Gerry Brissette:

Gerry Brissette:

Mattachine Momentum, Misgivings

Profile by David Hughes

Posted July 11, 2017

Introduction

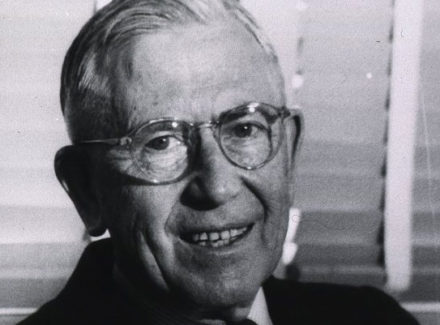

Gerard “Gerry” Brissette (November 12, 1926–September 20, 1980) almost singlehandedly organized what we now know as the Mattachine Society in the San Francisco Bay Area.

With his direction, facilitation, and participation the organization in Northern California grew from a virtually useless mailing list in mid-February 1953 to being active enough to send delegates to the Mattachine’s constitutional convention in April and May of that year. Nearly as quickly, following the conventions, Brissette became disillusioned with the organization’s trajectory and fell away. Due to a series of letters between Brissette and Mattachine cofounder Chuck Rowland in 1953, we are privy both to Brissette’s early biography as well as his motivations and challenges in building the organization in San Francisco and the East Bay. A 1976 interview of Brissette conducted by historian John D’Emilio aids in the latter regard as well.

The following is adapted from my work-in-progress with the working title The Feeble Strength of One: Bob Hull, Chuck Rowland, Maxey, Marx and the Mattachine. Because its length likely would prevent its eventual publication as-is, I offer it here.

Family Life

“I was born of a musical family in Scranton, Pennsylvania, in 1926,” Gerard “Gerry” George Brissette wrote Chuck Rowland twenty-six years later. A piano tuner-turned-life insurance salesman by trade,[1]U.S. Census, 14 Jan 1920, Wilkes-Barre, Luzerne Co., Pa., Enumeration Dist. 245, Sht. 16-A, line 44; U.S. Census, 03 May 1930, Clarks Summit Borough, Lackawanna Co., Pa., Enumeration Dist. 35-120, … Continue reading his father Albert J. also was a violinist;[2]Brissette to Rowland, 01 Mar 1953, ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives, Mattachine Society Project Collection, Box 1, Folder 9; all Brissette–Rowland correspondence referenced below is from this … Continue reading his mother Isabelle F. (Whalen) was a concert pianist.[3]Brissette’s mother’s occupation at age 16 is “Piano Player” as listed in the 1910 U.S. Census (U.S. Census, 26 April 1910, Buffalo City, Erie Co., Pa., Enumeration Dist. … Continue reading The Brissette surname had French-Canadian roots.[4]U.S. Census, 14 Jan 1920, Wilkes-Barre, Luzerne Co., Pa., Enumeration Dist. 245, Sht. 16-A, line 44. Gerry described his brother—also Albert but not Jr. (their middle initials differed)—as a “spastic.” He recalled, “When I was two […] my mother suffered a breakdown, and since then, I have never seen or heard from her.”[5]U.S. Census, 03 May 1930, Clarks Summit Borough, Lackawanna Co., Pa., Enumeration Dist. 35-120, Sht. 18-A, lines 10–13. Brissette to Rowland, 01 Mar 1953. Brissette would face his own troubles nearly two decades later.

Gerry Brissette’s parents lost three children both before and after his birth. Their son George died of myocarditis at two months of age in early 1923. (Gerry would be given George as his own middle name.) A girl was stillborn in the late summer of 1929. Another son Joseph died at five months of pneumonia from influenza in the spring of 1931.[6]Pennsylvania Department of Health Bureau of Vital Statistics Certificates of Death File Nos. 12830 (1923), 92117 (1929), 42690 (1931). It’s after this last child’s death, that his mother appears to have been institutionalized, when Gerry was not two but rather four years old.[7]Brissette’s mother is listed in Scranton’s 1932 city directory.

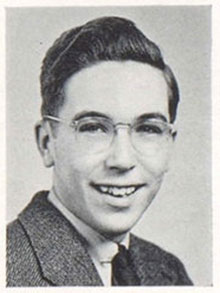

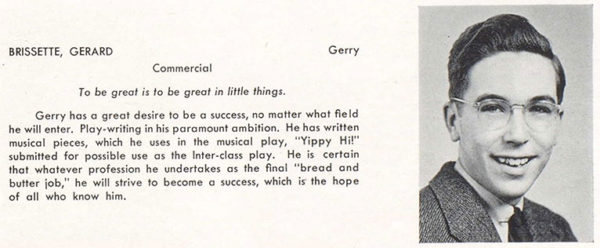

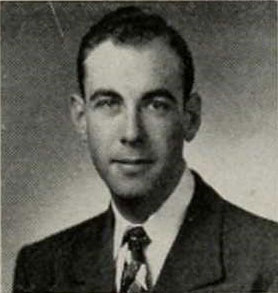

Brissette’s father last appears in the Scranton city directory in 1936. By 1940 Gerry and his father were in Queens with two lodgers from Scranton in the household. At this point, when Gerry was 13, Albert Brissette was selling pianos rather than insurance.[8]U.S. Census, 08 Apr 1940, Long Island City, Queens Co., New York, Enumeration Dist. 41-209, Sht. 5-B, lines 73–76. Gerry claimed to have been sent away not long thereafter: “The rest of my adolescence was spent in various cities in the east, living first with compassionate relatives and finally with disinterested friends, never seeming to remain any longer than two years in one spot.”[9]Brissette to Rowland, 01 Mar 1953. Nevertheless Gerry graduated from Allentown High School in Pennsylvania in 1944. He appears in the school’s Comus yearbook as a toothy, bespectacled teen in stark contrast with the two other male seniors on the page. “Play-writing in [sic] his paramount ambition,” his caption reads. “He has written musical pieces, which he uses in the musical play, ‘Yippy Hi!’ submitted for possible use as the Inter-class play.” Yet Gerry’s declared field of study was “Commercial,” indicating a path in business rather than the arts.

