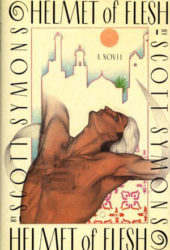

Helmet of Flesh

Helmet of Flesh

by Scott Symons

Published by Dutton Adult

Published August 22, 1988

Fiction

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

July 6. 2009

Toronto-native Scott Symons (1933–2009) was said by Sandra Martin to have a “thick helmet of black hair, a chunky wrestler’s body and a magnetic personality.” Hair was not what Symons had in mind in titling his 1986 novel based on experiences in Morocco in 1971 Helmet of Flesh. Rather, that was his metaphor for an uncircumcised (and in the novel invariably large and black) penis.

There are a number of male-male sex scenes in the novel, though so filtered through metaphors like “hemet of flesh” that I could not call them “graphic.” Ejaculations are invariably floral (bouquets of them). The novelist’s alter ego, the befuddled protagonist of the book, York Mackenzie, has sex with dark-skinned Moroccans (originally from the Atlas Mountains just above the northern edge of the Sahara Desert) who though young seem to be of legal age.

In an auto trip with more than passing resemblances to that in Paul Bowles’ The Sheltering Sky, except all male and with a young “native”[1]Politically incorrect, “native” very well captures how the Anglos in Helmet of Flesh saw the Moroccans. There are recurrent references to Kipling though the phrase “white man’s burden” does … Continue reading man, Kebir, to attempt to protect the two Englishman and one Canadian man. One of the Brits (James) flirts (and more) with native males ranging widely in age while the other (“The Colonel”) diddles youngsters and has to be classified as a pedophile. As in The Sheltering Sky, one of the norteños goes off with the Tuareg.

Kebir on one trip into the mountains and Juba in another are idealized as the naturally poised, infinitely polite, and quite resourceful archetypes of sexual freedom beckoning emotionally constipated Canadians and Brits. What I call “neocolonial desire” is a peccadillo in the Colonel, a nihilistic temptation for James, and spiritual enlightenment for York, whose appreciation for young native males is in his and the author’s view different and superior to the compulsive pursuits of young native males by James, the Colonel, and expats back in Marrakech (where York meets Kebir and from which his two trips into the mountains are launched). I can’t imagine a plausible challenge to the charge of “racial fetishizing.”

Those who are alright with the discreet pedophilia, more blatant pederasty, and the still-colonial adoration of the noble Kebir still have other obstacles: the very rambling narrative with jump cuts skipping over both return (to Marrakech) trips, jottings from York’s journal that deride Canadian identity and culture, tourists (especially German and American ones), and range from unkind to vicious about the fellow non-Moroccans who feed and shelter York, transport him, and keep him alive.

York strikes me as an irascible freeloader. I do not understand why anyone would take an interest in him, let alone underwrite his adventures. I gather that Symons was also an irascible freeloader, who found support from some gay admirers.

Which reminds me that York, who, like the 34-year-old Symons, had left his wife and young son and run off to Mexico with a 17-year-old son of a prominent Toronto family (called James in Helmet of Flesh, John McConnell in real life), had sexual relations with many young male Moroccans while living in Essaouira, and still made much of not being “homosexual,” not being “gay” (and also maintained that Kebir, who had had an earlier European male patron, also should not be stigmatized as “gay”). The kind of homosexual homophobia of York reminds me of that evidenced in James Baldwin’s Giovanni’s Room (by the narrator/character David, who also yearns for amorous isolation à deux and bemoans the corrosiveness of any homosexual sociation).

There does seem something to offend most everyone in the book, including gay ones. Perhaps not French people, though they might look askance at York’s ostentatious claims to fluency in French.

Still, there are some powerful scenes of derangement and sort of ecstatic paranoia (similar to but more coherent than Alfred Chester’s writings about his Moroccan same-sex (but not in his view gay) amours. And some acid-tinged bon mots. Also, I bogged down during the recovery from York’s first trip, back in Marrakech, as York hallucinated about Canada (a ramshackle coastal paradise of sorts across Canada from Malcolm Lowry’s; York is not a drunkard but has much of the grandiosity of the Consul imperiled in Under the Volcano).

In addition to being the final (third) novel of a writer who was born and who died in Toronto, there is “Canadian content” in Helmet of Flesh. York has a collection of essays about Canadian identity and culture that he is supposed to be working on in Marrakech. Also there are extended flashbacks to the Newfoundland west-coast fishing village where York parked John/James: Osprey Cove in the book, Trout River in real life. Also, “he dreamed of writing the great Canadian novel—a visually creative and sexually revolutionary work that would liberate readers and empower them to embrace hedonistic experience and shrug off the complacent shackles of postwar Canadian society” (Martin).

That Symons was even more unbearable than York is a conclusion I drew from Sandra Martin’s obituary of Symons.

First published in Elvisdo’s Canadian writeoff on epinions, 6 July 2009

©2009, 2016, Stephen O. Murray