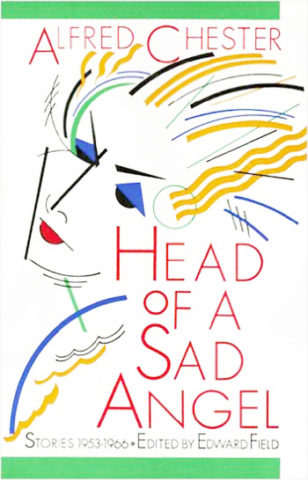

Head of a Sad Angel:

Head of a Sad Angel:

Stories 1953–1966

by Alfred Chester

Published by Black Sparrow Press

Published August 1990

Fiction (historic/memoir)

375 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

February 27, 2003

Until I read Greg Mullins Colonial Affairs,[1]which I reviewed in the Journal of Homosexuality 47 (2004):170–178. in which Alfred Chester (1928–71) is discussed as an equal of—or at least at roughly equivalent length to—Paul Bowles and William S. Burroughs as writers about Americans renting young Arab studs in Tangier, the only writing by Chester I’d read was a vicious review from the first year of The New York Review of Books of John Rechy’s City of Night. [2]The review is reprinted in a collection of works from the first year of NYRB and in a collection of Chester essays, Looking for Genet.

First reading about Chester and then reading the 1990 collection of Chester’s short fiction, Head of a Sad Angel, it became obvious that if Chester had encountered John Rechy’s autobiographical narrator (or Rechy himself) on a cruising ground, he would have gladly dropped to his knees or bent over to be topped by him. Chester’s “type” was brown-skinned, masculine, and disdainful of queens like Chester—queens like Chester who avenge the abjectness of their desire for their social and intellectual inferiors (those they suppose to be inferiors because it is unbearable to think someone could be desirable and an intellectual equal) with cutting remarks on the page or in the company of other connoisseurs of hard brown bodies and of one particular body part (not the small “Kikuyu” ears that are not what one sees on the photo of Dris, Chester’s Moroccan love object and fantasy fulfillment that is included in Colonial Affairs…)

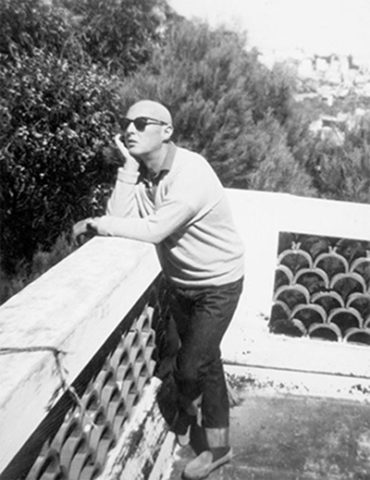

Chester’s writings exhibit plenty of ambivalence for those he worshipped, though he did not always despise himself for the deficiencies of his love objects. Being physically grotesque (having no hair anywhere including on his eyebrows as a result of childhood illness and its treatment), a flabby, wig-wearing, middle-aged man already at age seven, Chester was also extremely prickly. Starved for love, certainly, but a monster, Chester alienated all his friends and seemingly abandoned Dris, the Moroccan he mythologized as the love of his life, in Europe without any money or papers—or explanation.

Chester also exclaimed about being heartbroken that he had been expelled from the semi-paradise of Morocco and barred from return. He gave the impression that it was some too-public homosexual excess that led to his expulsion, but one of the memoirs about Chester (which are mostly more interesting than what Chester himself wrote) reports:

It was not, as one might think, because of sexual indiscretions, but because of his quarrelsome behavior, which sometime bordered on madness. He had been living… in a little fishing village…[w]here he was given to warring constantly with his neighbors. Intolerant of any sort of noise on the part of playing children, he would storm forth from his house to beat them. His neighbors would not stand for this, and battles involving sticks and stones would ensue. The police would often appear on the scene, and appeared once again when his landlord would not tolerate Alfred’s damages to the house he had rented him. It was not only that Alfred had piled one of the rooms to the ceiling with rotten oranges, but he had broken through the wall of one of his rooms to save time getting out of the house.

Fittingly, Chester’s greatest commercial success (seven years earlier) was a story for which New Yorker paid him $3,000 (enough to support him for two years in Morocco or to pay his Manhattan rent for more than four years) titled “A War on Salamis” (included in this collection) in which an American rents a house on the Greek island of Salamis and soon is at war with his landlady and eventually forced off the island. The protagonist presents himself as the protector of an inhumanely treated dog, but he also displays considerable animosity to children making any noise.

“A War on Salamis” is the only one of the early stories (written in Paris, 1953–59) in this collection that I find very interesting. It has some structure (even a plot of sorts) and plays in the key or irony more than that of self-pity. (The Parisian stories are more surrealist than the Moroccan stories that Mullins labels “surrealistic.”)

The four New York stories (1959–63) sometimes arch but have some shape. One, “Beds and boards,” is about the final night of a heterosexual couple before the wife leaves with the children. The other three are about failed same-sex love. Well, another one,”From the phoenix…,” is set on a night in which another wife (I think they are married) leaves the man who had earlier been the narrator’s boyfriend.

Two of the three Moroccan pieces (1963–66) are sets of jottings in which sex-for-payment between Arabs and “Nazarenes” (the Moroccan Arab term for Europeans and Americans, including non-Israeli Jews) is discussed more than shown. Between them is a fairly straightforward narrative, though it is a narrative about a fairly absurd endeavor: scorpion hunting out in the desert.

The longest piece (53 pages), labeled a “novella,” “The Foot,” is in the form of a journal, presumably from 1966. It includes recollections of the youthful trauma of hair loss and the subject of wigs, which Chester never permitted discussion of in his presence; bile about New York(ers); and lyrical outbursts about love for a Moroccan called Larbi. Although the journal writer at one point kisses Larbi’s ankle, it does not convince me (as it does Mullins) of foot fetishism. In what seems a Burroughs-like denouement, the kissed spot festers. Instead of transforming frogs into princes, Chester’s kisses turn princes into frogs—though the croaking is Chester’s bemoaning his passions not being reciprocated:

I would do anything to please any of my lovers. I can almost vomit at the thought of it, but only because they haven’t done anything to please me back.

Chester’s style is savage and incantatory, as Gore Vidal remarks in a foreword to the volume. Chester does not often give way to self-pity, but he recurrently does. His writings display little compassion for other human beings, though a bit for stray dogs on an Aegean island, and mythologization of one fellow seeker/martyr of a priapic cult (“In praise of Vespasian,” the story which Vidal says showed that Chester was a master, “but a master of what was not quite clear”).

Including some letters about finding the MacDowell writers’ colony unbearable and being expelled from it, a 74-page “appendix” includes biographical sketches and memoirs of Chester by Edward Field (editor of the volume), Cynthia Oznick, Jean-Claude Van Itallie, Dennis Selby, Norman Glass, Ira Cohen, and Robert Friend.

Perhaps the final irony is that a Jewish Jew-hater died in Jerusalem (in 1971 at the age of 40, already forgotten).

first published by epinions, 27 February 2003

©2003, 2017, Stephen O. Murray