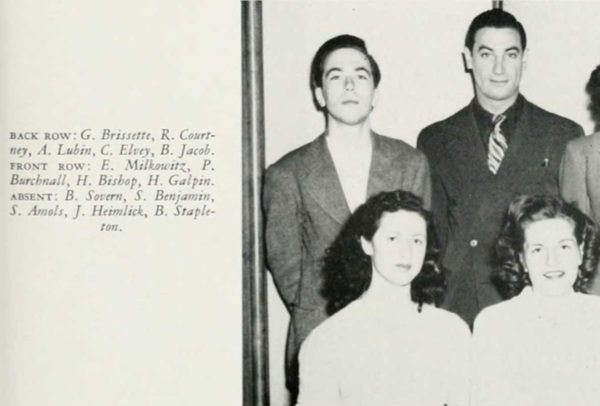

Although it’s not known if Brissette attended a full stint at the three-year Allentown High, he recalled that “after a successful high school career as a musical-comedy writer and director, an aunt in Syracuse, New York decided to send me on to the university there.”[10]Brissette to Rowland, 01 Mar 1953. Gerry’s name is absent from the lists of freshmen and sophomores pictured in the university’s 1945 and 1946 yearbooks, respectively. Even though he’s omitted from the 1946 index he is pictured that year with members of Tambourine and Bones, a theater arts honor society whose name had racist roots likely lost on honorees[11]The honor society’s name appears to reference minstrel-show stereotype characters who played the tambourine and castanets. See this image and the Wikipedia entry for Minstrel Show. and that “became active for the first time in several years” according to the yearbook—except that “T & B” had been active in the spring of ’44. Brissette directed the fall ’45 “continuity show,” Hullabaloo, just after the T & B advisor Sawyer Falk had directed a flop on Broadway.[12]Syracuse University Onondagan yearbooks for 1944–1946. While Falk’s failure could have given Brissette pause…

Although it’s not known if Brissette attended a full stint at the three-year Allentown High, he recalled that “after a successful high school career as a musical-comedy writer and director, an aunt in Syracuse, New York decided to send me on to the university there.”[10]Brissette to Rowland, 01 Mar 1953. Gerry’s name is absent from the lists of freshmen and sophomores pictured in the university’s 1945 and 1946 yearbooks, respectively. Even though he’s omitted from the 1946 index he is pictured that year with members of Tambourine and Bones, a theater arts honor society whose name had racist roots likely lost on honorees[11]The honor society’s name appears to reference minstrel-show stereotype characters who played the tambourine and castanets. See this image and the Wikipedia entry for Minstrel Show. and that “became active for the first time in several years” according to the yearbook—except that “T & B” had been active in the spring of ’44. Brissette directed the fall ’45 “continuity show,” Hullabaloo, just after the T & B advisor Sawyer Falk had directed a flop on Broadway.[12]Syracuse University Onondagan yearbooks for 1944–1946. While Falk’s failure could have given Brissette pause…

For my first two years of college, I thought of myself as God’s gift to American musical-comedy. I became president and director of Tamborine [sic] and Bones, wrote three more shows and was so encouraged by their reception that I decided to storm Broadway. After one month of haunting agents and directors, I abandoned my dream and enlisted in the army.[13]Brissette to Rowland, 01 Mar 1953.

I’ve seen Tokyo, I’ve seen France…

Brissette’s enlistment record somewhat contradicts his account of Broadway-storming. He enlisted May 14, 1946, but the university’s spring commencement was held April 28 and final exams took place at least as late as Thursday, April 25.[14]“Graduation Weekend Attracts Record Throng,” Post-Standard [Syracuse], 26 Apr 1946, 7. Even if his own finals had wrapped up by, say, Monday, April 22, he’d still have had only exactly three weeks to “storm Broadway” before enlisting on Tuesday, May 14.

Brissette had attended two years of college, according to the enlistment record, but his civilian occupation was listed as “Tinsmiths, coppersmiths, and sheet metal workers.” While he doesn’t appear to have been employed in such an occupation it’s possible he’d been advised that such a declaration would increase his chances of placement in a desirable locale.[15]No designation for Student was listed in the Civilian Occupation codes. Brissette wrote that, upon enlistment,

I became a clarinetist in a Cavalry band in Tokyo, designing variety shows, touring the bases, broadcasting twice a week over Radio Tokyo, and acting as public relations man and nursemaid for two military bands, one concert band, and three swing bands.[16]Brissette to Rowland, 01 Mar 1953.

While Brissette didn’t mention it in his letter, having seen a Tokyo half-destroyed by Allied bombing, a seed was planted regarding the wages of war, bearing fruit a few years later.

Upon discharge from the army on October 13, 1947 after exactly seventeen months[17]Beneficiary Identification Records Locator Subsystem (BIRLS) Death File. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Brissette went back to Syracuse University, “intent upon gaining a liberal education,” perhaps indicating a departure from his “commercial” pursuits of high school. “I studied everything that interested me, mostly the social sciences, English literature, Spanish, French, and German.” He graduated magna cum laude in 1949 from Syracuse. He then “went to France for a year’s study under my remaining G.I. benefits. The dream had changed, and now I wanted to write” as an expatriate. An emotional crisis caused him to return to the U.S., supported and sustained by “an old Army buddy with his wife [who] had invited me to come live with them in Berkeley.”[18]Brissette to Rowland, 01 Mar 1953. Syracuse University is identified by anonymous online interview conducted by David Hughes, July 2017.

Through these friends Brissette was introduced to the Pacific School of Religion campus and

became interested in the Quakers, pacifism, and a life of committment [sic] to God. This was the greatest step in my therapy, for here I rejoined hands with the boy I had long forgotten, the boy who had been a devout Catholic, but who had subsequently denied his faith.

My progress since then has been a slow but a steady climb to maturity and health. A home, a mate, and a work [sic] have been my aims.[19]Brissette to Rowland, 01 Mar 1953.

These aims would be fulfilled, but in a way we might not have suspected.

Mattachine Missives

In 1976, Brissette recalled to historian John D’Emilio that in about 1952 he had his first glimpse of the Mattachine, simply hearing about how the group’s founders Chuck Rowland and Harry Hay had met at a concert; being a musician himself, that factoid seems to have stuck. The next year Brissette found himself actually writing to Rowland. It seems that on Valentine’s Day 1953 Brissette attended

an orgy in Berkeley. Usually at orgies, I am reading books. I was over in the corner and [Allen] Ginsberg was wandering around bare-ass naked. Somebody slipped a letter to me that said they heard that this group was just forming in Los Angeles and I had better get in contact with them since I had expressed similar interest. I left the orgy and went home and wrote a ten-page letter to Chuck [Rowland] who was under the pseudonym [David] Freeman.[20]Interview of Gerard Brissette by John D’Emilio, 01 Nov 1976, El Cerrito, Calif. Tape 00429. International Gay Information Center collection. Audiovisual Materials, Manuscripts and Archives … Continue reading

