IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

ONE, INCORPORATED, a corporation,

Appellant

vs.

OTTO K. OLESEN, individually and

as Postmaster of the City of Los

Angeles,

Appellee.

No. 15139

[Filed June 13, 1957]

APPELLANT’S OPENING BRIEF

ERIC JULBER

333 S. Beverly Drive

Beverly Hills, California

Attorney for Appellee

No. 15139

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT

ONE, INCORPORATED,

a corporation,

Appellant,

vs.

OTTO K. OLESEN, individually and

as Postmaster of the City of Los

Angeles,

Appellee.

APPELLANT’S OPENING BRIEF

TOPICAL INDEX

Statement of Jurisdiction (Pg. 1)

Statement of the Case (Pg. 3)

Statement of Error (Pg. 4)

Arguments:

- The applicable law is well settled (Pg. 5)

- None of the magazine’s articles is obscene, lewd, lascivious or filthy (Pg. 6)

- The magazine as a while is not obscene, lewd, lascivious or filthy (Pg. 23)

- The post office is depriving appellant of equal protection of the laws, by enforcing against it a literal construction of the statute which it does not enforces against other publishers. (Pg. 27)

- To violate the statute, a work must Be lewdly simulative to the average Reader, and not these of a particular ease. Pg. 31

- A comparison of other literature on The same subject being offered for public sale at the same time as the instant work and freely transmitted in the public mails shows that the instant work is not obscene, lewd or lascivious under prevailing literary standards. (Pg. 33)

Conclusion (Pg. 34)

Appendix (Pg. a)

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CITED

Authorities (Page)

THE AMERICAN LANGUAGE, H. L. Mencken, Supplement I (14)

AMERICAN THESAURUS OF SLANG, Berrey and Van den Bark, 1943 (14)

Burstein v. U.S., 178 Fed. 2d 665 (32)

Consumers Union v. Walker, 145 Fed. 2d 33 (21, 25, 30)

Davis v. U.S., 62 Fed. 2d 472 (21)

DICTIONARY OF AMERICAN SLANG, Crowell, 1934 (13)

Hearings before the Select Committee on Current Pornographic Materials, House of Representatives (28)

Parmellee v. U.S., 113 Fed. 2d 729 (5, 20, 23)

People vs. Creative Age Press, 79 N.Y.S. 2d 427 (18)

PSYCHOLOGY OF WOMEN, Helene Deutsch, Grune and Stratton, 1944 (8)

Sunshine Book Company v. Summerfield, 128 F. S. 564 (23)

Sunshine vs. Summerfield (Court of Appeals, Dist. of Columbia) decided May 31, 1956,_ Fe._ (26)

Swaringen vs. U.S., 161 U.S. 446 (8)

U.S. vs. Bernstein, 178 Fed. 2d 665 (5)

U.S. vs. Dermet, 39 Fed. 2d 564 (5, 20, 22)

U.S. vs. Morten, 282 Fed. 731 (25)

U.S. vs. Kennerly, 209 Fed. 119 (5)

U.S. vs. Levine, 83 Fed. 2d 159 (5)

U.S. vs. Males, 51 Fed. 41 (13)

U.S. vs. Musgrave, 160 Fed. 700 (5)

U.S. vs. One book called “Ulysses”, 72 Fed. 2d 205 (5)

U.S. Code, Title 5, Section 1109 (1)

18 U.S.C.A., Section 1461 (2, 3, 4, 5, 20)

28 U.S.C.A, Section 225 (a) (2)

28 U.S.C.A Section 225 (d) (2)

28 U.S.C.A Section 1339 (1)

Walker v. Popenoe, 149 Fed. 2d 511 (5, 23)

Youngs Rubber v. Lee, 45 Fed. 2d 103 (21)

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

- The statutory provisions believed to sustain The jurisdiction of the District Court are:

- U.S. Code, Title 28 Section 1339, providing that “The District Courts shall have original jurisdiction of any civil section arising under any act of Congress relating to the postal service.”

- U.S. Code, Title 5, Section 1109, providing that “Any person suffering legal wrong because of any agency action, or adversely affected or aggrieved by such action within the meaning of any relevant statute, shall be entitled to judicial review thereof.”

- The existence of jurisdiction is shown by the following allegations of the pleading:

- In the Complaint, (Paragraph II): “At all times herein mentioned defendant Otto K. Olesen was and is the duly appointed, qualified and acting Postmaster of the City of Los Angeles” (Paragraph V); “On or about October 1, 1954, plaintiff…six hundred copies of a magazine…which was called “ONE.” Specifically, the October 1954 issue thereof:” (Paragraph VI): “On October 20, 1954, the defendant Otto K. Olesen…advised plaintiff…that said October 1954 issue of

“ONE” was obscene, lewd, lascivious and filthy…and did thereupon refuse to transmit said copies through the mail and continues to the date to refuse.” - In the Answer, (Paragraph I): “Defendant alleges that the set complained of in the Plaintiff’s Complaint were performed by the Defendant in The exercise of his official duties under authority 18 U.S.C.A. Section. 1461.”

