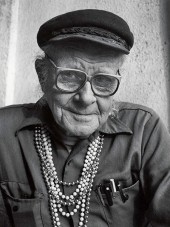

Harry Hay

Interview by Mark Thompson

as published in Gay Spirit: Myth and Meaning

The HIC is grateful to Mark Thompson and White Crane Books for permission to publish this historic interview. This material is copyright protected and may not be reproduced without permission from the author and publisher. Image by Robert Giard.

See also: Mark Thompson’s biographic essay, “Harry Hay: a voice from the past, a vision for the future”

THOMPSON: What were the early days of organizing like?

HAY: When we first started the society, we were aware of the fact that we had no literature, nothing to go on. As we would learn several years later through chance visitors to one of our discussion groups, there were social groups in several countries in Europe who occasionally put out small magazines. But—until the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision for ONE, Inc. in 1957, the U.S. post office refused to allow such materials to be mailed in this country. Such magazines as there were in the United States in 1950–52 would have been brought back by travelers. The original Mattachine founders and early society members were mainly left-wing political activists who didn’t then number European vacationists among their acquaintances.

So, as I said, when the first five of us started to meet, we met five to six days a week after work, often until one o’clock in the morning. As far as we knew, we were the only people who had ever tried this. And because we didn’t know any other group that had tried it before, there were no guideposts to go by. We felt we couldn’t (afford to) make a mistake, because if we did, we might possible deter the movement from developing for years to come. After all, we were facing McCarthyism and the Hollywood Ten[1]The Hollywood Ten was a group of writers and directors blacklisted within the motion-picture industry for their refusal to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee.—all this was happening in 1950–51. So we operated by unanimity, which meant, among other things, the meeting over weekends would often last sixteen to eighteen hours.

We set up the group on a cell basis because there were quite a lot of people who started coming to us who were security cases—working for the aircraft factories and all of that. We felt that the best way to protect everybody was to say that the people involved with one group would know only a single person from the other.

Then there was no way of passing on common experience?

That we had had experiences in common that were shareable—even when we were under the illusion that we were the only one of our kind in the world—that all our lives we had been accumulating experiences to be shared, were the wonderful discussion group revelations we had not yet discovered.

At this moment in 1979, it is difficult to project what our position in 1950 was like. Homosexuality was not only immoral but illegal—and therefore criminal doings of degenerate heterosexual perverts … we didn’t have a protection to our name!

So I had conceived our public face as being that of a philanthropic group that would be a nonprofit foundation fostering and hosting semi public discussion groups based on The Kinsey Report, which had been published two years before.[2]The Kinsey Report was a groundbreaking, in-depth study of sexual behavior among many thousands of American men and women which revealed a much higher percentage of homosexual behavior in the … Continue reading This was the Mattachine Foundation, composed of women of some standing in the community—business women, club women—and three men: a well-known labor lawyer, a practicing clinical psychologist, and a Unitarian-Universalist minister.

But the real prime movers of the foundation’s discussion groups were gay brothers in groups of ten in a closed society hidden behind the facade of the foundation. This group, consisting of what in the gay liberationist 1970s would be called a “consciousness-raising” collective, consisted of nine brother-sister members and a guide or counselor who would be their one contact and connection to the larger society.

If you came, for instance, to one of the foundation’s discussion groups and showed interest by participating, we’d make a point of engaging you in conversation afterward. If we sensed you as a brother, we’d invite you a second time. If you warmed up and began to express feeling the second time, one of us would make a date and take you to dinner and, in the course of the evening, share our “call” with you. If you responded favorable, you were invited to our next consciousness-raising meeting in the curse of which our collective family circle suddenly opened to enfold you and welcome you home.

We were speaking of the dream of the marvelous brotherhood that gay people can be. I spoke of the feeling of love for one’s own kind that is born in the hearts of each one of us—which we know is a beautiful thing, but everyone else thought bad. We were still being rather amorphous and indefinite because we didn’t have a way to express it yet. We hoped that by being together, we would find a way. In the discussion groups, we faced the fact of what the gay lifestyle was like and what it could be.

What were the alternatives then? What were the bars like, for instance?

We didn’t have many, and such bars as we had were generally miserable places—a dirty light bulb in the ceiling and sawdust on the floor. And always, total fear of being turned over anytime to the police. You couldn’t show any sort of intimacy, like holding hands—and you’d never kiss or you’d get knocked over by plain-clothes men who were there all the time. So you lived in terror most of the time.