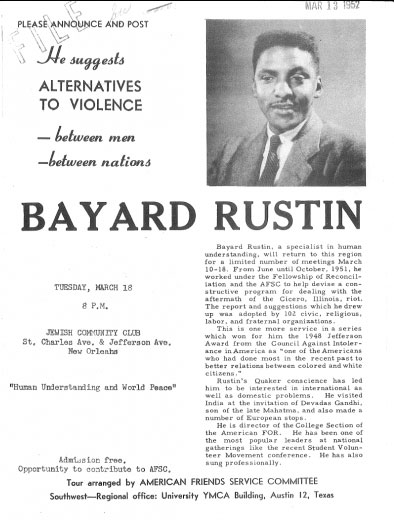

Although it may have felt to Brissette like a ten-page letter given that first contact’s impact on his life, it was in fact less than two pages, double-spaced. Dated February 15, Brissette addressed the letter to the Mattachine Foundation regarding the organization and its Citizens Committee to Outlaw Entrapment.[21]The latter is the front group that the Mattachine had formed in support of its cofounder Dale Jennings‘s legal fight regarding his own 1952 entrapment. He inquired regarding Mattachine discussion groups and whether any already had been formed in the Bay Area. He also asked about black civil rights leader Bayard Rustin’s lewd vagrancy arrest three weeks before in Pasadena. Brissette identified Rustin as being “college secretary” of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, a peace and justice organization founded by World War I pacifists and cosponsor of the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation, forerunner of the Freedom Rides of the 1960s.[22]At the time of the 1947 ride Rustin was field representative for the action’s main sponsor Congress of Racial Equality (“Direct Action Against Race Barriers Set,” Atlanta Daily … Continue reading Brissette only knew what “had reached us up here with a good deal of that Los Angeles smog,” i.e. that Rustin “had been caught in a car with two other men, but no one seems to know what they had been doing.” Knowing of the Mattachine’s work against entrapment, Brissette asked about Rustin, “Do they have incontrovertible evidence on him? Has he had a trial? If not, is there any way he can be saved? If so, has he been sent to prison?”[23]Quotes in this paragraph are from Brissette to Rowland, 15 Feb 1953. Unlike Mattachine cofounder Dale Jennings, Rustin pleaded guilty the day after his arrest, before anyone could rally ’round.[24]“Lecturer Sentenced to Jail on Morals Charge,” Los Angeles Times, 23 Jan 1953, 23.

Although it may have felt to Brissette like a ten-page letter given that first contact’s impact on his life, it was in fact less than two pages, double-spaced. Dated February 15, Brissette addressed the letter to the Mattachine Foundation regarding the organization and its Citizens Committee to Outlaw Entrapment.[21]The latter is the front group that the Mattachine had formed in support of its cofounder Dale Jennings‘s legal fight regarding his own 1952 entrapment. He inquired regarding Mattachine discussion groups and whether any already had been formed in the Bay Area. He also asked about black civil rights leader Bayard Rustin’s lewd vagrancy arrest three weeks before in Pasadena. Brissette identified Rustin as being “college secretary” of the Fellowship of Reconciliation, a peace and justice organization founded by World War I pacifists and cosponsor of the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation, forerunner of the Freedom Rides of the 1960s.[22]At the time of the 1947 ride Rustin was field representative for the action’s main sponsor Congress of Racial Equality (“Direct Action Against Race Barriers Set,” Atlanta Daily … Continue reading Brissette only knew what “had reached us up here with a good deal of that Los Angeles smog,” i.e. that Rustin “had been caught in a car with two other men, but no one seems to know what they had been doing.” Knowing of the Mattachine’s work against entrapment, Brissette asked about Rustin, “Do they have incontrovertible evidence on him? Has he had a trial? If not, is there any way he can be saved? If so, has he been sent to prison?”[23]Quotes in this paragraph are from Brissette to Rowland, 15 Feb 1953. Unlike Mattachine cofounder Dale Jennings, Rustin pleaded guilty the day after his arrest, before anyone could rally ’round.[24]“Lecturer Sentenced to Jail on Morals Charge,” Los Angeles Times, 23 Jan 1953, 23.

Replying to Brissette the Mattachine’s Chuck Rowland, writing under the pseudonym David L. Freeman, was remarkably uninformed about Rustin’s case, although its resolution had been reported in the Los Angeles Times.

We very much regret that no information has reached us on the case of Bayard Rustin, although it is the type of case we are particularly interested in. From the beginning the Mattachine Foundation has recognized the strong community of interest that must be developed among all minority groups including the homosexual. For this reason, even aside from the entrapment character of the arrest, we would be interested in doing everything possible to assist Mr. Rustin.

Our sources of information are many and highly active, but the corruption in our local Police Department (and other municipal agencies) is so vast that we know our forces are too limited to gather information on all the cases occurring daily—even many of the cases in which we would be most interested. […] We have already contacted all our key people to gather whatever information might be of value.[25]Rowland to Brissette, 23 Feb 1953.

Regarding Brissette’s query regarding a Bay Area Mattachine, Rowland also was less than helpful. “Unfortunately we do not have any organization in the Bay Area, although we plan to send some of our discussion group leaders there within the next few months,”[26]Rowland to Brissette, 23 Feb 1953. a disingenuous remark perhaps since the Mattachine leadership was preoccupied to distraction with internal dissention.

Not only was there “pressure from below” in the Mattachine, as Harry Hay told historian John D’Emilio in his own 1976 interview,[27]I am grateful to John D’Emilio for providing me with his notes from the interview, conducted 16–19 Oct 1976, San Juan Pueblo, New Mexico. there also was rancor within the leadership. Thus a Mattachine conference had been called for February.[28]I deal with this in my manuscript, referenced above. Traditionally the milestone in “pressure from below” has been seen as discussion-group reaction to Los Angeles Mirror columnist Paul … Continue reading Despite the challenges Rowland and the other Mattachine leaders faced in Los Angeles, Rowland recognized Brissette as a live wire who, if tapped, might benefit the leaders at some point, and he was not about to let Brissette go.

Of the dozens of letters we have received from the Bay Area (all enthusiastic, all highly interested), yours seems to us the most suggestive of the type of person we need—one who has the time, inclination and ability to lay the groundwork for organization there. We have on our mailing list many names of interested people whose addresses we would be happy to turn over to a competent and responsible individual. May we please hear from you further?[29]Rowland to Brissette, 23 Feb 1953.

It is this solicitation that caused Brissette to write the lengthy letter from which so many of the biographical details of his early life above are taken. In that letter Brissette also portrayed himself as a sort of urban shaman—the wounded healer—if one can express the sense behind anthropologist Joan Halifax’s 1982 title by the same name.[30]Joan Halifax. 1982. Shaman, the Wounded Healer. New York: Crossroad.

Wounded Healer

Brissette wrote that during his time in France “emotional difficulties had by now so overwhelmed me that I lost control, and in a sea of doubt, indecision, and fear I floundered.” But, as quoted above, Brissette had maintained “a slow but a steady climb to maturity and health.” As “a regular habitué of the bars and parties and travel[ing] with a circle of friends who are mostly actors, writers, and artists,” as he wrote Rowland, Brissette’s “intellectual interests seem to be chiefly centered at present around sex and the Christian experience and their integration.”

Brissette’s compassionate engagement and self-critical detachment would become evident within a couple of years. The compassionate: “Because of this, I suppose, I have come to be known as a counselor for my friends in emotional difficulties, and in many ways, one could say we have already started a discussion club on our own.” Tempered by: “I must confess to be no model of the well-adjusted invert. Certainly, I am well beyond my flaming Bohemian period”—which he did not set in time—“and when the moments of despair come, they are not as black or as prolonged as before.” The wounded healer still. And here Brissette drops a hint that he would make plain later, that

the irony of my present situation lies in my desire to be the most prolific of inverts while, were you to make a Kinseyian report, you would find me the most temperate. I search for a mate, but find instead many fine friends and still more one-night-stands. I yearn for the chance to surrender, but encounter instead situations so confused and ambiguous that only the most delicate control can maintain my equilibrium.

