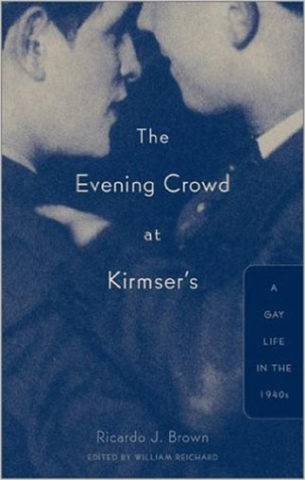

The Evening Crowd at Kirmser’s: A Gay Life in the 1940s

The Evening Crowd at Kirmser’s: A Gay Life in the 1940s

by Ricardo J. Brown

edited by William Reichard

Published by University of Minnesota Press

Published August 7, 2001

History (memoir)

176 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

November 18, 2001

The Evening Crowd at Kirmser’s is a brief but pointed memoir of a man, Ricardo J. Brown, who told his naval commander he was homosexual in 1945 and±after surviving a grueling series of interrogation attempting to scare him into naming other names—received a dishonorable discharge.

Besides being about the incipient lesbigay community of my birthplace (in the years before I was born), I was particularly interested in how this instance departs from the conventional wisdom that dishonorably discharged men were too ashamed to return to the heartlands and stayed in port cities such as New York, Los Angeles, and San Francisco, where their concentration produced the “critical mass” of restive homosexuals who started the homophile movement that began to challenge police entrapment and later challenged sodomy laws and discrimination in housing and employment. This seemingly common-sense argument about not going home again was advanced by Alan Bérubé (most visibly in his touching history Coming Out Under Fire). In looking at the life stories of leaders and members of the early American homophile movement, I found that hardly any of them had received dishonorable discharges, and most of them lived in cities before World War II. (I challenged Bérubé’s model in 1984 in my book Social Theory, Homosexual Realities and again in American Gay, published in 1996.)

Brown’s story shows that some of those with the stigma of a dishonorable discharge did go home again. He returned not only to St. Paul but to living with his family. And he found another family of sorts at a drab, working-class, downtown St. Paul tavern run by a German-American couple named Kirmser. There he met a lover, called “Lucky,” another man who also lived with his parents. They were part of a regular crowd that included some lesbian couples.

The danger of being exposed and losing one’s job was clear and present, and paroles after conviction on any morals charge required not associating with other criminals, forcing former patrons to stay away from Kirmser’s. Sodomy is still a crime in my native state, though it also has laws forbidding firing someone because he or she is homosexual.

Brown felt greater solidarity with the frightened fellow denizens of Kirmser’s than did Lucky, who chastised Ricardo for getting involved when two thugs invaded the bar and were beating a nearly defenseless older queen.

Ricardo got to know several Kirmser’s regulars outside the bar, though it remained the main place for him and his gay friends to socialize. He was able to observe some of the strategies lesbians and gay men of the time used to compartmentalize their gay lives, family lives, and work lives, and writes clearly and candidly about his experiences and those of others. Even for someone with whom he socialized outside the bar, “in all the time I knew him, all the nights in Kirmser’s, all of our Saturday afternoons together, all of our talks about books, movies, and music, I never knew where Joe lived, never knew what company he worked for, never knew if he had a family or where he was born” (118).

In school Ricardo had been isolated as the lone Italian (his mother was Italian) in an Irish Catholic school. Although there are many bridges across the Mississippi River, which is not all that immense a body of water bisecting the Twin Cities, Ricardo’s gay and lesbian friends rarely ventured into Minneapolis, though they knew of what they regarded as a “piss-elegant” gathering spot for more sophisticated and more affluent gay people in the larger city across the river. (Yes, yes, I know that some of Minneapolis, including the older part of the University of Minnesota campus, is east of the river… And long before I had any sexual experience, it was Minneapolis I sought to visit whenever I got the chance.)

Brown’s memoir provides insight into the mindset of terrorized homosexuals at the time the McCarthy period was beginning to focus on homosexuals as threats to American security (who were easier to find and expose than were Stalin’s agents). “It was a shame,” he wrote, “that we were as bigoted as anyone else, that our own bitter experiences hadn’t taught us any better lessons in compassion” (63). Although not involved in the early homophile movement, Brown later petitioned for review of his discharge, which was upgraded 36 years afterwards.

I would like to know more about Brown, who died in 1998, having worked for newspapers in Alabama and Alaska, and (one learns from the caption of one of the photos) written a book titled Cold Beer. The book has a foreword from longtime Minnesota State Senator and University of Minnesota history professor Allan Spear that fails to provide the basic information about when Brown wrote the memoir, what his intended audience was, what attempts for publication or provisions for posthumous publication he made, or who supplied the manuscript and family photos. (It also fails to mention other documentation of the era such as Donald Vining’s and Christopher Isherwood’s diaries, or the life history interviews in Growing Up Before Stonewall and some of those in Farm Boys.)

first published by epinions, 18 November 2001

©2001, 2016, Stephen O. Murray