The Homosexual Joke

The Homosexual Joke

by Joseph Hansen

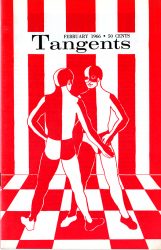

Tangents Vol. 1 No. 5

February 1966

Originally printed in the February 1966 issue of Tangents, pp. 26–30

An ability to laugh at himself may not characterize every homosexual, but the existence of camp alone suggests that witty self-awareness is an element of the group persona of the homosexual minority. Camp—extravagantly effeminate clowning—can of course, be the product of simple hysteria, a symptom of severe uneasiness in the individual, a mechanism of defense or rebellion. As a permanent behavior pattern it can be both futile for the actor and boring for his audience.

Camp, like much other humor, is funniest when unexpected. The more masculine the ordinary bearing of the man who uses it, the more successful it is. A brief unheralded flash of camp tends to provoke more genuine amusement than an all-night drag display with falsetto shrieks and feather boas. A single piece of camp furniture in an otherwise tastefully decorated room is funny. An entire apartment in Faggot Baroque is likely to evoke yawns.

“La Rencontre” by Brooke Whitney

In any case, whether as a cover for social insecurity, as a mating display, or merely as a laugh-provoker, camp is uniquely homosexual—a special brand of comedy belonging to an isolated group within the community. Recent attempts by outsiders to adopt the word and practice are testimony to its vitality. Perhaps they are more deeply significant and point in the direction of at least an amused acceptance of the way of life that produced camp.

But there is a wider and commoner range of humor devoted to homosexuality that the heterosexual world has long delighted in. Negro and Jewish stories told by whites and gentiles exist in plenty, and are often malicious. While there remain individuals whose sense of inadequacy makes them seek others on whom to heap derision, anti-Semitic, anti-Negro jokes will persist—and those directed against other easily identifiable and isolated minorities.

It is, then, paradoxical that there are few, if any, truly anti-homosexual jokes. There are certainly jokes that stereotype the homosexual. But the figures who participate in funny stories are rarely three dimensional. They are simply verbal puppets. Since quickness in the telling is vital to the humor of a joke, even a dirty joke, there is no time to characterize the participants. Here is a typical story involving a homosexual:

A big Texan in a crowded bar—handsome, broad-shouldered, something of a Clint Walker type—takes on a few too many drinks and begins to brag, in the immemorial manner of Davy Crockett and other frontiersmen:

I’m the roughest, toughest son-of-a-gun in this here country. I’m big and I’m bold and I’m bad. I’ve broke two hombres’ necks at the same minute in the same fight, one with each hand, like snappin’ matchsticks. I’ve picked up a four-room house and carried it on my back from one lot to the next. I’ve ripped up redwoods by the roots. Ain’t nobody stronger and harder than me. Look out! Lightnin’ flashes out of me when I get riled! Don’t nobody wave no red around here. Look out! I’m a wild Texas bull!

And down at the end of the bar, a small, timid type who has been listening and watching, wide-eyed with admiration, says: “Moo!”

Is this an anti-homosexual joke? It is hard to see it that way. But it is funny—if you haven’t heard it too often.

While we are in bar-rooms, perhaps we’d better attend to another classic.

A very effeminate young man is delighted to notice in his neighborhood a new bar that caters to the motorcycle crowd. One busy evening, passing it with a friend, he decides he simply must become a patron. Ignoring his friend’s predictions of trouble, he goes in, squeezes on to a stool between two hefty lads in black leather, and lisps to the bartender:

“Scotch and soda, please.”

The bartender squints ominously. “Look, get your ass out of here. We don’t want no faggots.” He nods to the two motorcyclists and they hustle our hero out the door.

His waiting friend says: “I told you.”

“That’s all right,” says our effeminate lad grimly. “I’ll find a way. I’ll show that nasty, hairy bartender.”

“How?”

“I’ll disguise myself, that’s how.”

“You mean in that old green taffeta?”