But I cannot live beyond my times. If I live an ambiguous life, it is because millions are living it with me. If I am confused, there is consolation in that I am not alone. I dream of freedom in a land of repression, guilt, and blue-nosed puritanism, fully realizing how impossible my dreams are when so few share them with me. To try to achieve that love by retreating behind a wall of secrecy and self-protection would be death before love ever began. For I could never build the walls high enough.

So from my failure to fulfill my dream, I gain my inspiration to change my environment. If I rebel against this ungodly pattern of “tricking” where men are not human but machines, and “camping” where life is but a joke, a game, a pit of despair, then it is my responsibility to work for the kind of world I believe in, to help create in the hearts of people like me a belief in themselves, a dignity, a capacity for loving as free men love. Only then can I ever hope to hold in my arms the happiness I pray for now. If Mattachine means this, then I am with you all the way.[31]Brissette to Rowland, 01 Mar 1953.

Brissette was twenty-six at the time. He’d seen Tokyo, he’d seen France, he’d seen many a person’s underpants. He had a dream, but one that would be fulfilled differently than he’d hoped.

Clubbing

On a practical level Brissette suggested to Rowland that he travel to Los Angeles to “see the clubs in operation, and discuss with you the many problems which you must certainly be meeting.”[32]Brissette to Rowland, 01 Mar 1953. Rowland replied enthusiastically that Brissette’s qualifications were “so entirely satisfactory” that he was embarrassed to have possibly misled Gerry into believing that a paid staff position might exist. Nevertheless he hoped Brissette could visit L.A. as soon as possible for as long as possible. Were Gerry to spend Monday through Friday there, Rowland wrote, “I’d be able to introduce you to several groups in L.A., at least one in Long Beach and one or two in Laguna Beach”—all of them different. “Some groups seem to be mainly professionals, some are working class, some Hollywood-ish […], some just ordinary people.”[33]Rowland to Brissette, 07 Mar 1953.

Brissette responded on March 11, 1953 that he’d arrive by train at 6:00 p.m. on Sunday the 15th and stay for a week.[34]Brissette to Rowland, 11 Mar 1953. “It was one of the biggest moments in my life really,” Brissette recalled. “I was scared to death.” But he was relieved upon seeing the organizers in the Union Station waiting room. “I knew immediately that they were the ones […] by the fact that they were men of such character, pride, dignity, and forcefulness.” Weeknights during his stay “I was traveling with them all of the time. We were sleeping two hours a day.” While the others did their day jobs Brissette was given his own assignments. “One of them was to write an anthem for the Mattachine Foundation.”[35]Brissette interview.

Prior to Brissette’s visit, on March 12, Los Angeles Mirror columnist Paul Coates reported on the Mattachine, fingering the Foundation’s attorney as an uncooperative witness before the House Un-American Activities Committee. The column doesn’t seem to have been a topic of much discussion during Brissette’s L.A. visit, however. Writing on March 29, Rowland told Brissette, “There has been a very considerable, delayed reaction to the Coates article. Some people are demanding the Foundation issue a ‘never have been, are not, never could be Communists…overthrow…force and violence.’ We (that is, the Foundation) has decided that there will be no statement of this sort nor [sic] or ever. […] There will be a detailed report on this subject at the Convention.” During his L.A. visit Brissette had been informed of the scheduling of the Mattachine’s first constitutional convention. “Please write as soon as you can,” Rowland wrote, “and let me know how many calls [invitations] you needs [sic] for the Convention.” Rowland and other Mattachines had been “delighted […] to have found a magnificent person like yourself to carry the Mattachine banners northward,” but had been concerned whether Brissette had achieved any success in organizing after his return from his L.A. visit.[36]Rowland to Brissette, 29 Mar 1953.

Such was the faith placed in Brissette that he was entrusted with digging up delegates upon his March 22 return to the Bay Area for a convention in L.A. only two weeks away, April 11–12—delegates from a Bay Area Mattachine that didn’t exist. If during Brissette’s visit Rowland hadn’t sensed the need for more allies, he certainly became aware during that intervening week. “The Laguna group has become very recalcitrant,” he continued on March 29. “Some of them want a loyalty oath as a condition of membership in the new Society; others may decline to attend the Convention at all,” an eventuality Rowland likely would have welcomed. Rowland confided some of his fears to Brissette: that a new Society of rank-and-filers might split from the founders’ Foundation, that a militant Society might obviate the need for a Foundation altogether.[37]Rowland to Brissette, 29 Mar 1953.

That same day, March 29, Brissette was writing Rowland. He’d made his first convert “after a beautiful act of welcome home” by “the boy” who had left a note under his cottage door. “I haven’t ceased talking about Mattachine since. The results of all this gab are three meetings this coming week: one in Berkeley, one in Oakland, and the third in San Francisco.” And the gab had form: “I have discovered that I now have a little talk of about one and a half hours long in which I explain the history of the movement, some of the successes and failures of the past, and some of the possibilities for the future.” The reactions to Brissette’s talk ranged “from horror to whole-hearted committment [sic], but little by little, I’m beginning to see the Bay area organization take shape.”[38]Brissette to Rowland, Bob [Hull], and Leon, 29 Mar 1953.

Brissette got several discussion groups started, beginning where he’d done most of his “barring”: in Oakland and in Berkeley where he lived (including a “spin-off” on the UC campus that linked up with Karl Bowman of the Langley Porter Clinic who issued his Final Report on California Sexual Deviation Research in March 1954 for the State of California). A friend in the East Bay with a place in San Francisco large enough to accommodate a gathering facilitated a group in the City. At one meeting there, Brissette recounted later,

Hal Call appeared and he had been a reporter, I guess. I will never forget it, he said at the time he was dumbfounded at what I was doing. I would just stand up and say this is what I was doing [and] this is what we’re going to do and have regular meetings, and we’re going to discuss, have social affairs, and we’re going to change society—we’re going to change the world![39]Brissette interview.

Continuing in his March 29 letter, Brissette wrote that he had a contact for a gay (yes, he used the G-word) lawyer, some psychiatrists likely would donate service, a mimeograph machine could be accessed. Strategically, “So far, I have recruited eight people from this area who want to come down to the convention,” Brissette wrote, and “I have taken great pains to explain in detail the problems and possible solutions that will face the convention” so they would be well prepared. Thus having declared himself a partisan to the old guard, Brissette signed off quickly, needing to attend to a hangover.[40]Brissette to Rowland, Bob [Hull], and Leon, 29 Mar 1953.