- In the Complaint, (Paragraph II): “At all times herein mentioned defendant Otto K. Olesen was and is the duly appointed, qualified and acting Postmaster of the City of Los Angeles” (Paragraph V); “On or about October 1, 1954, plaintiff…six hundred copies of a magazine…which was called “ONE.” Specifically, the October 1954 issue thereof:” (Paragraph VI): “On October 20, 1954, the defendant Otto K. Olesen…advised plaintiff…that said October 1954 issue of

- The statutory provisions believed to sustain the Jurisdiction of the Court of Appeals are U.S. Code, Section 1291 (U.S.C.A. Section 225(a)) providing that the “court of appeals shall have jurisdiction of appeals from all final decisions of the district courts of the United States…”, and U.S. Code, Section 1294 (U.S.C.A. Section 225(d)) providing that “Appeals form reviewable decisions of the district…court shall be taken…(1) From a district court of the United States to the court of appeals of the circuit embracing the district…”

2.

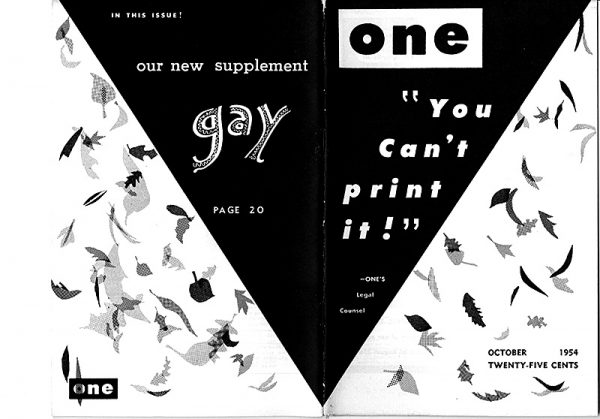

October 1954

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Both Appellant and Appellee have set forth an Agreed Statement as to the facts and issues of the matter (p. 37, Transcript of Record), and we shall not repeat such statement here. There is really only one issue to be decided in this matter, is the October, 1954, issue of “ONE” non-mailable matter under the provisions of the U.S. Code, Title 18, Section 1461, reading:

Every obscene, lewd, lascivious, or filthy book, pamphlet picture, paper, letter, writings, print or other publication of an indecent character and…

Every written or printed card, letter, circular, book, pamphlet, advertisement, or notice of any kind giving information, directly or indirectly, where, or how, or form whom, or by what means any of such mentioned matters, articles, or things may be obtained…

Is declared to be non-mailable matter and shall nor be conveyed in the mails or delivered from any post office by any letter carrier.

3.

SPECIFICATIONS OF ERROR

- The October, 1954, issue of “ONE” is not lewd, lascivious, obscene or filthy, under the standards set forth in 18 U.S.C.A. 1461, and the standards set forth in Paragraph VI of the trail courts Findings of Fact, Conclusions of Law and Judgment, are erroneous as a matter of law and fact.

- That action of the Defendant in refusing to transmit said magazine is arbitrary, capricious and an abuse of discretion, unsupported evidence, deprives Plaintiff of equal protection of the laws and constitutes a deprivation of Plaintiff’s property and liberty without due process of law, and that therefore, the trial court’s Conclusions of Law, specifically Paragraph I thereof, are erroneous as a matter of law and fact.

4.

ARGUMENT

I.

THE APPLICABLE LAW IS WELL SETTLED

It is elementary in constructing 18 U.S.C.A. 1461 that: “The book as a whole must be considered, not isolated passages. It is the “dominant tone’ which controls.” (U.S. v. One book called “Ulysses”, 72 Fed. 2d 705; Walker v. Pepenoe, 149 Fed. 2d, 511; Parnellee v. U.S., 113 Fed. 2d, 729).

“The intent of the author, and his sincerity and honesty, are relevant.” (U.S. v. One book caller “Ulysses”, 5 Fed. 2d, 162; Parnellee v. U.S. supra; U.S. v. Dennet, 39 Fed. 2d, 564.)

“The standard must be the likelihood that the work will do much to arouse the salacity of the reader to whom it is sent as to outweigh any literary, scientific or other merits it may have in that reader’s hand.” (U.S. v. Levine, 83 Fed. 2d, 156.)

The subjective test of the obscenity of the matter is its effect on the average reader, not the exceptional reader. (U.S. v. One book called “Ulysses”. Supra; U.S. v Kennerrly, 209 Fed. 119; U.S. v. Musgrave, 160 Fed. 700; U.S v. One book called “Ulysses”, 72 Fed. 2d, 705; Walker v. Pepenoe, supra; U.S. v. Bernstein, 178 Fed. 2d, 665 (9th C.C.A)).

5.

II.

NONE OF THE MAGAZINE’S ARTICLES IS OBSCENE,

LASCIVIOUS OR FILTHY

1. The cover.

There is nothing provocative about front or back covers.