“Certainly not! You wait and see. You come into this bar tomorrow night at eight. You’ll see. I’ll be sitting right there drinking like all the other customers.”

“Okay,” says his friend, “but I’ll believe it when I see it.”

And the next evening, promptly at eight, he approaches the door. But just as he is about to open it, out comes flying his little friend, to land in a heap on the sidewalk. The door slams.

Slowly, painfully, our hero sits up, tears of disappointment in his eyes. “I just don’t understand it,” he says. “Look at me. I’ve got the crash helmet, I’ve got the leather jacket, I’ve got the Levis and the boots.” He holds out his hands. I’ve even got the gauntlets and—”

A look of realization dawns. “Oh, my God! My purse!”

Is any living homosexual hurt by such a joke? It is just sufficiently lifelike to pass muster as possible. But the teller—if he is heterosexual—has no real figure in mind. He has in mind a caricature the likes of which he can never have seen in real life. So who is hurt? There is even a kind of Chaplinesque pathos to such a story that belies maliciousness, a feeling of gentleness toward the little victim whose effeminacy is so ingrained he forgets to leave his handbag at home after all his efforts to get himself up in the most masculine costume he can imagine. This is generically a simpleton joke. We laugh out of sympathy for the little creature’s blunder because we too have blundered in life and it is comforting to know others have done so.

There is even some question, in a joke like the following, as to whether the heterosexual telling it is not ridiculing or at least calling into question his own set of sexual values, that of the society to which he conforms.

Two gay friends meet on the street, and one of them whispers excitedly to the other: “You’ll never guess what I did last night.”

“What? Who?”

“I slept with a woman.”

“Had sex, you mean?”

Vigorous nodding.

“Heavens!” Slight grimace. “What was it like?”

“Oh…” Small derogatory shrug. “It was all right. But nothing like the real thing.”

And in the following joke there is hint—again assuming the heterosexual orientation of the teller—of grudging wonder at the (supposed) sexual uninhibitedness of the homosexual, his almost magical prowess and imaginativeness in the sex act.

One is reminded of the wide-eyed folksay among ignorant whites to the effect that Negro males invariably have outsized penises.

An effeminate homosexual has picked up a truck-driver—muscular, hairy and gruff, the epitome of the masculine. We are among caricatures again—or still—comic-book types. We can rarely, in such a study like this, expect to get far from them. After much kissing and elaborate stimulation of his passive but willing guest, the homosexual wriggles close against him and whispers breathlessly in his ear:

“And now—I’m going to do something wonderful to you.”

“Yeah? Like what?”

“Something you’ve never had done to you before.”

“That I want to see.” The truck driver has been around. Even the heterosexual joke-teller knows this. In the simplified world of the dirty joke, truck-drivers are notorious gear shifters. “What are you gonna do?”

Answers the faggot: “I’m going to kiss your navel.”

“You’re kidding!” the truck-driver guffaws. “Hell, that’s been done to me a thousand times.

The faggot, with a wise little smile: “From the inside?”

A variant on this theme, this time with an ending that makes a victim of the homosexual, and attempts perhaps to join the genre of the malicious joke, but surely if not, at least defends the superiority of heterosexuality, goes this way:

The little homosexual, after methodically exciting his companion of the night, the same tough type as in the previous story—using all his erotic bag of tricks, feels he has aroused the man to the proper pitch of passion and whispers in his ear, “And now—what would you like?”

“I’d like,” says the truck-driver impassively, “a ham sandwich.”

The so-called dirty story has another type—the fantasy. In this, suspension of disbelief is required, or simple ignorance of the probabilities of life. In this genre we have two kinds. First is the fantasy of everyday life. For example:

A husband, worried by the sexual unresponsiveness of his wife, consults a doctor who gives him pills that he can administer to her without her knowledge.

“These will work?” be asks doubtfully.

“You bet they’ll work,” says the doctor. “She’ll be eager as a one day’s bride. You better be ready.”