Canvassing the Convention

Historian James T. Sears provides much detail about the Bay Area lead-up to the Mattachine convention. “The Bay Area’s diverse leadership included Ida Bracy and her husband Paul, Trotskyite poet Jack Spicer, Harriet Stanley, a mother of six—and a former army officer, Hal Call.”[41]In my manuscript, referenced above, I discuss why characterizing Jack Spicer as a Trotskyite is not accurate. Sears also describes the Bracys as being Trotskyites. Creating a “leadership” out of those who had attended Brissette’s first meetings just days before the April convention strikes me as premature, but Sears follows, a page later, with Hal Call’s first assessment of Harry Hay. “When I met Harry Hay at the organizing convention I thought he was an erudite man way out there in the land of poetry. I didn’t think he had any practical sense about what to do with the movement.” Call saw at once that there was a movement—one to which he was very new—but one that had yet to be organized.[42]James T. Sears. 2006. Behind the Mask of the Mattachine: The Hal Call Chronicles and the Early Movement for Homosexual Emancipation, New York: Harrington Park Press, 170–173. Brissette echoed this sentiment.

Although I was interested in what Harry Hay was producing scholarly, it didn’t seem to have much validity and replicability. We couldn’t go around calling ourselves ‘berdarche’ [sic] and pretending to function like Zuni Indians. I really had objections to the whole idea that we were supposed to be jokers, that the Mattachine were clowns or the feast of fools. I didn’t like that association and objected to it…. But, we were to be called Mattachine.[43]Brissette interview.

Exactly who from the Bay Area attended the April constitutional convention of the Mattachine in Los Angeles is not certain, but Sears claims the number was nine and mentions three delegates by name: Gerry Brissette, Harriet Stanley, and Hal Call.[44]Behind the Mask, 211 n6. Brissette added Paul Bracy to that number.[45]Stanley and Bracy are mentioned as having attended by Brissette in his letter to Rowland, 19 Apr 1953.

Historian John D’Emilio writes that three key delegates—Ken Burns, Marilyn “Boopsie” Rieger, and Hal Call—had come to the conclave already looking for change. Burns was in a Los Angeles guild

whose members, one of them recalled, had been as upset by the [Mattachine Foundation’s] questionnaire to local candidates as they had been by the innuendos of Communist subversion. They felt that any open intervention in politics was “likely to destroy the organization.” Nor did they look with favor on Rowland’s and Hay’s opening speeches, which they considered rabble-rousing and radical.

Rieger was in another Los Angeles guild that, as D’Emilio writes, “remained loyal to the society’s founders and the views they espoused,” even though she had raised issues emanating from the Coates column. “However, Rieger and Burns quickly made contact at the convention and together canvassed other delegates to determine their views.” Hal Call was one likeminded delegate who “came to the convention already suspicious of the [leadership]. The keynote speeches did nothing to allay his fears. Rumors that Rowland [had been] a Communist youth organizer aroused Call’s ire, and he resolved to remove any radicals from the Mattachine.”[46]John D’Emilio. 1983. Sexual Politics, Sexual Communities: The Making of a Homosexual Minority in the United States, 1940–1970, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 78. D’Emilio’s … Continue reading

Rieger and Burns’s canvassing apparently was not subtle, as Gerry Brissette noted the week after the convention. Writing to Chuck Rowland, he said,

I wasn’t aware of it until Harriet [Stanley] began to notice that each member of our [Bay Area] delegation was being taken off into a corner for consultation. They offered us lodging and even proposed delights of the bed to win us over. They didn’t get to first base with me, but some of the more immature members of our group succombed [sic]. The result was not too bad in the long run because the real strength of our delegation was centered in Paul [Bracy] and Harriet and myself and our advice was what they eventually followed.

Brissette felt that the “small group” that was feeling out delegates “was successfully isolated for the time being.” But he was wary. “There is a danger, however, that that group, smarting under their rejection, might return to the next sessions even better organized […], and that they might seek to push through measures which will be detrimental.”[47]Brissette to Rowland, 19 Apr 1953.

At stake was the nature of the constitution. Chuck Rowland presented the draft that had gone out with the convention call, as summarized in the minutes: “A series of autonomous groups be set up in different areas with facilities to carry out any activities the groups desire […]. Area activity committees shall be set up and delegates sent from all groups to serve on these area committees.” While this summary sounds straightforward, the draft itself was vague enough to be underwhelming. The Preamble consisted of no text, but rather a definition of what a preamble should contain. Number 4 of Article I, Name and General Character, dealt with the relationship between the Mattachine Foundation and the Society, explaining what that relationship could be, again without offering a concrete proposal. These portions of the founders’ proposition came off like talking points for a Mattachine discussion group rather than a submission for up-or-down vote. Nevertheless, its horizontal approach to structure shines through, with room for autonomy.

In contrast, the alternate constitution draft was top-down, and while its authors might not have recognized it being so, I’m reminded of the shape of a typical labor union: lots of delegation, little democracy. The minutes don’t state who presented this draft, but it too was summarized:

The General Convention be the governing body of the society. The Board of Regents execute the policies of the General Convention. The Board of Regents consists of Chairman, 2 Vice Chairmen, Secty. & Treasurer. They are nominated by General Convention. A chapter in order to form must petition to the Board of Regents for a charter. Each chapter elects a Chairman, Secretary, Treasurer. They meet with equivalent officers of other chapter[s]. This constitutes the Chapter Council. The Chapter Council elects a delegate to sit on Board of Regents. Chapter Council chairmen meet with Board of Regents to give and receive information.

Only part of the constitution was discussed and voted upon; instead, a five-person interim committee was elected to “perfect” the draft and call a follow-up convention no later than May 23.[48]Details regarding the constitution come from Minutes of California State Constitutional Convention of Mattachine Society, April 11–12, 1953, ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives, Mattachine … Continue reading

Snowballing and Bombshelling

A week after the April convention Brissette wrote Rowland to complain, somewhat happily, of being overwhelmed. “It is becoming apparent to me that I am no longer pulling the group, but they are pushing me. In three weeks [sic] time, we have been able to make a sizeable dent in the consciousness of the minority here, and The Mattachine seems to be snowballing so fast that I am a little concerned that it doesn’t get out of hand.” In Oakland the regular meeting on April 13 at the Bracys’ apartment could not be contained in one room, its sixty-some attendees spilling over into the kitchen and bedroom. The reason for the overflow is evident from Brissette’s intention to have the Bay Area delegates to the April convention attend all that week’s meetings as a panel and report. Interest was even shown in the draft constitution, so much so that Brissette anticipated a series of Constitution Study Groups before the May convention.[49]Brissette to Rowland, 19 Apr 1953.

Brissette’s primary concern in the midst of this was “development of a capable, effective leadership for this area” whose participants had sprung up quickly, in contrast with the relatively leisurely development in Los Angeles.

For a whole year you met with each other in a small group and there evolved through an intimate interchange of ideas the tremendous abilities of leadership which has been the mainspring of the whole movement down south. But here we are up to here with a highly-developed philosophy, a tradition, a whole three years of experience of working with the homosexual minority tossed into our laps, so to speak. A lot of us have to grow up literally overnight.

To this end, Brissette planned to convene a leadership meeting on April 21.[50]Brissette to Rowland, 19 Apr 1953.