The first time we gave a dance, which I think must have been in 1951, we invited people openly and sent out a call in a great many places. It was a summer night, the doors were open, and people were coming in off the street. We had maybe fifty or sixty people in this house. I remember one young typist from my office who brought three or four rough street people who were used to picking up sailors—that was their life. They were standing in the doorway weeping and saying they’d never seen sixty men dancing together before in their lives…but thirty gay male couples dancing together and being openly and joyously themselves was more than they were prepared for. We still danced in ballroom couples in those days…I think that Rudi and I were doing a Viennese “showcase-type” waltz when Phil and his friends came in.

Did many gay people regard themselves as second-class citizens?

I don’t think they even thought in those terms. We thought of ourselves as being illegal. The idea of self respect didn’t exist. We were talking about this for the first time. We were talking about the right of self respect and to appreciate that we are strong, not weak people—that “sissy” means a stubborn person who’s put up with an awful lot of stuff and comes through being exactly what he is. A lot of people were saying, “My God, I never thought of that.”

Were role stereotypes very extreme?

We had our problem with this. I raised the question, “Am I my brother’s keeper?” I spoke of this to the street queens as well as butches. An awful lot of people weren’t ready for this. Maybe one of the reasons I got thrown out in 1953, in addition to being a “radical red” and giving us all a “bad name,” was that I kept saying, “Let’s hold out hands and work to hear and see each other.”

The conservative elements didn’t like this at all.

The other thing they didn’t like was my insisting that gay people were a social minority. I didn’t even call it a subculture. I said, “We have our own culture, and we have to explore and find out about it. We’ve had a culture for hundreds of years, and it’s high time we recognize our significant contributions.” They fought the idea like cats and dogs.

So the concept that we are just like everybody else, except what we do in bed, was very strong?

Very strong, yes.

The founders of the group were saying, among other things, that this was not true—that we are different in a variety of ways. The questions “Who are we?” “Where have we come from?” and “What are we here for?” were questions we began to ask ourselves in the discussion groups very, very early.

A lot of people didn’t want to look at that because it meant that they were going to have to do a lot of thinking, a lot of reading. To do research at this time was almost impossible. We didn’t yet know what to look for.

I had been given a book by a lover, back in 1937 by the great Charlottenburg Institute authority Dr. Iwan Block, privately published by the Falstaff Press of New York.[3]Dr. Iwan Bloch was a turn-of-the-century sexologist whose works include The Sexual Extremities of the World and The Sexual Life of Our Times in Its Relations to Modern Civilization. His … Continue reading I also had copies of studies by Westermarck and Carpenter, and Rudi gave me a copy of Andre Gide’s Corydon. But none of these texts talked about contemporary social or political gay societies, or even study groups. They were concerned only to justify homosexual practice through detailed discussions of historical incidences or medical and missionary journals reporting anthropological observations around the globe. Pretty much “apple and fish” (non-related) material, to be sure—but we would have little else until Ford and Beach’s Patterns of Sexual Behavior, whose appearance was still some years in the future.

We realized that we were going to have to go back to all the books on history ever written and read between the lines. We had to go back into mythology and suppose, interject, wonder, ask questions about—to get the sense that we were going to be finding ourselves between the lines. Certainly not in the front pages anywhere.

Earlier I had been part of a group called People’s Songs—Pete Seeger, Lee Hays, Jenny Wells and Woody Guthrie on the East Coast, Earl Robinson, Billy Wolfe and me on the West coast.

We had collected a lot of books from various places, as well as songs and words. We were beginning to put them down in collections; but, more important, just after the war in 1945, 1946, 1947, there were a lot of problems that had to be worked out. Labor was just beginning to become strong, and there were struggles against rent raisers and gougers everywhere. There were strikes and picket lines and evictions all over the place.

So we said, “Here are all these wonderful tunes, and a far as we can see, folk tunes play their part.” The words come in and the words come out as they are needed in political and social situations.

Well, then a group called the People’s Education Center in Hollywood began a number of courses in political science, economy and history. They asked if we’d like to teach a course in the history of people’s music.

So these were the classes that were later used to describe you as a Marxist?

Yes, which is true, because I was teaching them on a Marxist basis.

In the course of doing that, however, I came across a very interesting group in twelfth- and thirteenth-century music. They are a group in France known as Les Societes Mattachines and were men who dressed as women. Their leader was always known as Mother Pig. They were found in many places in France and Spain, and a particularly interesting thing is they were usually clerks and whenever they appeared in public they were masked. They were educated people in the cities who could read and write, yet who went out to the countryside dressed in costumes while performing songs and rituals for the peasantry. These were rituals that the peasants themselves were either too afraid to enact or forbidden to do so by the lords.

