The Hours

The Hours

by Michael Cunningham

Published by Turtleback Books

Published November 1, 1999

Fiction

299 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

May 12, 2002.

Although I greatly admired and was moved by Michael Cunningham’s first novel, A Home at the End of the World, I was put off by the length, the title, and by the cover of his second, the roman fleuve Flesh and Blood. And I was slow to pick up The Hours. Being crowned with a Pulitzer Prize did not encourage me (though last year’s prize committee’s pick of Michael Chabon made the Pulitzer seem more of an inducement than a warning).

Did I want to read a novel in which Virginia Woolf, writing Mrs. Dalloway in 1923 rural England, is intercut with Mrs. Dalloway preparing to throw a party? And with a story of a woman (Laura Brown) reading the novel in 1949 Los Angeles while her momma’s-boy son helps her make a cake for her husband’s birthday party? And with a present-day story in which one character (Richard) calls another (whose first name is Clarissa) “Mrs. Dalloway,” and she is also planning a party (in late-1990s Manhattan) for him?

The ripples from Virginia Wolf sounded so schematic. And starting the book with Wolf’s (1941) suicide seemed very heavy-handed when I finally picked up the book to read.

However, I read on and was surprised to learn that I really did want to read a novel about Virginia Wolf writing Mrs. Dalloway, etc. For one thing, Cunningham is a superb prose stylist, invoking sense perceptions with beautifully precise ways. A reviewer should not reveal what the eventual payoff of the Wolf/Mrs. Dalloway resonances is, but not only is there one, but even the shadow cast by Wolf’s suicide note and drowning herself is justified (and that is not an easy task to set oneself!).

To be able to read Mrs. Dalloway, Mrs. Brown has to check into a hotel, so The Hours is particularly good hotel reading, making one feel lucky to have a place to read and to regard hotels as refuges for readers. Though I think that reading the novel in a hotel augments its pleasures, there are plenty of pleasures in it for reading in other locations. The structure quickly becomes seductive.

To be able to read Mrs. Dalloway, Mrs. Brown has to check into a hotel, so The Hours is particularly good hotel reading, making one feel lucky to have a place to read and to regard hotels as refuges for readers. Though I think that reading the novel in a hotel augments its pleasures, there are plenty of pleasures in it for reading in other locations. The structure quickly becomes seductive.

I also found many of the characters moving, especially Louis, who had been the isolated point of a mid-1960s attempt at a “free love” triangle with Richard and Clarissa, and Clarissa’s concern for Richard (who is dying of AIDS and about to receive a prize for his lifework, the most celebrated part of which is about Clarissa).

Although I think that Virginia Woolf would be pleased by the homage of making her novel so central to another more than three-quarters of a century later, I can sympathize with her fretting that “one always has a better book in one’s mind than one can manage to get on paper.” And Richard’s imminent mortality is further darkened by the knowledge that there is no guarantee that his work will continue to be read as Woolf’s has: “There are so many books. Some of them, a handful are good, and of that handful only a few survive.”

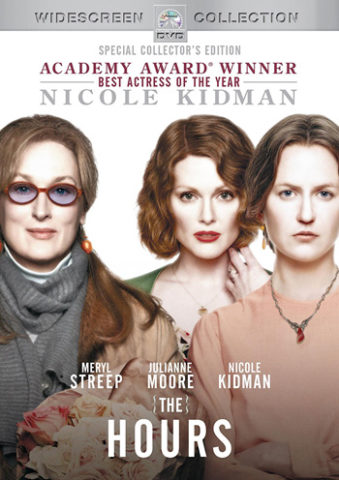

Beyond Mrs. Dalloway, The Hours (Woolf’s working title for what became Mrs. Dalloway) made me think of another gay writer’s relatively recent Pulitzer Prize-winning play, Three Tall Women, because there are three female protagonists. On the page more than on the stage, Cunningham had to make the three women credible from inside (internal monologs mostly, with some dialog). In the current “authenticity” worshipping zeitgeist, a man writing a woman (let alone three women) from the inside is suspect (though, fittingly, Richard wrote of Clarissa rather than Louis or himself).

As if there weren’t already a surfeit of intertextualities in The Hours, Vanessa Redgrave, who may be the celebrity Clarissa glimpses while out shopping and who has played “Mrs. Dalloway,” is going to appear in the film of The Hours. And, like Richard, Cunningham won a major prize for his novel about Richard’s reaction to a literary prize and the preparations for Clarissa’s party celebrating it. So it goes.

As I said, the denouement brings the three storylines together in surprising and fulfilling ways. Although reading The Hours will inspire most readers to read or reread Mrs. Dalloway, I don’t think that more than a vague sense of who Virginia Woolf or what happens in Mrs. Dalloway is necessary to enjoy and be moved by reading The Hours.

The Hours is a great, reflective book, though not of great length. Rarely there is a thought or feeling that seems underdeveloped. Cunningham creates rounded characters with an economy of words and has built a complex edifice in which the characters can breathe and move readers. It seems to me that what he wrote is as close to perfection as a novel—an irremediably messy form—can be.

published 12 May 2002 on CultureDose

©2002, 2016, Stephen O. Murray