Chuck Rowland replied April 24, suggesting that the Bay Area leaders meet amongst themselves every two weeks as both a “group therapy” and planning session. “In this connection,” Rowland wrote, “we are talking here of the desirability of sending one or two people up there to run a kind of ‘school’ for your leadership” in about a month’s time. He considered having Wallace Maxey accompany him, given that Brissette had told him of involvement up north by professionals.[51]Rowland to Brissette, 24 Apr 1953. (Rev. Wallace de Ortega Maxey was the Foundation member who had hosted the Mattachine convention at his church.)

On April 26 Brissette reported back that he was feeling even more overwhelmed. He’d called a constitution study group on the 20th expecting perhaps a dozen; forty-five showed up. The next night, as he’d planned, Brissette held a leadership meeting at Ida Bracy’s flat, with eleven in attendance. “But unfortunately, under the influence of Paul [Bracy] and his friend, Jack Spicer, the meeting went far beyond any of my modest expectations, so that by the time the smoke cleared, the group had elected an Area Council [Pro Tem] into existence with me as its chairman.” Although Brissette felt it all was moving too fast, committees were set up, including one “to study the loyalty oath question with our lawyer.” Many ideas were in the works such as their own magazine, titled TWO.[52]The title of this prospective magazine was chosen in relationship to ONE magazine, already in publication since Jan 1953 in Los Angeles. See this timeline for ONE, Inc. the magazine’s parent … Continue reading Brissette had contacted everyone that Rowland had suggested from the Mattachine mailing list, but with no bites. “Your idea about coming up is more than just a good idea. It’s ABSOLUTELY NECESSARY that you do come and the sooner the better,” Brissette wrote. The indiscreet amongst the Bay Area newbies had given out Brissette’s last name and telephone number, leading to anonymous jail-bait calls and requests for meeting dates and times. “Some of our people are running away with the ball,” he wrote Rowland, to the point that the group might “land right smack into the hands of the Hearst press, or the police, or God knows what.” Then he dropped his bombshell. “I’ve had a girl friend for the last three years who has been a blessing and a blight upon my life for all that time. […] The terrible part about it is that I am a monogamous male by nature and fundamentally, have never really adjusted to ‘gay life’ as it exists today with all of its patterns of tricking and promiscuity.”[53]Brissette to Rowland, 26 Apr 1953. Several of Brissette’s remarks in this letter regarding the 21 Apr 1953 leadership meeting are reflected in that meeting’s minutes: Appendix I (Report … Continue reading

In a brief and admittedly “pitifully inadequate” one-page reply, Chuck Rowland ignored Brissette’s call for help, instead insisting on the restrictive conditions within which the Mattachine name could be used in the Bay Area.[54]Rowland to Brissette, 29 Apr 1953.

On April 30 Brissette asked for contact info of Wallace Maxey who Rowland had suggested could travel to the Bay Area to meet with professionals interested in the Mattachine.[55]Brissette to Rowland, 30 Apr 1953. As early as April 24 Rowland himself had suggested conducting a two-day leadership school there. “We don’t make this suggestion out of egotism or anything of the sort but rather, as you say, because we have been tried in blood and fire for three years.”[56]Rowland to Brissette, 24 Apr 1953. After wrangling over dates—having it on Mother’s Day would mean restaurant workers the Bracys would be cut out;[57]Brissette to Rowland, 30 Apr 1953. the next weekend would be the May convention[58]Rowland to Brissette, 05 May 1953.—Brissette made a desperate plea.

Chuck, even if you couldn’t have all of the leadership to all of the meetings you had planned to conduct up here, wouldn’t it still be worthwhile to come on anyway, because we are facing tremendous problems up here and I personally need much counseling? […] I’ve got to be you and Harry and Martin [Block, Mattachine publications chair] all rolled into one. […] Chuck, if nobody else needs you up here, I need you. They’ve made me mother hen and look to me as a diplomat, a ward-heeler, a spiritual mentor, and barricade lieutenant. […] By some ironic twist, I entered Mattachine to find a soulmate for myself, but in the position I am in, I have virtually cut off every last channel for a sexual outlet. Every now and then I have to stop and think that this is a HOMOSEXUAL organization I’m organizing and that I am a homosexual. Then I hear a little voice in the back of my mind saying: “What in hell’s that??” Chuck, I need you to sit down with me and answer a million questions that need to be answered IMMEDIATELY.[59]Brissette to Rowland, 06 May 1953.

Follow the Leader

Rowland held a one-day Bay Area leadership meeting on Sunday, May 17, described as a four-part discussion and lecture session on the topics of Mattachine discussion groups, movement principles, the Mattachine Foundation, and “the character of the movement.”[60]I deal with this meeting in more detail in my manuscript, referenced above. Unless otherwise cited this meeting’s particulars are taken from Special Leadership Meeting, Sunday May 17 [1953], … Continue reading Rowland played up the angle of professional participation in the Mattachine including the role of a Professional Counselling Committee, which would trawl its counselees for cases of flagrant violation of civil rights to be pursued “transcending the case of the individual himself” and which “will have a representative to study pending legislation” in Sacramento. Rowland provided too-obvious leadership tips, causing the recording secretary to preface that section of the notes with, “While well known to most people, these points were covered.” As recorded, Chuck said, “The Foundation aims to stress the need for and act as a guide to provide spiritual assistance to the homosexual minority. It places emphasis on the importance of religion in a full adjustment”—evidently aimed at any religious types like Gerry Brissette in his audience.

In that audience was Hal Call who could have taken issue with other matters advocated by Rowland: a case for clandestinity (“The secret character of the organization is ‘visionary’,” according to the notes); a case for the “show window” of the Foundation—the Mattachine’s front group; a case for admitting that “we do have a homosexual culture,” to which Call “bristled” according to his biographer Sears.[61]Behind the Mask, 108. Regarding issues of secrecy Call expressed his own counter rationale decades later to oral historian Eric Marcus:

We wanted to see Mattachine grow and spread, but we didn’t think that this could be done as long as Mattachine was a secret organization. But we knew that if we became a public organization, the FBI and other government agencies would find out about us. That was okay with us, but before we went public, we wanted to make sure that we didn’t have a person in our midst who could be revealed as a Communist and disgrace us all.[62]Eric Marcus. 1992. Making History: The Struggle for Gay and Lesbian Equal Rights, 1945–1990: An Oral History, New York: HarperCollins, 62.

