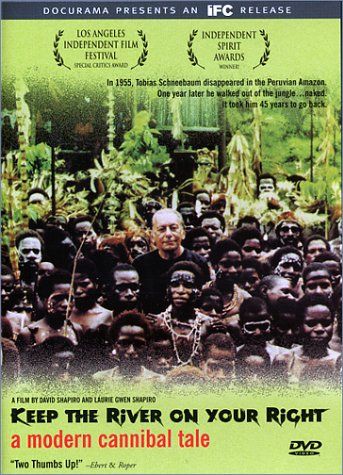

Keep the River on your Right: A Modern Cannibal Tale

Keep the River on your Right: A Modern Cannibal Tale

Written and Directed by David Shapiro and Laurie Gwen Shapiro

Released March 30, 2001

Documentary

93 min.

Review by Stephen O. Murray

April 30 , 2001.

The San Francisco International film festival included an entertaining documentary about a charming “New Age” prophet and fabulist, Tobias Schneebaum.

Trained as a painter by, among others, Rufino Tamayo, Schneebaum began his quest for the wisdom of “primitive” ancients with a Fulbright fellowship to Peru, so that he could visit Macchu Picchu, the mountaintop ruin of an Inca stronghold never found by the Spanish conquistadors.

When I visited Macchu Picchu, its only inhabitant was a llama named Pancho, and Schneebaum wanted to experience life among those living close to nature (as the Incas did not: major subduers of nature, they were far from being a naturvölk).

Hundreds of feet below Macchu Picchu is the Urubamba River, one of the sources of the Amazon. In the mid 1950s, Schneebaum walked downstream along a Peruvian river, the Madre de Dios, keeping the river on his right. He then spent seven or eight months with a Harákmbuet-speaking group that has been called the Amarakaeri.

Schneebaum’s 1969 book Keep the River on Your Right purports to be a record of his stay, which included a completely accepted sexual relationship with an Amarakaeri man and cannibalism following a successful raid on another group. Anthropologists concerned with Upper Amazonia did not take Schneebaum’s wish-fulfillment fantasies seriously. Keep the River on Your Right was not reviewed in the American Anthropologist, and has not been cited by anthropologists as a valid report of an Amazonian culture or plausible conduct of any existing human group. In one of the few reviews in the popular press by an expert on Amazonia, Napoleon Chagnon unequivocally stated, “What he described in this work can only be taken as a highly fictionalized account, a gross and inappropriate vilification.” Since this judgment was reproduced in the 1969 Book Review Digest, it was readily available to anyone made suspicious enough by the unusualness of what Schneebaum “described” (or by the ripeness of his prose) to check whether the book was taken seriously by anthropologists. T. R. Moore, an anthropologist who studied the same group with which Schneebaum stayed, reported:

Keep the River on Your Right is neither an ethnological study nor an accurate factual account, as Schneebaum himself makes clear…. There is no evidence for Amarakaeri cannibalism…. The character Schneebaum calls “Manolo” and reports beheaded and probably cannibalized [in 1956] was living in Ayacucho in the early 1960s. The sleeping arrangements and homosexual practices Schneebaum describes are not part of the Amarakaeri tradition.

Schneebaum himself was careful to note, “There will be no pretense of objectivity here.” Moreover, he added a further disclaimer to the paperback edition: “This book is not an attempt at an anthropological account of a tribe,” and he reiterated the subjectivity of his writing in other publications. No one doubts that he traveled to the wilds of Peru, but it is dangerous to take “I was there” as proof for “Everything I say happened did happen.”

The film records Schneebaum’s return to the Amarakaeri. Nearly 80, hobbled by a recent hip replacement and by Parkinson’s disease, and very conscious of being one fall away from never being able to walk again, Schneebaum is indisputably brave to make the trip (by speedboat). I don’t know of anyone who doubted that he had visited the Amarakaeri. Some Amarakaeri who were young when he visited remember him, and there is much fascination with the photographs he has brought along. These are the first images of olden times and dead ancestors they have seen, since missionaries destroyed all the pictures of naked Amarakaeri that were in the area.

There is no evidence in the movie corroborating Schneebaum’s sexual idyll and his engaging in cannibalism. His “savage” lover is mentioned by no one, including Schneebaum. There is no evidence of the raid or the alleged cannibalism that followed, though the movie’s subtitle includes “cannibal.” There is evidence that Schneebaum knows nothing of the Amarakaeri’s language. He even says he is not good at learning languages (including the New Guinea language of the Asmat with whom he lived off and on for twenty years).

