Meditations on a Grecian Urn

Meditations on a Grecian Urn

by B. E. J. Garmeson

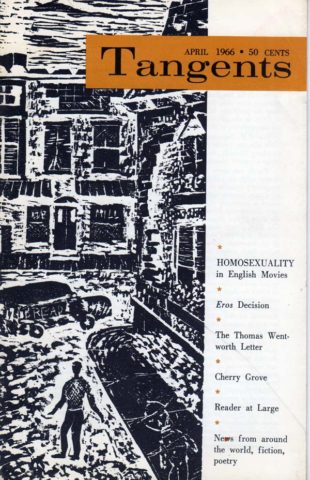

Originally published in Tangents 1.7

April 1966 • Pages 10–12

I looked sadly at the battered urn. It must have been standing outside on the terrace here for two years now, and its paint which had not been meant to take the weather, had cracked and was peeling in patches, and the graceful silhouettes of running deer faced imminent extinction. As I looked at the ruin that was all that was left of Don’s patient brushwork, I reluctantly surrendered any idea of preserving it; it was too far gone. With a sudden inexplicable anger I picked up the vase, pitched it over the wall and watched it shatter on the ground below.

Few of the things he gave me now remain. Somehow they all seem to have been fragile, accident-prone. Or is it me, perhaps? Is it my way of getting rid of memories which still disturb me, but which I cannot willingly let go?

Should one forget, I wondered? Is forgetting the secret key to a full life today forcible sundering of the ties that bind one to yesterday? Too bad, if it is, because I can’t do it. Weak, that’s me. No control over my emotions. Saying “will power” three times, diminuendo, and then falling back onto the bed laughing. I couldn’t do it the other way either, I remembered—letting jealousy and anger build up until released in a sudden flow of bitter pent-up words; furious debilitating exchanges alternating with sullen silences until the parting becomes a release instead of a torment; then, later, trading on the sympathy of friends, casting the blame, dragging down the old life into rubble on which perhaps one day a new one might he built. No, that wasn’t for me; I always thought that way out weak, too.

So you grumble, I said to myself. And there on the radio are the ashtray and candlestick they sent you for your birthday after you thought they had forgotten you. Worked yourself up into a fine tizzy of self pity over that one, didn’t you? And the sudden knee-weakening excitement when the parcel arrived at last. Surely it was undignified to care so much, to feel so deeply the need to live in the minds of an old lover and his present one.

Yet perhaps not so strange. When a lover never cheats but is honest to the last, when you like and respect a successful rival, is it not better to build friendship on the ashes of love? It has taken me nine years to get all this into some kind of perspective—four years as a lover, one year of agonizing indecision, four years of riotously peopled solitude—and I wonder if I have it right yet.

The crowded Johannesburg bar, long since handed back to the dreary beer-topers to whom it rightly belongs, was shrill with gin-slinging queens that night nine years ago. I noticed Henry seated at a table, dear old Henry, Hi. see ya. Then, as I passed, I saw Don’s face across the table from him, pale and tense. His first night in a gay bar—but a long time was to pass before I would be allowed to know that. The change, of course. Hallo, Henry, tell me all your news; how smooth and practiced it was. How lucky that Henry was a good friend, ready to push while I pulled. Poor Don, scared but not really reluctant, never stood a chance. Before he knew it, he was with me in the car, and I was pressing him urgently—come on, find us a quiet place, you know this town better than I do. For I was on holiday from Durban, four hundred miles away; we South Africans think nothing of distances you know. The competence of his directions seemed born of long experience; only long afterwards did I learn where this quiet place really was—the yard of his old school, no less! A symbol, perhaps.

Next afternoon, Sunday, was passionate, never-ending yet not long enough.

Next day I was on the road for Cape Town, a thousand miles away. For a sex carnival, this city had always been my favorite, with its numerous resorts indoors and out, and its large, cosmopolitan gay crowd. All day long I flogged the car mercilessly through the brassy glare of the Free State plains of wheat and the Karroo desert rocks shimmering with heat. Not until I arrived at the little white town of Colesberg, drowning in the purple of its enclosing hills, did I sense something amiss. How cautious was the letter I wrote that night: nice time, good fun, see you again sometime…maybe. But the reply was something else again. The English was poor, the idiom often quaint, but how I wish I had that gift for putting my whole heart into a letter. I did not read it so much as I let it speak to me with his voice, and, as soon as I could manage it, I was on the road back to Johannesburg. None of the attractions of Cape Town had power to hold me now.