May Daze

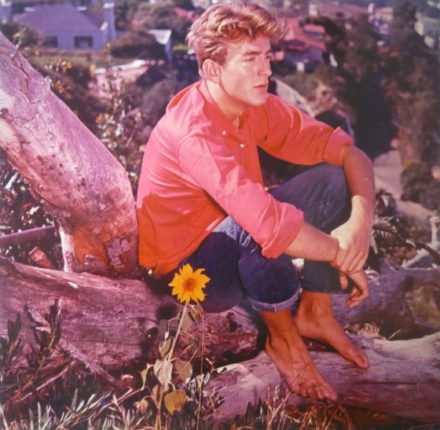

The follow-up constitutional convention was held May 23–24. The eight Bay Area delegates included a political cross-section likely as diverse and contentious as in the greater Los Angeles Mattachine. Gerry Brissette could be seen as having been part of a leftist wing that included Ida Bracy (Sears characterizes her and her husband Paul as socialists and Trotskyites[63]Behind the Mask, 199, 234.) and Jack Spicer (described as “[p]olitically an anarchist” in the finding aid to his papers at UC Berkeely). On the right, more or less, were Hal Call (already characterized above) and David Finn (described by Sears as a “voluble anticommunist” involved in the loyalty oath committee Brissette had mentioned to Chuck Rowland above[64]Behind the Mask, 208, 198.). This was rounded out by Harriet Stanley (an Oakland “mother of six”[65]Behind the Mask, 196 n2, 203.), “one unidentified person,”[66]This was Spicer’s friend Myrsam Wixman. I deal with this identification in my manuscript, referenced above. and a 19-year-old Rod McKuen,[67]Behind the Mask, 211 n6. the age of consent in California apparently having been 18 since 1913.[68]“The Explainer: What’s ‘Unlawful Sexual Intercourse’?” by Brian Palmer, Slate, 28 Sep 2009. Brissette described McKuen as having been “a very good friend of mine.”[69]Brissette interview.

The convention process had begun in April on an optimistic note, as Brissette recalled. “It was a very, very exciting time. We had a sense of pride standing up and forging a constitution like that. I can’t describe the thrill that at last we were doing something intelligent about ourselves.”[70]Brissette interview. But “the move had been a violent one to destroy the secret society and create an open one.”

By that time of the second session it became apparent to me and those who I had brought down that the process that I had observed at the first session which was vague and somewhat inarticulate[—]a good deal in the meantime had taken place to intensify the split. The big issue at the second session was whether or not the original founders would surrender the word Mattachine…. That seemed to be the most emotionally fraught issue at the time. There were meetings held over at [Rev.] Maxey’s rectory about the matter and finally consensus was reached and Chuck got up at the second session saying we will surrender the name Mattachine to this group.[71]Brissette interview, lightly edited for clarity.

“Most of us felt that we had already begun a movement,” Brissette recalled, “and that the idea of the Society”—the clandestine precursor to the above-ground Foundation—“was far too narrow” in scope compared with “the original idealism that had been generated by the original group….” Brissette and his cadre felt that such a movement would have space for “a lot of societies, eventually. And whatever dissatisfactions we might have felt” with the new Society leaders, whom the opposition saw “as Republicans or McCarthyites would fade in time.”

In this vein of continued optimism, Brissette was particularly heartened by the delegates’ decision to retain the Mattachine name. Fractious though the organization had become with the abdication of the Mattachine founders and stalwarts—Harry Hay, Chuck Rowland, and Rev. Maxey all declined nominations for office—it maintained its identity. Brissette felt the convention’s move to reject a half-dozen alternatives in favor of the Mattachine came “primarily out of a sense of Christian spirit or International spirit” of fence mending. “When the announcement was finally made a big round of applause went up and everybody was very happy there would be this continuity.”[72]All quotes above are taken from the Brissette interview, lightly edited for accuracy and clarity. Details of the convention proceedings are from Minutes of the General Convention of the Mattachine … Continue reading

Time Out

Brissette recalled two social events he organized, which took place after the May convention and before his falling away from the Mattachine in the autumn of 1953.

I had the idea of having a great big picnic with spare ribs and baked beans up at [name omitted] Park. I’d put up signs and posters around at all the bars but I had no idea how many people would show up. I had gone to the Park Rangers and told them the Mattachine Foundation was going to have a picnic. They asked how many and I said about fifty. Five hundred showed up! It was a most amusing experience because I was going with a little stick through the bushes getting rid of everybody […] because I was afraid the Park Ranger was going to come.

We had another one at Redwood Regional Park but that one exploded a little bit because some of the people who came stopped off and became very exhibitionistic and carried on around the park. [73]Brissette interview. In a letter to Brissette dated 09 Jun 1953 Ken Burns wrote, “The Los Angeles Area had a picnic last Sunday. About 50 people attended. It was a very successful picnic […]. … Continue reading

“[David] Finn voiced his opposition to the East Bay’s emphasis on social events,” according to historian James Sears. Finn wrote to the newly elected Mattachine Coordinating Council chair Ken Burns, “The groups I am organizing will have no part of this organization” if picnics and dances were “condoned.”[74]Behind the Mask, 253 n29. And when it was floated in the late summer of 1953, the “outlandish” idea of a “Mattachine-sponsored drag show in Oakland” was met with opposition by the Coordinating Council members in Los Angeles.[75]Behind the Mask, 249, 553 n30. The drag show was discussed in the 11 Sep 1953 Coordinating Council meeting, GLBT Historical Society, Donald Stewart Lucas Papers, Box 1, Folder 22. I am grateful to … Continue reading (A little more than eleven years later such an event—a private New Year’s Day Mardi Gras-themed masquerade ball—took place in San Francisco with Hal Call in attendance, as he recalled to author Paul D. Cain.)

In addition to successful extracurricular activities Brissette also seemed to have… mm… a way with the ladies.

I brought in a lot of women and they were amazed—and Chuck [Rowland] was—that I had made so many contacts with the women. I was very concerned that we make the group as equal in gender as possible. A lot of the lesbians made their contributions at that time—Ida Bracy was one and another one was [name omitted but likely Harriet Stanley based on the next sentence]. I was very proud of the role that those women took during that first [convention] session.[76]Brissette interview.

Countering Conventional Wisdom

Out of eight Mattachine Coordinating Council officers elected at the May convention Northern California was represented by Oakland’s Harriet Stanley as First Vice-Chairman and San Francisco’s David Finn as Legislative Committee Chairman. Gerry Brissette also had been nominated for Stanley’s position, but she obtained twice as many votes as Brissette and her other opponent combined. Finn ran unopposed when Harry Hay declined the nomination.[77]Minutes of the General Convention of the Mattachine Society, 23–24 May 1953, 22–25, ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives, Mattachine Society Project Collection, Box 9, Folder 22. As he does with the lead-up to the Mattachine conventions and their proceedings, historian James Sears offers much detail regarding their aftermath, which follows.

Gerry Brissette was elected Northern Area Council Chairman, Sears writes, and thus had a seat on the Coordinating Council. Hal Call was added to the area council as its recording secretary.[78]These elections were noted in Appendix IV (Area Council – Bay Cities Chapters [meeting minutes], 11 Jun 1953), Minutes of Meeting of Coordinating Council of Mattachine Society, 19 Jun 1953; and in … Continue reading The dynamic had changed now that people were assuming official leadership positions and since the loyalties had been made apparent, with Brissette and his cadre having been allied with the Foundation founders and Call and his cohort wanting a break from the past—an understandable eventuality. But Sears paints a picture of a Mattachine fractured as well by its own organizational structure, by unfortunate geographical and communicational impediments, and by a central Coordinating Council that burdened individual chapters with requirements like meeting minutes (and discussion group minutes), monetary assessments, management of volunteer-less committees, and publication of newsletters, not to mention the involvement of participants who either had no organizational experience or who didn’t see eye to eye, the latter epitomized by Brissette and Call. As Sears writes, “Paradoxically, the increase of administrative requests and additional activities […] weakened even previously strong chapters.”[79]Behind the Mask, 234–238.