That night, at dinner, the man drops a pill into his wife’s coffee when she isn’t looking. Then, fearful he may not be able to cope, he decides he’d better take one of the pills himself. He does so. And when she looks at him with a strange, passionate smile, and starts to rise from her chair, saying, “I need a man!” his answer comes in a high-pitched lisp, “You think you’ve got a problem!”

The fantasy involving disinterested wife, aphrodisiac pills and astonished husband repeats itself in endless variations. But the one cited here is an interesting reflection of the storyteller’s awareness of sexual ambiguity in the most commonplace settings.

This would seem to indicate a popular acknowledgement of sexual variation still lacking among psychiatrists and other “experts.”

The second type of fantastic joke escapes the boundaries of likelihood entirely. A perfect example of this bizarre genre begins with all the world’s radio and television broadcasts announcing:

“This is the Messenger of God. In exactly seven days I shall be coming to Earth.”

The message repeats itself. The world is in turmoil. The churches convene great conferences to discuss the matter. Governments consult. The F.B.I., British Intelligence, the French Sûreté, probe for evidence of hoax.

But the messages persist. The churches squabble over which shall have the honor of meeting The Messenger of God.

On the sixth day, their problem is solved.

“This is The Messenger of God. At exactly 11 o’clock tomorrow morning, I shall descend to Earth at the airport at Salt Lake City, Utah.”

Thousands rush by train, automobile, jet, toward the Mormon capitol. On the seventh day the crush of people is uncountable. From the airport a solid mass of humanity stretches in every direction as far as the the eye can see.

At last a murmur goes up from the hushed multitude. High in the cloudless sky a speck becomes discernible. The murmur rises to a roar as with great speed a round, blue, saucer-shaped object hurtles toward the earth, slows, and settles in the middle of a runway. Again an expectant silence falls. The Elder of the Church of the Latter Day Saints, who has been chosen by the churches to be their spokesman—since Salt Lake City is the landing place the Messenger has chosen—nervously wipes his forehead and clears his throat. All eyes are on the strange, glowing aircraft.

Then a little door in the side slides open. Down shoots a tiny gangway. And down the gangway comes a little green man, The Messenger of God.

The crowd stands breathless. The Elder’s prepared speech of welcome drops from his fingers. In awe he kneels. And in the enormous silence all the gathered thousands likewise kneel. Finally, the Elder manages to stammer out a childlike question:

“Tell us about God.”

“Well …” says the little green man, mincing and flitting, hand on hip, “in the first place, She’s colored.”

The joke shocks with its irreverence and unpredictability. Beyond these obvious qualities lie deeper implications, and sober ones. For, given a moment to reflect on the story’s whole meaning, we are left with, of all things, a moral in the good old Aesopian sense. The story that seemed so fresh, with its science-fiction trappings, is in fact merely the old cautionary tale about “entertaining angels unaware.” Look out, says the moral, when you mock Negroes and homosexuals—you may be mocking God.

To the making and telling of jokes there is no end. To this sketch for a survey of homosexual humor there must be. But it too has a moral.

To the argument that the public finds the subject of homosexuality too distasteful even to think about, let alone talk about, the growing number and sophistication of jokes involving the subject gives the lie. And this is good.

If homosexuals are being laughed at and stereotyped, they are as often being laughed with and understood. A side of our national life too long dark and unmapped is being lighted and charted—fitfully and clumsily perhaps, but from the best of motives, not with the desire to “cure,” “reform,” “stamp out,” but the simple desire to laugh. In the area of comedic folksay, where most minorities fare badly indeed, the homosexual appears to have it made.

If homosexuals are being laughed at and stereotyped, they are as often being laughed with and understood. A side of our national life too long dark and unmapped is being lighted and charted—fitfully and clumsily perhaps, but from the best of motives, not with the desire to “cure,” “reform,” “stamp out,” but the simple desire to laugh. In the area of comedic folksay, where most minorities fare badly indeed, the homosexual appears to have it made.

©1966, 2016 by The Tangent Group. All rights reserved.