These people were lifelong celibates within the societies; they did not marry. They were former clerics now living and working as a secular group but also “religious” in that they took old magic rites from the Great Mother religions of the peasants to perform. I have always assumed they were gay people. You don’t dress as a woman or take on the job of shaman lightly. Often they were wiped out by the lords of the manor, who felt their rituals were similar to a peasant uprising.

What I’m getting at is that members three, four and five came out of one of my classes. And when we were trying to figure out a name, they finally suggested that we take “mattachine” and make it into English. We liked the name because when we told gay people about its history, they would recognized themselves and each other in it. It’s part of our history, but people would have to ask about its meaning. We thought this useful.

What happened to the original organizers when the group split in 1953?

A couple of us went through a couple of years of total trauma: A couple of us never related to the gay movement again in any way … Rudi Gernreich, for one—We’d been lovers during Mattachine’s first years—who dropped away to begin his career as a world-famous designer. And the wonderful lesbian who had brought us all such loving and at the same time, such critical support also dropped away from both Mattachine and the gay movement. She has gone on to become on of the great women photographers of the twentieth century, but she also never lent her name to the movement again.

The real heartbreak for the original organizers was not so much that the movement split but that our beloved Unanimity had failed. We had never in a million years conceived that such a thing would happen … the Magic carpet had fallen to earth. The middle-class faction was at the point where they believed they were not only exactly the same as everybody else except in bed but that gay people actually had nothing in common except their sexual inclinations—a position many of them continue to maintain to this very day.

Well, the golden Mattachine dream was gone—vanished—and our sphere of influence of about five thousand people in California alone soon dropped to about five hundred. There wasn’t any call anymore. There was nothing … The loving cement that had held us all together had relapsed into mud.

One of the things we had done a year earlier was to bring back the Feast of Fools. We were trying to bring back rituals in one form or another. The Feast of Fools featured the Lord of Misrule. He who is not what he appears to be turns over in this period. The high-born and lowly traded places with one another—the bishop became the acolyte, and the acolyte the bishop, and all other classifications were equally turned inside out in this fortnight that immediately preceded the Feast of the Great Earth Mother Oestara, or the vernal equinox. We had wanted this ritual to help us all “turn ourselves inside out”—to, in effect, tear off our workaday masks. We had hoped this could have been the beginning of a cementing of what we dreamed to call the Guild-Circle Family.

But when the split occurred, the feeling of brotherhood totally disappeared and the so-called democratic movement—the old hetero-imitating tyranny of the majority—reappeared: Once again they were electing presidents and first and second vice-presidents and all that jazz.

But I myself was no longer willing to retrogress back to that hetero-imitating, subject-object, white-man, middle-class obsolescence. I never joined any of the conventional Hetero-imitating type of gay organizations again: I vowed that I would never have to submit the golden treasure of my heart, my vision of gay consciousness, to the ugly and distorting vicissitudes of Robert Rules of Order … ever again!

It wasn’t until 1964, a year after I had met John, that we revived the name Circle of Loving Companions, and made it ever a channel through which those who wished to dissent could be heard in the years between 1965 and 1969. The Circle of Loving Companions was very active and quite vociferous in those years. But we made it quite clear that we would walk with those with whom we acquiesced, so long as we were both going in the same direction—but only then! In keeping with some of these concerted actions, John and I were not only on national radio but also on national TV—as an openly gay couple expounding positive values to our gay lifestyle.

When Stonewall broke in 1969, what effect did it have on you? All of a sudden everyone was talking “gay lib.”

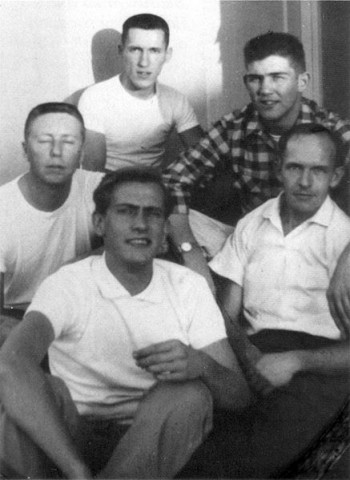

Image by Diana Davies, © New York Public Library

The idea of people coming together in a loving consensus—these words, “loving, sharing consensus,” suggest we had much in common—was exactly the opposite of the old middle-class groups who would always assume we had nothing in common but our sexual inclinations. It was a whole other ball game. Over and over again, we called for gay people who would stand together hand-in-hand. It was a family get-together.

Somewhere along in here, the word “gay” began to be used to describe us. Prior to that time we were homosexuals. Reporters began to feel pressure to deal with gay people, and the word homosexual was a headliner’s nightmare. “Gay” gave us a name for ourselves around which we could put a sense of common nature and heritage.