That confounded urn really had me going now. Five years’ memories, all jostling each other to tap me on the shoulder and be the first to cry do you remember when, do you remember how—remember, remember, remember. It is the courtship one remembers most, of course, that, and the breaking. The years in between are apt to flow smoothly, a cornucopia of good gifts too often unappreciated.

I recalled the time when it was his turn to come on holiday, how, cautious for once, he had said he only had a week so that he would have had an easy out if things turned sour on us. And how, at the end of three, he had cried in my arms because he had to leave me. No one had ever cried over me like that before—nor since, for that matter. Somehow, something came loose inside me. In every life, I think, there are little finite points at which vital changes take place; this was one of mine.

I was still unsure, however, still cautious after my selfish worldly habit. And he, he was so loyal, certain—and ludicrously inexperienced. I came to Johannesburg for the Coronation weekend. The hotel he had chosen that afternoon for its sleepy, peaceful aspect, was, when I arrived at one in the morning, a riot. I had to nudge past two prostitutes in the hall, dodge a drunk on the stairs and step gingerly over broken glass in the passage. Small wonder that a quavering, almost tearful voice demanded positive identification before I was admitted to our room. We spent the rest of the weekend on a large divan at a friend’s house; and there, at the outset, I nearly lost out when he mistook a chill on the liver for indifference.

After that, it was plainly put up or shut up. So, after giving him many warnings about my dubious past and problematical future behavior, I put up. It was no light thing for me to take a boy, just over twenty-one away from his family and friends and carry him off some four hundred miles to a strange city and to a wholly unfamiliar way of life. But, aside fro easing my overburdened conscience, my warning and confessions served little purpose, to a Don already deeply in love.

One thing that amazes me still; the ease with which a dyed-in-the-will bachelor slipped into harness. No more stopping for drinks after work, no more making plans on my own. Always our car, our flat, our furniture. So much so, in fact, that Don had to rap me gently over the knuckles and remind me that to some people all these things were supposed to be mine and he just a lodger!

Four good shared years with Don, not by precept but just by being, teaching me the big things—how to open up to another person, what it is like to trust, safely, without reserve; how to express love without awkwardness or embarrassment, and how to accept such expressions from another. And with me teaching him little things—how to mix a cocktail, what to wear, where to go, how to behave so that one can’t be told apart from the other stuffed shirts. These things were useful, nothing more. But perhaps I gave him a few better things too—a sharing of my love of music, a sharpening of his mind with new and challenging concepts, training in analysis, reasoning, self-expression. Too, I succeeded in uprooting a few prejudices; these died hard, I must say, for once Don had taken something as his own he didn’t part with it without a struggle. I know; when at last my turn came to fight he was on my side half the time.

It’s hard to say whether it was a good thing or a bad thing that I both liked and respected James so much. Not that I had a choice—some qualities simply demand recognition. Too late, I tried to repair years of omissions; too late, I made like the prefect lover. Perhaps if I had resorted to jealous rage and flung Don out he might have been happier sooner; as it was, the three of us were condemned to miserable year of a mánage à trois. Not until the day Don turned to me for advice on how to keep James did I realize how completely I had lost.

Then came the day, as it had to come, when I stood in the hot and dusty driveway watching James back the overloaded station wagon around the corner. Don never had travelled light; the car groaned on its springs, and the luxuriant foliage of potted plants bursting from ever window made it look like a latter-day ark. The two of them had spend the night in one room, and I, never more alone in my life, another. Later, as the two of them set out on the road to Pretoria and a new life, I busied myself listlessly in that driveway making a bonfire of some of the debris of the old. Silly, useless things like the paper bags he used to take his lunch to work in took on an unlooked for significance as they turned slowly to ashes under flames invisible in the shimmering heat.

I have lived in this cottage ever since. It was just like him, in the midst of everything, to worry about where I would live after he had gone, and to work his guts out with me, paining the place out when we had found it. Now, I am going, at last, to a house of my own. These last few links—painted walls, a fresco done on the bathroom all in a last lucky moment of artistic abandon, a broken urn—will be left behind. But now I wonder why in anger I destroyed that faded, battered relic, and yet I know that it was just because if was so worn out and old as not to be a fit symbol of memories that after these years are still fresh.

I do not know whether my memories are a good thing or bad, a help or a handicap, but they are a part of me now. The things Don gave me may be fragile; these are not.

©1966, 2016 by The Tangent Group. All rights reserved.