2. The Statement of Purpose, (page 2).

In view of the fact that the intent and sincerity of the author is relevant, it is respectfully submitted that the statement of publishers’ purpose on page 2 is relevant here. E.G. “homo-sexuality from the scientific, historical and critical point of view…to promote among the general public an interest, knowledge and understanding…to promote the integration into society…” etc.

3. Article entitled “The law of Mailable Material”, (page 4).

Whatever examples are given taken from reported cases, and presented factually, soberly and with dignity. That overall tone is serious.

4. Article entitled “Democracy”, (page 7).

This is a very serious, dignified, and scholarly exposition of the individual’s responsibility in egalitarian society.

6.

5. Article entitled “An Open Letter to You”, (page 10).

This is an article by a contributor to ONE, describing his first personal meeting with the editors. The author speaks of how his preconceived idea of the editors was that of flighty, irresponsible people, but upon personal acquaintance he found them sober, serious, idealistic, and responsible.

6. Fictitious Story entitled “Sappho Remembered”, (page 12).

The best way to analyze this story is to go through it completely and to analyze each quotation which might seem provocative. I will now, however, quote any passages which are obviously without any provocative or suspicious quality.

“He leaped ahead of himself and rushed on. ‘And keep that pianist of yours out of trouble. This town’s hot as a rivet since they picked up the mayor’s kid queening a drag ball. We’re sold out for the next three weeks and we can’t afford any ‘bad publicity.’”

The character speaking here is warning another character to have yet a third party keep out of any soft of homosexual trouble. He assigns as his reason the fact that “the mayor’s kid” was apparently caught as an outstanding homosexual at a homosexual dance. Yet the shock o this statement is only in its blunt reporting on what is purported to be fact. Scandalous charges of this nature

7.

against public officials are not obscene. (see Swearingen v. U.S., 161 U.S. 446).

“Pavia closed the door of their suite behind them, tossed her coat on a chair and gently drew the girl to her. ‘Forgiven?’ she asked at last. She touched the delicate pulse beneath the light golden hair on the child-like temple. ‘Will there ever be a day when you won’t blush when I do that?’ she murmured.”

This is the description of one woman caressing another’s hair, in a tender and moving fashion. There is nothing obscene in the description of the set, and the question then arises whether such a set itself embodied in a story is an obscene set.

It is respectfully submitted that such an episode is not obscene. Countless examples may be found in literature, drama and motion pictures where on woman lovingly caresses another. In “Psychology of Women”, Helene Deutsch, Grune and Stratton, 1944, the classic psycho-analytical text on the subject, that author quotes, in “La Vagabonde”:

“Two women embracing are a melancholy and touching picture of two weaknesses; perhaps they are taking refuge in each other’s arms in order to sleep there,

8.

weep, flee from man who is often wicked, and to taste what is no more desired than any other pleasure, the bitter happiness of feeling similar, insignificant, forgotten.”

There is nothing obscene in such an act, if it is done or described with delicacy.

“Did leah send for other women now that she was a widow?”

This passage asks the simple question, is Leah a lesbian? Such a question is acceptable material in modern literature and is not considered provocative.

“Vividly she remembered their sorority room at the university, the faces of their House Mother and the Dean of Women as the door had burst open upon them, that nightmare of an inquisition in the office downstairs with Leah hysterically screaming accusations at her, her parents’ faces as they had come to take her home. Ten years ago, and yet the agony could still bleed freely. Was it possible she still loved Leah?”

This is a description of an humiliating scene that occurred in the past, and the torment of the character as she thinks back on it. The passage cannot be said to arouse sexual

9.

desire; on the contrary, the scene described is on of anxiety and shame. Descriptions of such scenes are also common and accepted in modern literature.

“Pavia’s mind could not leave her hotel suite, where the girl she loved above all else was waiting for a fatal call.”

The statement what a woman loves another woman above all else is not, per se, obscene. While the description of homosexual acts between women, spelled out in detail, could conceivably be considered obscene, a mere statement that one woman “loves” another is innocent. Innumerable references to love between man and man and woman and woman are to be found in literature from the Bible to present day.

“Can’t we try just once more, darling.”

One character had here asked another to resume homosexual relations that were broken off long in the past, the other refuses. Here again, if there were a detailed description of homosexual acts or the preliminaries thereto between two women, such descriptions might be considered obscene, but the more request of the to the other e said to have that effect.

10.

“After that, even a fool would have understood that Leah didn’t care where her pleasures came from — so long as the supply was tremendous, varied and unending. Pavia went back to town in a cab, leaving Leah’s paramour to justify his deliberate intrusion in ways best known to them alone. She hoped they would be very happy, as she laughed in spite of her misery.”

This is description of a character as unprincipled, undignified, and promiscuous. Such a description, which does not go into details, cannot be said to be so provocative to the reader as to stimulate sexual desire. The passage also implies that after Pavia’s departure, Leah and her paramour made love, but this is only an implication and is, again, very, very common in modern literature.

