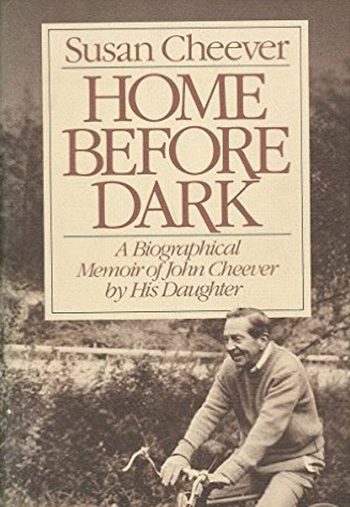

Home Before Dark

Home Before Dark

by Susan Cheever

Published by Houghton Mifflin

Published November, 1984

History (biography)

243 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

January, 1985.

While in high school in a small Minnesota town during the late 1960s, I spent most of my weekly violin lessons discussing literature with my teacher. I must have done most of the talking, because I was shocked to read an interview with her in the school paper in which she said her favorite writers were Dostoevsky and Updike. Being Russian I considered an excuse for her choosing Dostoevsky, but Updike? I was certain that John Cheever did better what Updike tried to do. I recognized that both wrote many splendid sentences, but Cheever’s seemed to me to add up and Updike’s didn’t. The suburban society and behavior each wrote about was almost as remote from my experience (which was pure Sinclair Lewis) as those Margaret Mead wrote about, so my feeling that Cheever wrote about life and Updike didn’t can’t have resulted from the suburban New York setting or the behavior (mostly adultery) both Updike and Cheever detailed.

Since my last violin lesson, I have lost some of my adolescent certainty, and Updike has written some books I care about. . . And reading Cheever’s daughter Susan’s [born in 1943] memoir, Home Before Dark, I came to realize that part of how Cheever spoke to me was by ringing a responsive chord of unacknowledged homoeroticism. I didn’t know love, still less sex, was possible between men and didn’t at all recognize I longed for love. Although I was seething with inchoate longings, I was perceived to be “The Brain” of my class, and therefore necessarily devoid of any feelings (“A rock feels no pain, and a micro-chip never cries”). Unlike Cheever, I was never called “sissy.” In my school that role had already been cast, and I was as contemptuous as anyone else. Therefore, I didn’t have a specific fear of being “queer,” and didn’t invest any time in trying to figure out what a “queer” was or how someone who was one might feel. Cheever, propelled by his parents’ expressed fears that he was unmanly, chose not to be a queer and repressed his longings, though they appear masked in many of his stories and more and more overtly in his novels.

Part of my early veneration for his work must have stemmed from the subliminal reassurances they provided that I was not the only man who was attracted by men. The characters in his stories don’t know what to do with these feelings, even when they recognize them. Cheever himself fled them—into marriage and alcoholism. In his daughter’s judgment, “It was partly his fear of his own desires that kept my father drinking, and I think his anxiety over his sexual ambivalence also kept him married.” An army officer he (unsuccessfully) attempted to steer into a sexual relationship reported, “I knew it was love for him. He said he knew nothing about technique.” Thus, it’s not surprising I didn’t receive the instructions I needed about what to do with either my body or my feelings from his writing. I learned elsewhere as the 1970s began. By the end of them, Cheever, too, had learned, established a durable relationship with a married (hence not “queer”) man, achieved a measure of serenity, and written his masterpiece, Falconer, a novel in which a wreck of a henceforth heterosexual man not unlike John Cheever in the late 1960s is redeemed by the love of a young man, not unlike Rip.

Susan Cheever recognizes that as obvious was the evidence, the family did not want to know about her father’s homosexual relations. Similarly, there were readers of Cheever’s great novel Falconer who denied that the central relationship was homosexual, because the older man helped the younger to escape from prison instead of keeping him with him. (As criminologist Laud Humphreys pointed out, aiding his young lover to escape the hellhole of prison was the ultimate, selfless expression of love. The homosexuality was not “situational” but was the basis for the rebirth of the one who remained in prison but had transcended the prison of his self-hating, alcoholic self.)

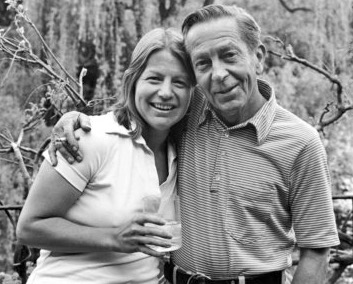

In real life no such noble sacrifice was necessary (or possible). John Cheever would have been irritated that an admirer of his work would look for clues to his work in his life, just as he would be appalled by my youthful attempt to establish his superiority to Updike (“Literature is not a competitive sport” was a refrain), but as surely as the life was deeply flawed, the art is not. I believe the life illuminates rather than discredits the work. Indeed, Susan Cheever’s luminous memoir (which is indubitably about life as well as being fine writing) is itself art. I’d say it is more art than edification, for although we learn from reading it, the life described is not one many would envy or seek to emulate!

Like Mary Catherine Bateson (who first revealed the bisexuality of her mother, Margaret Mead, in With a Daughter’s Eyes), Susan Cheever followed her famous parent into the same fields and had to emerge from the long shadows of her father’s fame—and to overcome parents’ discouragement of following (competing with?) them. Both are respectful of the Yankee traditions of John Cheever and Margaret Mead, though not so obsessively as their parents were .

One of the striking facts of both memoirs is that the spouses did not feel threatened by or jealous of the lovers. Mary Cheever had many grievances to list against John, but his male lovers don’t seem to have been items on the list. (Similarly, Gregory Bateson resented much of how Margaret Mead lived, but not her attachment to Ruth Benedict.) John Cheever wanted people, his children included, not to know about his homosexual relations. Although they were also not eager to know, they unquestioningly accepted his primary partner, Rip, into the family.

These two books reveal something of the enormous complexity of relationships mixing marriage, family, and homosexual liaisons: John Cheever simultaneously played the roles of father, husband. and homosexual lover; Mead those of wife, mother, homosexual lover. Well-balanced, creative children somehow emerged from these stormy and unconventional households. That children stem at all from the homosexually-inclined will be a revelation only the Christian Right. What might reassure lesbian and gay parents is the love and understanding exhibited by the authors of these memoirs. Both daughters are pained more that their parents did not share more of their lives, loves, and fears with them than they are upset by any “scandal” of having homosexual parents.

Earlier versions of this review appeared in a dual review (also discussing Mary Catherine Bateson’s With a Daughter’s Eyes in the Anthropologists’ Research Group on Homosexuality Newsletter in January, 1985, and on epinions in 2007.

Also see my review of John Cheever’s final novel, Oh What a Paradise It Seemed, here.

©1985, 2016, Stephen O. Murray