The return to the Upper Amazon is the climax of the movie. It begins with Schneebaum as the local color lecturer on cruise ships plying the waters of Indonesia. There is no evidence of his assisting those whose sexual fantasies of sex with “savages” have been nourished by his writings (Wild Man, Where the Spirits Dwell, for that part of the world), although there is evidence of more metaphorical “pimping” his “primitives.” When he and the film crew go up-river, they find His Asmat mbai (a kind of blood brotherhood involving sex, according to Schneebaum, though whether it may involve sex or whether sex is a usual part of the relationship is unclear in the movie and in Schneebaum’s writings). This man’s affection for Schneebaum is clear. It is also clear that the relationship was not exclusive—that is, that the man has and had sexual relationships with females and males.

Besides following Schneebaum on his cruise ship job, and to revisiting the Asmat and Amarakeari, the film-makers (a brother-sister team) follow Schneebaum around New York, including a gondola-ride interview of a hustler-turned writer (Rick Whitaker) with whom Schneebaum had (/has?) a sexual relationship. The movie also includes footage from a Charlie Rose interview from around 1988, publicizing Where the Spirits Dwell. Mr. Rose does not come off well, and had the movie’s audience laughing at him. More interesting is an appearance two decades earlier on the Mike Douglas show, publicizing the book Keep the River on Your Right, and a very complex, interesting, and touching comment from Norman Mailer, who had been Schneebaum’s neighbor in the early 1950s. Schneebaum makes a number of pithy comments on screen, including one about not understanding what he acknowledges may be a current attempt at primitivism, widespread piercing and tattooing.

Schneebaum is charming in a fairly acerbic New York way. He is modest and uninhibited— and one tough queen. He downplays the role of being a “modern cannibal” and rejects being labeled a “cannibal.” He says that he has forgotten what part of a human body he ate or what it tasted like. It was the violence, which he characterizes as “murder,” that, he says, disturbed him, not eating human flesh.

Nonetheless, what celebrity he has rests primarily on his supposed single venture into cannibalism. He has been on the film festival circuit with the film which epitomizes him as a “modern cannibal.” He wisely says that he never identifies himself as an “anthropologist” (though some time after visiting New Guinea he obtained an M.A. in anthropology to aid his working as a volunteer curator of Asmat art in a museum in Irian Jaya). He also never identified himself as a “cannibal” but is more than complicit in others presenting this as his calling card. (Besides the filmmakers, David Bergman’s introduction to the recent collection of Scheenbaum autobiographical essays, Secret Places.)

The film-makers include about ten seconds of an interview with the most vociferous anthropological skeptic about cannibalism, with no mention of Schneebaum’s claims. There is slightly more from literary historian , Marianna Torgovnick, author of Gone Primitive, in which she says that Schneebaum found what he was looking for (a male sexual partner) in New Guinea. None of the Amazon specialists who have expressed skepticism about Schneebaum’s claims about Amarakaeri valuation of homosexuality or cannibalism appears on screen. (The filmmakers said they shot many hours of interviews with anthropologists, and some surely raised questions about the factuality of Schneebaum’s various claims, but the Shapiros did not allow any critics— particularly of the endeavor on which their own is based—to be included.)

Thus, while the movie is interesting and frequently entertaining, it is in my view less honest than Triumph of the Will, the documentary for which Leni Riefenstahl has been excoriated for two-thirds of a century. Riefenstahl may not have “told the truth” about Hitler, but she was not making a documentary about Hitler. At most, she planned and edited a film celebrating a rally. The Shapiros’ editing strikes me as far more devious. So long as one does not care about truth or balance, both can be enjoyed as skillfully made movies glorifying their subjects. (Except that both were delusional and convinced others to share their delusions and that both were glorified by documentary film-makers, I do not mean to equate Hitler and Schneebaum. It is Riefenstahl and the Shapiro siblings I am comparing: as documentary-film-makers. There are many ways in which I find Schneebaum admirable, including writing much better than Hitler did.)

first published on epinions, 30 April 2001; a shorter version appeared in Anthropology Today

©2001, 2016, Stephen O. Murray