“Drunk or sober, I don’t love him … like I do you!” She started to cry. “Mrs. Brake may be more important to you than I am — but she won’t go with you everywhere as I will and you do need me … In spite of what you may think … as I need you!”

This is a declaration of love by one woman for another. Here again, it is respectfully submitted that a mere declaration of love can never be considered obscene, per se, if not accompanied by enough description of acts between the characters as to become physically arousing to the reader.

11.

Compare such a declaration, for example, unaccompanied by any description of acts, with the detailed, explicit, and frequent episodes that occur in ninety-five percent of modern fiction, in which the love of men and women is described in terms not only spiritual, as the case here, but also in graphic physical terms.

First, Mrs, Brake is sleeping with her chauffeur, and I’m glad she is.

This is merely a statement that one character is having an affair with another. This is perfectly innocent by today’s literary standards.

We have taken the story “Sappho Remembered”, passage by passage, and analyzed each description in this story which might be considered “obscene.” It will be evident that when considered in this manner, and even considered as a whole, the story deals only in the spiritual affection between women, and their personal difficulties in adjusting their personalities to these feelings. It is a story of a struggle within the personality. It is a psychological story. There are few, if any, physical elements in it. What conflict there is exists in the minds of the characters. It is respectfully submitted that there is nowhere in this story enough physical elements or sexual provocation as to even remotely arouse the sexual salacity of “the average reader.”

12.

7. News Excerpts about Miami, (page 16).

These are experts from Miami newspapers. Every word which appears therein is taken from local Florida newspapers.

8. Poem entitled “Lord Samuel and Lord Montagu”, (page 18).

This is satiric and burlesque poem, taking as it’s theme the recent “scandal” in England concerning the prevalence of homosexuality in that country, and commenting satirically upon a statement these passages of the poem which might be suspected of being “obscene.”

Lord Samuel is a legal peer

(while real are Monty’s curls!)

Some peers are seers and some are queers—

And some boys WILL be girls.

This is a comic statement that “some peers are queers, and some boys are girls.” This is merely a statement that among English nobility, one finds homosexuality, a premise which is now receiving much publicity in other magazines. The word “queer” is in common and ordinary usage. It is classed by authorities as slang, not obscenity. (See Dictionary of American Slang, p. 32, Crowell, 1934: “Queer: effeminate.” It is used in modern books (see From Here to Eternity) without any known repercussions. Mere vulgarity does not come within the purview of the obscenity statutes (U.S. v. Males, 514 Fed. 41).

13.

Would he idly waste his breath

In sniffing round the drains

Had he known ‘King Elizabeth’

Or roistering ‘Queen James’?

Here the post asks if Lord Samuel would be so intolerant if he were more familiar with English history, which includes a number of noted homosexuals. The phrase “Sniffing round the drains” is merely poetic exaggeration to burlesque and ridicule the Lord in his investigations of public restrooms. This is not obscene or filthy, by merely dramatic emphasis to make a point; much rougher references can be found in Shakespeare and other accepted and beloved authors.

They say the sins of Sodom

In these Isles have come to roost —

So if you’re flying east over GANDER

Watch your don’t get fairy “goosed.”

The purport of this rhyme is that there are so many homosexuals in England that a traveler approaching the island by way of the airport, Gander, must take precaution against liberties perpetrated on his person. The word “goosed” is defined as “to tickle the posterior in order to cause one to jump” (American Thesaurus of Slang, Berrey and Van den Bark, 1943, p. 161). This word is discussed at length by the noted student of language, H.L. Menken, in his great work The American Language. Supplement I, p. 390 through 392, as follows:

14.

One of the most mysterious American verbs is to goose. Its meaning is known to every schoolboy, but the dictionaries do not list it, and so far as I know no lexicographer has ever worked out its etymology. The corresponding adjective, goosey, was noted in American Speech in 1933 as moaning ‘nervous touchy,’ and the diligent Bolinger has recorded that to goose itself has been taken over by truck-drivers and aviators to signify feeding gasoline to an engine in irregular spurts, not beyond this the philological literature is a blank. The preponderances of medical opinion, I find, inclines to the theory that the verb was suggested by the fact that geese, which are pugnacious birds, sometimes attack human beings, and especially children, by biting them at their fundaments. There is also the possibility that the term may be derived from the old custom of examining a goose before turning it out to feed in the fields by feeling of its rear parts: if an egg could be felt it was kept in its pen for a day. This method of exploration is still used by some housewives in order to estimate the fatness of a dressed goose. The question remains why one person is goosey and another is not. Some resent goosing not more than they resent a touch on the arm, whereas others leap into the air, emit loud cries, and are thrown into a panic. One of my medical informants suggests that susceptibility is mainly psychic, and may have its origin in an obscure fear (and perhaps an infantile memory) of a sexual attack, but other authorities believe that it is caused by physical sensitiveness and is

15.

psychic only by association. Meanwhile, every American knows what to goose means, though the term appears to be unknown in England, and there are no analogues in the other European languages. The practice is the source of many serious accidents in industry and the National Safety Council has issued a number of posters warning against its dangerous and sometimes even fatal consequence.(3) It is also frowned upon by the various state industrial accident commissions,(4) and by the Army and Navy.

