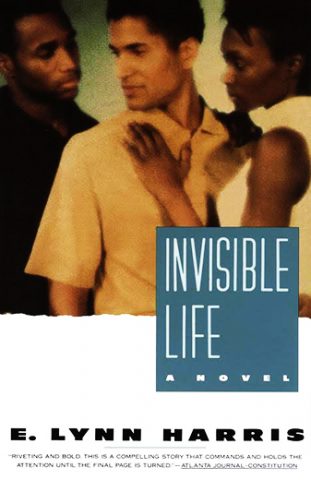

Invisible Life

Invisible Life

by E. Lynn Harris

Published by Consortium Press

First published 1991

Anchor Reprint edition: February 14, 1994

Doubleday 5th Anniversary edition: March 16, 1999)

Fiction (subgenre)

272 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

February 23, 1997.

I do not find any of the characters in E. Lynn Harris’s popular (60k+ sales) first novel, Invisible Life, of black gay and bisexual characters particularly believable. Who does what to whom (in the male-male relations) is unspecified (unlike in the male-female ones). It’s like the movies in which neither man goes down, bends over, or raises his legs for penetration. I find it hard to believe that three masculine adult black men are satisfied without penetrative sex.

I read the passage that comes closest to addressing this to mean that neither Quinn nor Raymond fucks the other:

Although we didn’t play roles, it was apparent that we both were used to being in charge. In previous relationships with men, I had always held back, never giving myself totally. AIDS had a lot to do with that, but in many ways it became a man thing with me. (p. 219)

He registers that heterosexual oral sex had become accepted (“I found it interesting that oral sex was no longer taboo in the black community, as it once had been… There was a time when black men never admitted to oral sex, but now they bragged about it. It was thought that only weak men or sissies would participate in such an act” (p. 210).

For someone who grew up among whites with mostly white friends (“My high school was predominantly white and so were most of my friends. I went to school with whites, played sports and worked with whites. The only things I didn’t do with them were go to church and go to bed” (p. 183)), the absence of any important adult relationships with whites is surprising.

And for someone who considers it a lifestyle, not a life (p. 168; and “being gay was such a small part of who I was,” p. 205), Ray is very judgmental about other black men who seek to have sex with men but do not consider themselves gay (Kelvin who brought him out, and the pro football player Basil who comes on to him). And also of “leaders in the black community would have had you believe that you couldn’t be a service to the community and gay too. They viewed black homosexuals as freaks of nature and felt their career options should be limited to hairdressers and interior decorators” (p. 220). That is, he demands open acceptance from others while hiding himself (not unparalleled, of course!). His best openly gay friend, Kyle, is more laissez-faire: “Chile, if you want to live a confused life, then more power to you” (p. 176).

Whether Kelvin is HIV+ and infected Candace, who dies of pneumocystis the day after their hospital wedding, is not definite. But emotionally, and in terms of disease(s), these bisexual men are a menace to the women who give them respectability (and love, innocent of full knowledge of what their male partners do or have done elsewhere).

Harris, who was born in Flint, Michigan in 1955, died in LA in 2009. He had published a memoir, What Becomes of the Brokenhearted? in 2003.

Invisible Life was initially self-published in 1991 and mass marketed by Anchor in 1994.

23 February 1997

©1997, 2016, Stephen O. Murray