I first used the term “gay window” in an address, subsequently published by The Ladder, to the Western Homophile Conference in February 1970. I had come across this concept the summer before and worked it out as a logical process.

For instance, every woman knows that there is not a man living who understands what it means to be a self-loving, self-respecting woman. Every black know the same about a white person. Every gay know that no heterosexual man or woman knows what it means to be a self-loving, self-respecting gay brother or lesbian sister.

Gays have a special window, our own way of seeing, our own vision.

We know how heterosexual men and women operate because we had to learn in order to survive, to get through school. But we also know that what they do to each other is very different from what we feel about ourselves.

Now remember, this was 1970. What was wonderful was just in saying that. All those faces in front of me began to glow—particularly, the young people’s. After I got through speaking, they all came over to tell that they had been seeing through that gay window all their lives. All I did was help them see what they already knew, but now they could talk about it because they had a word for it. It worked as a trigger. I tried it again and again, and it always worked.

So you feel that gay people carry an innate, collective body of information about themselves?

I think we’ve carried it in our genes for a long time. We need these triggering mechanisms to awaken them. In a way, this is what happens to scientists when all of a sudden a new vision, a new idea comes. They have to invent new models, new words to describe what they’ve seen—a poetry or a mathematics. We have to find models to explain that body of information and knowledge we’ve been carrying for a long time, but which has no way to get out. We must be able to communicate this vision with each other and then to the world at large.

What is this vision? What are the characteristics of it?

All of us grew up knowing that we had a secret in ourselves that was different from other people. And regardless of what we heard—that it was dirty, it was bad, it was against God—we somehow knew that it was beautiful and good. We didn’t know how to express it, but we had faith that someday we would.

Then that wonderful day comes when you find that you’re not alone, that there are others like you. You begin to fantasize that there is going to be that one who understands you and has gone through the same things. And the day will come when you’ll take his or her hand and understand and share everything perfectly.

The thing was that, all the time, you were thinking about yourself, the subject. And when you start to think about that other, you’re still thinking the same way as about yourself … you’re thinking of him, of her, also as subject.

Humanity must expand its experience from people thinking objectively—thinking subject-to-object: that is, opportunistically, competitively and nearly always in terms of self-advantage—to thinking subject-to-subject, equal-to-equal, sharer-to-sharer, thinking in terms of loving-healing.

I say at this point now that we are the people with subject-subject vision. This is what we have to contribute. We must call to people to exercise the subject-subject relationship.

And unless gay people begin to think this way and become conscious of it, we’re not going to be able to apply it. We’re going to have to reexamine all heterosexual-male thinking systems. We must recognize that there is a qualitative difference between heterosexual social consciousness and gay social consciousness. And our first responsibility must be to develop this gay consciousness to its deepest most compassionately encompassing levels.

We are at a point now where we have to reinvent our movement in ways we never thought of before. In a sense, the earlier homophile movement and gay liberation movement were movements reactive to heterosexuals. For the first time, we have to create a movement that doesn’t start with them, but within us. We can’t keep going the way we are now. There has to be a breakthrough in consciousness. Gay people have a tremendous role to play there as healers, as teachers—things we already are.

Are we in danger of losing touch with this insight, especially as we become more accepted by society?

As I said, we pulled the ugly green frog skin of heterosexual conformity over us, and that’s how we got through high school with a full set of teeth. We know how to live through their eyes. We can always play their games, but are we denying ourselves by doing this?

If you’re going to carry the skin of conformity over you, you are going to suppress the beautiful prince or princess within you.

The actual good of the marketplace—the ghetto in San Francisco, as an example—isn’t worth it. I think that capitalism is a little bit closer to the end of the road than it used to be. And when a new way of living comes about, and if you’ve thrown off the frog skin and found out who you are as a gay person, you will be able to adapt to this new circumstance.

We’re saying that this whole marvelous thing of being gay, of being a fairy, is much more than just the beautiful part of our sexuality. There is more to be explored and discovered. We’re calling on gay people to come out and fly. This is what we think the movement of the age is.

I think part of the confusion of running here and there and wanting one high after another is a lack of groundedness, a lack of knowing who we are. I hope in the 1980s we’ll be coming together in different ways. This is one of the things we’re trying to do over the weekend. It’s the first time, to my knowledge, that a call has gone out like this on a national basis. It’ll be a place to share, to see what’s going on. And while we’re doing that, we will also be touching and holding each other. We will be dancing together, and with luck we’ll learn to levitate—as fairies should.

So when you ask what we have to contribute, we have nothing less than a whole new way of relating—which is the most ancient way of relating—subject-to-subject. We must rediscover and celebrate.

See also: Mark Thompson’s biographic essay, “Harry Hay: a voice from the past, a vision for the future”