(3) One of them reads: ‘Goosey. A goosey man is one who is nervous. When you touch him he jumps. One goosey man jumped off a scaffold and broke both legs when a fellow worked touched him. Another almost jumped into a pot of molten slag. To intentionally startle a nervous person while at work is more than a mean trick — IT IS CRIMINAL.’

(4) It is denounced, for example, along with horseplay and scuffling, on p. B of General Safety Manual Applicable to All Hazardous Industries, issued by the State Industrial Accident Commission of Oregon, Jan. 1, 1937. I am indebted here to Mr. Robert W. Evenden, director of the commission.”

16.

This word, therefore, can be considered as on in common usage and associated with prank and surprise, rather than obscenity.

And if you wish to Pick a Dilly

When you’re strolling out at night,

Just make sure it’s not a “Lily”

Or a male transvestite.

The reference to “Pick a Dilly” is a play on words on the name of the section in London most famous who would “pick up” such a girl to make sure that she is in fact a girl. This is a use of exaggerative humor, the post implying that things have reached such a terrible pass in England the observer cannot tell who is a genuine woman and who is a male passing as a woman. This suggestion is comic. While this is a observation about sexuality in England, it no more arouses sexual feeling than would similar, widely published, comments in recent years about women’s short hair cuts or women’s masculine fashions, in which it was also pointed our that you can’t tell a man from a woman.

For there’s blackmail in the woodpile

And there’s blackmail by the fence,

But to black male and to white male

It’s: AVOID PUBLIC “GENTS”!

17.

The post here makes the comment that he would advise all males to avoid frequenting public restrooms. This is, obviously, because public restrooms have featured notoriously in the current English vice scandal. This is an admonition not calculated to arouse sexual desire.

Taking the poem as a whole, it can be said that the poem is broad slapstick satire of social conditions in England now receiving a great of publicity.

In this instance the language of the New York court in People v. Creative Age Press. 79 N.Y. Supp. 2d, 427 (1948), may be of value. In that case the court said of a literary work

Their language is course and vulgar. They make occasional references to sexual contacts that are sophomoric and nasty. These references are, however, wholly incidental and are not descriptive. They are minor phrases and sentences serving in aid of characterization. Such incidental language does not of their itself bring a literary work within the terms of the statute.

9. Collection of Cartoons entitled “The Gay Menagerie”, (page 20).

This is a collection of cartoons of animals. Each animal is drawn ina slightly exaggerated fashion, to accentuate the quality for which the animal is best known. For instance, a

18.

rabbit is drawn as a particularly timid rabbit; a wolf as a particularly aggressive and lecherous wolf; a lion as extremely rough and husky; a monkey as particularly shrewd and intellectual. Each animal is supposed also to represent a particular type of human being, and in the content in which they appear, it is clear that each cartoon is supposed to satirize a particular type of homosexual, i.e., the timid and retiring , the lecherous, the extreme intellectual.

The pictures themselves are completely inoffensive and the captions are likewise from any obscenity in themselves, for example, “Excuse me, I see a friend at another table,” or “Anybody want to go for a motorcycle ride?”

The only feature of these cartoons that anyone might find objectionable would be a sort of implied acceptance of the fact that homosexuals exist, and that there are various types among them, and that these types can be characterized and satirized as can other types of human beings. This goes no further than to say, however, that homosexuals are people, that they exist, that they have definite personalities, and that they can be depicted in drawings as well as in prose or poetry. That homosexuals may thus be in fact depicted, if done without deception of their acts, is, I believe, clear. I have never seen it suggested by any authority that homosexuals cannot be depicted in art.

10. Letters to the Editors, (page 26).

There is nothing objectionable in these letters, but I

19.

urge that they be read and read carefully. It is evident that their outstanding quality is the sincere appreciation of those who read the magazine. They all stress one thing: that the magazine helps them to understand themselves, and is helping society to understand them. Since “the purpose, sincerity and honesty of a publisher are always relevant in a question of obscenity” (Parnellee v. U.S., supra: U.S. v. Denett, supra), it is respectfully submitted that these letters to the editors, unsolicited and printed without editing, represent in fact a powerful evidence that the magazine in fact does not arouse the salacity or sexual desires of readers, but, in fact, aids their understanding of themselves and by society.

