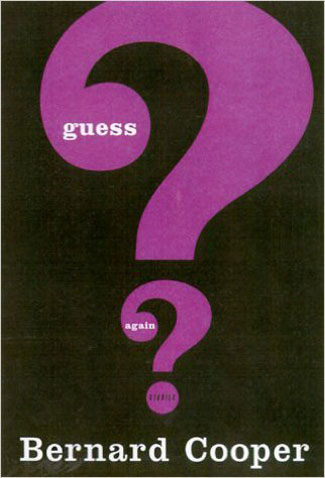

Guess Again

Guess Again

by Bernard Cooper

Published by Simon & Schuster

Published November 9, 2000

Fiction (anthology)

208 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

June 19, 2001

Although melancholy and regret hang heavily on some of Bernard Cooper’s memoirs and fiction about his childhood broken home, what he writes about gay life—his own and that of others—is often wildly funny (“funny but not jokey, moral but not preachy,” as David Sedaris’s book-jacket blurb for his short story collection Guess Again aptly puts it).

It seems to me that Cooper is better at setting up stories and sketching quirky characters than he is at devising satisfying endings. Even the best stories seem to trickle off or to stop rather than being decisively closed. In this and in his considerable compassion for the sufferings of human beings longing for connection and to improve the lives (and, in one instance in the present volume, the appearance of their homes), Cooper reminds me of the late (great) Penelope Fitzgerald: a gay Angeleño Penelope Fitzgerald.

The most Fitzgerald-like story is “What to Name the Baby,” in which a pregnant woman takes a trip in her father’s Winnebago with his male lover (a poet always looking for the right words). The story has a lot of complications (and perhaps the most satisfying ending of any of the stories in the collection).

A leitmotif of the most developed stories is the unruly residuals of heterosexual marriages contracted by gay men trying to deny or rechannel their desires. Cooper’s life partner, sociologist and therapist Brian Miller (who in what strikes me as infantilized form appears in Truth Serum and in more fictionalized form, I think, in “Exterior Decoration”) did his dissertation (and later) research on gay fathers. I don’t know whether that research fueled any of these stories or whether Cooper’s interest in the phenomenon predated and, perhaps even facilitated, their relationship.

“Exterior Decoration” is a less than fully developed story in which a quite sick PWA undertakes beautifying the neighborhood, which includes changing porch lights on one house, painting a concrete wall of another, and a garage door of still another. Almost as mordant, funny, and sad is “Hunters and Gatherers” in which a Mormon couple (parents of six) are trying to deal with the husband’s homosexual desires. The church elders have counseled building up male bonds. Jerry, the husband, takes this as a rationale for inviting everyone gay whom he knows, including a man he sat beside on a transcontinental flight and his wife’s hair-dresser. The party for gay people who don’t know each other in a heretofore orthodoxly Mormon suburban home would be strange enough, but the attempt to meld the cultures involves giving each guest money and sending them out to get something for a potluck dinner. The guests feel sorry for the wife, the wife feels sorry for herself, and the children who escape the confinement of going to bed early are suitably perplexed about what is upsetting mommy.

My other two favorites involve the attempt of a repressed movie executive to get a man who looks like his fantasy to play the part of the scenario that plays in his head (Intro to acting) and a son who has been cut off by his father (for a fairly trivial remark) sneaking into the house after joining some Halloween trick-or-treaters (“Bit-O-Honey”). It should be obvious that Cooper has a gift for setting up complex, often absurd confrontations of expectations.

Some of the other stories deal with proto-gay children’s difficulties (“X,” “A Man in the Making”) and with adult gay males dealing with their incorrigible parents (“Between the Sheets,” “Old birds”). Each of these four stories is pointed, and they are more similar to Cooper’s earlier work (though apparently less autobiographical).

The two stories that leave me the coldest involve a gay PWA and a screwball comedy straight female friend ex-wife spying on a more recent ex-husband (“Night Sky”) and a widow who discovers her staid husband kept a record of many sexual encounters with other men (“Graphology”). Neither of these has a point or even a raison d’être I can discern and both stop rather than end. Even these two underdeveloped stories are not without interest, and some of the others are poignant and hilarious simultaneously.

published by epinions 19 June 2001

©2001, 2016, Stephen O. Murray