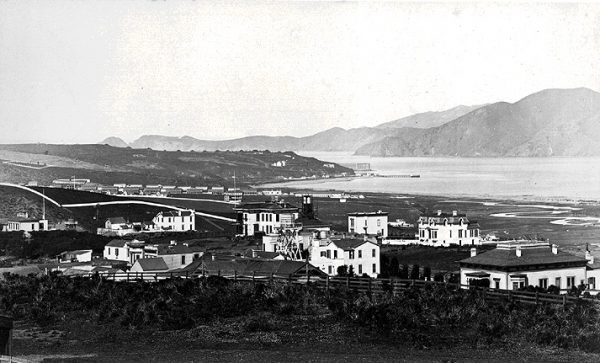

Maxwell and his friend Duncan live among other people (Max’s mother deciding to live with Duncan’s father and the boys living partly on their own, spending the summer with Max’s father in Bolinas and then going off to UCB (then simply “Cal”)), but what matters most is each other.

Perhaps Duncan feels this less than Max. We only hear from Max—in a journal that is not entirely credible (i.e., that the entries could have been made that way; the feelings and sequence are credible; Stadler did not want to tell the story in the past tense but could have put it all in Max’s consciousness without the artifice of it being a journal).

I was mostly delighted by the sensuous description of the idyllic life they lived outside conventions, with plenty of nudity and sex along with efforts to understand how memory operates. Why he is focused on the mechanics of memory is not clear. In preparation for remembering Duncan? To preserve the memory of the earthquake? The focus begins before his household reconfigures (obviously before the denouement), and there are no memories of childhood bliss in his natal family. The memories are of the 1906 earthquake. Everything else is recorded in the journal shortly after it happens.

In addition to writing, Max also aims to fix a particular vista in paint and mulls over problems of visual perspective (for drawing/painting).

A blurb invokes John Knowle’s A Separate Peace, and the narrators of both novels are less interested in world wars than in their beloved agemate. But Max is not responsible for Duncan’s death—and Stadler is the better writer. A Separate Peace certainly spoke to me once upon a time. I was so much older then?

Landscape: Memory is much more pastoral; the school matters much more in A Separate Peace. The beloved must die (if he doesn’t betray the lover or fail to respond to him in the first place): this seems to be a rule (not just white lovers in black writer’s novels).

9 August 1997

©1997, 2016, Stephen O. Murray