11. Advertisements.

On pages 29 and 30, there appear advertisement of “Foreign books andmagazines” and information as to where they may be obtained. The Post Office contends that some of these are obscene, and that therefore, ONE has transgressed that portion of 18 U.S.C.A. 1461 which makes criminal “Every … advertisement … giving information, directly or indirectly, where, or how, or from whom … such mentioned matters, articles or things may be obtained … ”

It is Plaintiff’s position, first, that the magazines and books advertised are not obscene. They were thoroughly “screened” by ONE’s legal counsel before being permitted to advertise. (See the affidavit or Eric Julber, Esq., filed herewith). There has never been any judicial determination known to

20.

this writer as to the mailability or non-mailability of any of these works. It is respectfully submitted that in the absence of such a judicial determination, any charge of “obscenity” is purely opinion, and not even admissible as evidence.

Plaintiff’s counsel, however, screened only “sample copies” of each of the magazines. It is, of course, possible that, unknown to Plaintiff, some subsequent issues of a particular magazine might contain objectionable material. Or it is even possible that the foreign advertiser might conceivably (certainly without Plaintiff’s knowledge) communicate personally with one of these readers answering the ad, and proceeds to communicate obscene proposals.

But, Plaintiff contends, Plaintiff cannot thus be held guilty of the act of another unless he knew or had reason to know of the intention of the advertiser, or knew or had reason to know of the obscene character of the matter advertised.

There are two aspects to Plaintiff’s argument; (1) The statute cannot be read literally, and (2) if it is to be read literally, then it must be enforced against all publishers without discrimination.

(1) The courts have traditionally refused to interpret this statute literally.

See the long line of “contraceptive” cases (Consumers Union v. Walker, 145 Fed. 2d, 33; Young Rubber v. Lee, 45 Fed. 2d, 103; Davis v. U.S., 62 Fed. 2d, 472) in which the courts have consistently had to read “reasonable exceptions” into the statute to avoid and absurd (or unconstitutional) result.

21.

In Consumers Union v. Walker, the court says:

“All laws should receive a sensible construction … it will always, therefore, to be presumed that the legislature intend exception to its language, which would avoid results of this character. The reason of the law in such cases should prevail over its letter.”

The court goes on to find that, even though the statute clearly forbids “every” writing about contraception, “Congress did not intend to exclude from the mails properly prepared information intended for properly qualified people.”

So, too, the language of this same statute which deals with advertisements must be given a reasonable construction, and it be presumed that the legislature “intended exceptions to its language.” For it would be a deprivation of due process of law to make a publisher responsible for the act of another over whom he had no control or authority, and to whom he had merely leased advertising space, after taking reasonable precautions to ascertain the advertiser’s good faith.

The case of U.S. v. Horton, 262 Fed. 731, is squarely in point. In that case, the defendant was charged with violation of the Prohibition Act, which forbids possession of “any liquor or property designed for the manufacturing of liquor intended for use in violating this article.” The court said:

“The statute is not intended to include and make criminal a possession which is not conscious and willing

22.

… it is clear the intent of neither the designer nor of the maker could be imputed to the possessor.”

In U.S. v. Dennet, 39 Fed. 2d, 564,563, the court says:

“The statute we have to construct was never thought to bar from the mails everything which might stimulate sex impulse. If so, much chaste poetry and fiction, as well as many useful medical works would be under the ban. Like everything else, this law must be constructed reasonably with a view to the general objects aimed at. While there can be no doubt about its constitutionality, it must not be assumed to have been designed to interfere with serious instruction regarding sex matters unless the terms in which the information is conveyed are clearly indecent.”

A literal interpretation of the statute would make the publishing business an utterly impossible one. It is common knowledge that the bulk of magazine revenue comes from the sale of space to advertisers. The publisher should, of course, exercise reasonable care to screen advertisers. But how can he know what may hide behind an innocent façade? We have all seen ads in respectable magazine for “studies for art lovers,” and “adult stories.” Can the publisher be held to an insurer’s standards, so far as the Post Office is concerned? The answer is obviously: No.

23.

(2) The other aspect of Plaintiff’s argument is that the Post Office has not attempted to hold any other publisher but ONE to such an insurer’s standard, and has singled out ONE unfairly, and has sought to apply against it a literal construction which it does not enforce against other publishers. (See ARGUMENT IV., infra).

III.

THE MAGAZINE AS A WHOLE IS NOR OBSCENE, LEWD,

LASCIVIOUS OR FILTHY.

It is established law that the entire publication must be considered, not merely portions thereof. (Parnellee v. U.S., supra; Walker v. Popenoe, supra). The dominate tone of the work is the controlling factor; incidental stimulation is irrelevant. (Walker v. Popenoe, supra).

In Sunshine Book Company v. Summerfield, 128 F.S., 564, the trial court summarized the existing law on the subject, saying: (p. 568)

“Second, ‘The statute does not bar from the mails an obscene phrase or an obscene sentence. It bars an obscene ‘book, pamphlet … or other publication….’ If a publication as a whole is not stimulating to the senses of the ordinary reader, it is not within the statute.’

“Third, ‘It would make nonsense of the statute to hold

24.

that it covers works of value and repute merely because their incidental effects may include some a light stimulation of the senses of the ordinary reader. The dominant effect of an entire publication determines its character.’

