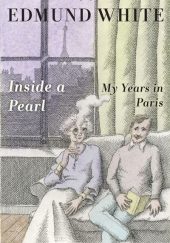

Inside a Pearl: My Years in Paris

Inside a Pearl: My Years in Paris

by Edmund White

Published by Bloomsbury

First published February 27, 2014

Genre (subgenre)

272 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

March 21, 2015.

Anywhere except in the Princeton University English Department (which also houses Joyce Carol Oates), Edmund White would seem hyper-prolific.

I own 24 of the 25 books listed as “by the same author” at the front of Inside a Pearl: My Years in Paris, including his previous memoir (arranged topically rather than chronologically), My Lives, and City Boy, as well as two earlier books on his life in Paris: The Flaneur and Our Paris. [1]The latter illustrated by Hubert Sorin, his lover, whose demise is agonizingly detailed in The Married Man, which purports to be a novel though it seems even less fictionalized than A Boy’s Own … Continue reading

With occasional invocations of Texas and Ohio roots, Inside a Pearl begins with the 43-year-old novelist, flush with some commercial success from A Boy’s Own Story and hoping to escape the pervasive angst of the AIDS epidemic in gay Manhattan, arriving in Paris in 1983 with a $16,000 Guggenheim Fellowship and very little ability to understand spoken French.

He had the great fortune to be befriended by Marie-Claude de Brunhoff who, among other things, was a book scout for an American publisher and was acquainted with most everyone who was anyone in French letters. Though often seeming garrulous anecdotage (something of a prerogative for a 74 year old), White’s affections for and social debts to Marie-Claude run through the book, and the understated account of her death is one of its most moving segments. Marie-Claude has something of the place/function of Marie-Laure, Vicomtesse de Noailles, in Ned Rorem’s Paris Diary, if lacking so grand a title. Of course, White knows Rorem and remarks on Rorem’s return every decade or so to confirm that Paris is not what it used to be (when Rorem was young and sought after for his beauty).

White is leagues apart from the narcissism of the young Rorem, though enjoying narcissism in young men cruising the Tuileries gardens or bathhouses of Paris and eager to cater to presentations of macho selves (at least in being a bottom, White follows Rorem’s pattern, with considerably more graphic details!).

White is a good storyteller, though I often do not see the connection between adjacent stories. I would not go quite so far as to say the book free-associates, but the stories certainly are not knit together. Marie-Claire is something of a warp (in weaving terms), but the whole seems more a crazy quilt than a tapestry.

It also frequently breaks away from the subtitular “Years in Paris.” For me, the most interesting chapter discusses various English writers White met staying in London, including Bruce Chatwin (with whom he had sex immediately upon meeting), Julian Barnes, Martin Amis (whom he vigorously defends), Alan Hollinghurst, Adam Mars-Jones (with whom he did a collection of AIDS stories, The Darker Proof, in 1988), and Salman Rushdie (about whom he has nothing interesting to add).

White produces extended comparisons of French (Parisian) and English (Londoner) national character and culture. There are also sojourns to Mexico, Morocco, Provence, and Providence, Rhode Island. (White returned to the U.S. to teach first at Brown, taking Hubert Sorin along for a difficult year there).

The rejection by White’s usual admirers (notably Susan Sontag who was outraged at the character somewhat based on her in it) of Caracole (1985), his highly mannered novel (the first he wrote while living in Paris), continues to bother him on the evidence of multiple comments in Inside a Pearl. [2]Édouard Roditi (1910–1992) warned him not to try such a book again unless he wanted to destroy his career, and White took up the autobiographical saga of A Boy’s Own Story (1982) with The … Continue reading

White briefly recalls Michel Foucault (about whom he wrote a fawning article “The Emperor of the Mind” once upon a time), Alain Robbe-Grillet (and his sadist wife), Julia Kristeva (and her husband Philippe Sollers), Mavis Gallant, and James Lord; mentions Milan Kundera, Michel Houellebecq, Guy Hocquenghem, and Michel Tournier (without giving any indication of having ever met). He does not mention Marguerite Duras, Yves Navarre, Hervé Guibert, Jacques Derrida, or Jacques Lacan (he disposed of Lacan in My Lives with unusual vehemence—even greater than his annoyances with Germaine Greer).

There are also sketches of many persons of whom this reader has never heard, including many of White’s many sex partners. Some of these are vivid enough that it does not matter that the reader has no previous interest. I would not exonerate the book from the charge of “name-dropping,” but there is more than that, including steady (relentless even!) self-deprecation. And the mystery of when and how White wrote so much remains unsolved!

Numb after Marie-Claude’s death, White enumerates what he is “alive in order to [do]—to teach, to trick, to write, to memorialize, to be a faithful scribe, to record the loss of my dead.” That seems to me to be a lot, and White seems to have succeeding (and be again succeeding in this 26th book) at fulfilling these duties.

©2015 by Stephen O. Murray. All rights reserved.

This review was first published by Out In Jersey magazine.