“As was pointed out in the case of Parnellee v. United States, 72 App.D.C. 203, 113 F. 24 729, the modern rule was restated with emphasis, and 113 F. 24 at page 731 the Court said, and this trial court quotes:

“‘But more recently this standard has been repudiated, and for it has been substituted the test that a book must be considered as a whole, in its effect, not upon any particular class, but upon all those whom it is likely to reach.’”

A reading of the entire magazine shows that the magazine as a whole is serious, responsible and sincere. It is true that its serious articles are balanced by fiction and humor, but it is obvious that the serious articles are not merely “widow dressing.” “The Law of Mailable Material” explains to the layman in very serious fashion a very technical body of law. The article on “Democracy” is so uncompromising, demanding and intellectual, it could only appear in a magazine of the highest ideals and principles.

The dominant tone of the magazine is one of sincerity. It is an attempt to grapple with a social problem of the deepest

25.

order in terms comprehensible and palatable to laymen. It strives to create understanding of an extremely knotty social problem.

Yet an examination of the District Court’s opinion clearly shows that his findings of fact and conclusion of law are based, not on the magazine as a whole, but on three isolated excerpts taken out of context.

In a recent case decided by the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia, Sunshine v. Summerfield, — Fed. 2d — decided May 31, 1956, the court deals with a precisely identical situation, and says:

“The Examiner of the Post Office Department and the District Court explicitly recognizes in the opinions that the publications must be considered in their as a whole. Yet an examination of their opinions, as well as of the Solicitor of the Post Office Department, shows no effort to weigh the material considered objectionable against the rest of the contents, or to weigh the risk in permitting the former to circulate in halting circulation of the latter. Furthermore, neither the Department nor the District Court appears to have investigated or considered the intent of the publisher, one of the important elements in obscenity cases. Parnellee v. United States, supra, 72 App, D.C. at 209, 113 F. 2d at 735; United States v. One Book Entitled

26.

Ulysess, supra, 72 F. 2d at 707, 708. ‘Honest, sincere’ works must be distinguished from publications ‘wholly for the purpose of profitably pandering to the lewd and lascivious.’ Parnellee v. United States, supra, 72 App. D.C. at 209, 210, 113 F. 2d at 735, 736. If the matter of intent had been considered, substantial evidence of sincerity of motive, and lack of ‘profitable pandering,’ was contained in uncontroverted affidavits by the managing editor of the magazine in question, who is an ordained Baptist minister, and by the editor of the magazine, his daughter.”

It is clear from reading of the District Court’s opinion in this case, also, that the District Judge did not take into account at all the motives or intent of the publishers of ONE.

IV.THE POST OFFICE IS DEPRIVING APPELLANT OF EQUAL

PROTECTION OF THE LAWS, BY ENFORCING AGAINST IT

A LITERAL CONSTRUCTION OF THE STATUTE WHICH IT

DOES NOT ENFORCE AGAINST OTHER PUBLISHERS.

Appellant has previously contented that the portion of the statute dealing with “advertisements’ must be read and interpreted so as to allow for “reasonably exceptions” (Section II, ARGUMENT, subsection 11). Yet the Post Office has been adamant in enforcing against the appellant a literal interpretation that

27.

would make even an innocent leasing of space by a publisher to a lessee who subsequently, unknown to the publisher, attempted to peddle pornography, a violation of statute. The trial court also adopted such a literal interpretation, by disregarding the effect of appellant’s uncontroverted affidavits, which show good faith and lack of knowledge on the part of the publisher.

A diligent search of the legal reports has shown no reported case in which such a literal construction has been enforced against any other publisher except, ONE, INCORPORATED. As a matter of fact, the Post Office had never, even out of court, sought to enforce such a construction.

In “Hearings Before the Select Committee on Current Pornographic Materials, House of Representative,” December 1 through 5, 1952, representatives of the Post Office testified before a Congressional Committee on their procedure in enforcing the obscenity statute against “advertisers.” The following extract is from testimony by Michael L. Keefe, Director of Mail Fraud Investigations, and Harry J. Simon, Inspector:

“Mr. Keefe: Within the Bureau itself we have one particular section that deals with nothing but the unmailable matter, which includes this obscenity … with respect to the starting of an investigation, there are many times when it is based upon complaints coming in from the public. In other cases, more particularly in Mr. Simon’s work, it is the scanning of magazines, the ads.

Some of them apparently are very innocuous at first, and you have to dig for them because they generally

28.

represent the real bad stuff, and they don’t advertise it publicly, and people don’t complain about it because ordinarily the deal is with the person who purchases material and he does not complain. He got what he wanted, so we have to dig for those to see whether the mails are being used improperly.

Mr. Burbon: Such advertisements are usually disguised to a certain extent as to their real meaning, is that so?

Mr. Keefe: Yes, it might be so. It might be such things as the confidential developing of films, pin-up pictures, and after you deal a little while and gain the man’s confidence, he keeps giving you more and more, and sometimes it seems there is no end. Each offer may be a little stronger than the other, but ordinarily they will not come out in the open at first with that kind of material … Insofar as the investigation part of it is concerned, as I say, Mr. Simon and another inspector subscribe to a number of magazines, and they purchase a number of magazines from the newsstands, and anything that seems current or a good source for these materials, they have clerks to pick those ads out, and from that point on Mr. Simon and the other inspector will pick out and see what happens in connection with it …

Mr. Simon: If we see an advertisement that appears suspicious we will issue a case for investigation, and undertake what is known as test correspondence.

We have approximately, oh, several hundred

29.

names, I would say, fictitious names, that we use in the investigation of cases of this kind, and will order the various items that they offer for sale … and we build up the case to a point where we have sufficient evidence to present to the United States attorney or if we feel from our past experience that the United States attorney will not authorize prosecution we will refer the case to the Solicitor for an unlawful order.”

Note that Post Office officials speak only about action against the advertiser, and there is no mention whatsoever or action — taken, contemplated, intended or even hoped-for — against any publisher who merely leases space without knowledge of the lessee’s intent. In these comprehensive hearings, the Post Office had ample opportunity to request such power, if it were even desired, but in the entire transcript (387 pages) there is not a mention of such action ever having been taken.

The unique application of literal construction of the statute against the appellant, therefore, is obvious and errant discrimination. See Consumers Union v. Walker, supra, where the court says:

“In the Government’s brief, it is urged by way of excuse for no action having been taken against Fortune Magazine, Readers Digest or the American Medical Journal, that this was probably the result of oversight that no benefit can be claimed in favor of the pamphlet issued by

30.

appellant merely because the Postmaster General has neglected to proceed in other cases. This is not a persuasive argument. The other magazines are of wide circulation … They have been called to attention of the Postmaster General much more quickly than would this little pamphlet … Whether intended of not, the result of the action taken in the present case constituted a clear discrimination against appellant’s pamphlet in favor of the others.”

V.

TO VIOLATE THE STATUE, A WORK MUST BE

LEWDLY STIMULATIVE TO THE AVERAGE READER,

AND NOT THOSE OF A PARTICULAR CLASS.

In his findings of fact, the trial Judge stated that (Finding, paragraph VI, sub. 1) “The story “Sappho Remembered” is obscene because lustfully stimulating to the homosexual reader.”

This statement indicated that the Trial Court used an incorrect standard in arriving at his decision. The proper test is not the effect of the work on the exceptional reader, but rather, on the average reader. In Parnellee v. United States (supra), it is stated:

31.

“But more recently this standard (Regina v. Hicklin) has been repudiated, and for it has been substituted the test that a book must be considered as a whole, in its effect, not upon any particular class, but upon all those whom it is likely to reach. (Citations.)”

And this language can be considered as properly stating the rule in the Ninth Circuit, for, in Burstein v. United States, 178 Fed. 2d, it is said:

“In this case the trial court did not fall into any of the errors commented upon in the cases to which reference has been made. It did not point to a particular class of persons especially susceptible to immoral influences; rather the instruction referred to the ‘common sense of decency and modesty of the community.’ (Emphasis supplied.) The instruction later given referred to ‘that form of indecency which is calculated to promote the general corruption of morals. (Emphasis supplied.) Nor did the instruction permit the jury to judge the book by detached portions or otherwise than as a whole.”

32.

VI.

A COMPARISON OF OTHER LITERATURE ON

THE SAME SUBJECT BEING OFFERED FOR PUBLIC SALE

AT THE SAME TIME AS THE INSTANT WORK

AND FREELY TRANSMITTED IN THE PUBLIC MAILS

SHOWS THAT THE INSTANT WORK IS NOT OBSCENE,

LEWD, LASCIVIOUS UNDER PREVAILING

LITERARY STANDARDS.

Appellant has appended to this Brief, an Appendix, in which are set forth excerpts taken from books and magazines which were offered for public sale and reading at book stores, drug stores, newsstands and public libraries at or about the same time as the Postmaster refused to transmit the October, 1954, issue of “ONE”. These excerpts all deal with the same subject matter as is dealt with in the instant work, to wit, homosexuality.

The writer knows of no official action being taken by the postal authorities to declare any of the magazines or works quoted from to be “non-mailable.”

The fact that these books and magazines are offered for public sale — and even carried in our public libraries — and some of which have the status of minor classics, indicates that, under current prevailing standards of public and literary morality, the matter contained in the October, 1954, issue of “ONE”

33.

is far from being “obscene,” and in fact, is innocent and inoffensive.

CONCLUSION

It is respectfully submitted that the judgment in this matter should be reversed, with a specific finding that as a matter of law, the October, 1954, issue of “ONE” is mailable matter, entitled to the full privileges of the United States mails.

Respectfully Submitted,

ERIC JULBER,

Attorney for Appellant.

34.