Ultimately the question of autonomy of the area councils was raised, exemplified by a five-dollar charter fee for chapters, imposed by the Coordinating Council—a council essentially based in Los Angeles and “meeting two or three hours weekly at Martin Block’s Hollywood home.”[80]Behind the Mask, 231. The fee issue was raised by Jack Spicer as documented in the aforementioned Appendix IV (Area Council – Bay Cities Chapters [meeting minutes], 11 Jun 1953), Minutes of Meeting … Continue reading For its part, the Northern California area council viewed the charter fee as imposition of a taxation (along with other legislation) without representation. The Coordinating Council countered that the lines of communication were open, yet the north was not communicating with the south but rather complaining after the fact. At a Fourth of July meeting of the Coordinating Council—held in Oakland (for once)—Burns explained that, between Conventions, the Coordinating Council ruled; the next convention was set for November. Sears cites Burns as saying in that same July 4 meeting, “Under the terms of the constitution, there is no representation in the northern area because there are no chapters registered with the Coordinating Council.”[81]Behind the Mask, 239, 240. Prior to the 04 Jul 1953 meeting Burns had stated “that since we have had no formal applications for Charters from the Northern Area, the Coordinating Council must … Continue reading

Within a week the charter fees for Oakland, Berkeley, and San Francisco were paid—on July 10, 1953—by Hal Call in person in Los Angeles.[82]Behind the Mask, 245. That same month Martin Block resigned his post as the Mattachine’s publications chair, for which Brissette had been nominated at the May convention, coming in a distant third.[83]Minutes of the General Convention of the Mattachine Society, 23–24 May 1953, 25. When Block’s first and second replacements resigned by summer’s end, a new Beta Chapter in San Francisco, headed by Hal Call, volunteered to produce the Society’s publications. After all, that chapter had produced two pamphlets (authored by David Finn and Hal Call) on July 23 and the Coordinating Council had approved them for use by the Society as a whole on August 7.[84]Behind the Mask, 247–248. Call explained to author Paul D. Cain, “I helped establish a Beta Group that was concerned with creating a newsletter and starting publications.” This was in … Continue reading At some point that summer the two East Bay chapters merged and by early August this new chapter “had dwindled to a dozen.” At that same time Harriet Stanley wrote Ken Burns saying that “Oakland and that part of Berkeley who agree with them are strongly in opposition to San Francisco,” leading to a stalemate.[85]Behind the Mask, 249.

At an area council meeting on August 6, with Brissette in attendance, “Mac” ingeniously suggested that the chapters divided by the Bay reorganize as two discrete councils, with Hal Call, Jack Spicer, and “Elaine” weighing in. It was agreed that individuals and chapters be given the opportunity to realign as they wished, irrespective of the geographical boundary of the Bay. Sears states that “Gerry and Jack” led the “Oakland representation.”[86]Behind the Mask, 250. It can be inferred that Gerry was Gerry Brissette and Jack was Jack Spicer. Sears states that the meeting took place on “the evening of August 6” but he references … Continue reading Ken Burns, however, wasn’t buying it, and flew north for a September 6 meeting attended by seven each from the East Bay and San Francisco. In the meeting East Bay leaders had issues with the Society’s structure (even though some had attended the April and May conventions at which that structure was decided).[87]Sears names Ida and “Jack” Bracy by name as having critiqued the Society’s structure but Ida Bracy attended the meeting along with a John who perhaps was Jack Spicer; no one other … Continue reading Brissette and others wanted “to work quietly, at their own initiative, with a minimum of organization […] primarily for pleasure and recreation,” Sears quotes from the minutes of the September 6 meeting. Even after Burns had “endorsed” the proposed area council split in an August 28 letter to San Francisco,[88]Behind the Mask, 255–256 n53; the letter was to Joris Martin, who also attended the 06 Sep 1953 meeting as a San Francisco area member. at a 9/11 Coordinating Council meeting in Los Angeles Burns laid down the law. “Since the two chapters in the East Bay have dissolved”—a dissolution the chapters had considered a merger—”there is only officially a San Francisco Area Chapter,” he told the Council. Further, he said that “the Coordinating Council was not eliminating the East Bay Area from the Society but that they were eliminating themselves by not complying with the constitution.”[89]Behind the Mask, 250; 11 Sep 1953 Coordinating Council meeting, GLBT Historical Society, Donald Stewart Lucas Papers, Box 1, Folder 22. As noted above these minutes also contain the minutes of the … Continue reading

Twenty-some years later Brissette recalled, “I felt [the Mattachine effort] ought to be a movement, not just a little lobbying group.” Brissette recalled further that upon Burns’s election as Coordinating Council chair,

he began to insist on knowing what I was doing and was very worried that I was making contact with the churches and other social groups up here. I was acting independently and he thought it ought to be all bureaucratized and I ought to send in all the reports in triplicate and that controls ought to be placed upon me on how I was functioning as a social organizer.

Brissette added some color to the account of the September 6 meeting “where there was a big blow-up,” first by providing background, that

those who had been more of the Trotskyite affiliation wanted to seize control of the group and give it a Trotskyite International march-and-banners kind of thing. They were summarily rejected from the group or told they were not welcome. Those who had come in from the artistic, creative, church, spiritual [backgrounds] got turned off because we began to see more and more of the political kind of thing with the very straight, Brooks Brothers type […].

Regarding the September 6 meeting itself and its aftermath Brissette recalled:

The meeting I spoke of happened at Hal Call’s place. My sympathies primarily were with Jack Spicer. He was a poet and I admired him as a poet. He and I and Myrsam [Wixman], who was a friend of Jack’s, we felt there was a real division between us and this Brooks Brothers crowd. It was Jack, primarily, and his influence on me that he felt “You can take your cup of Mattachine and shove it.” I pleaded with him and said, “We need you and the kind of person you are….” We ended up driving back from that meeting and he just simply said, “I have other fish to fry and you do, too, dearie. They are going to get nowhere.”[90]All quotes above are taken from the Brissette interview, lightly edited for accuracy and clarity.

The next day was Labor Day; nonetheless, as Brissette wrote Ken Burns, “On September 7, we held a combined meeting of the East Bay Mattachines to decide on the course of future policy for this area.” The attendees “decided to retain our individual chapter charters” for Berkeley and Oakland with Brissette elected chair of the East Bay Area Council. Brissette wrote this on September 18 and continued in the letter about having attended to bureaucratic affairs such as reporting and “squaring our payments.” He wrote enthusiastically about the “tremendous task” of the Langley Porter Research Project that was to be the “principle [sic] activity of the Eastbay Area Council” and which had begun by gathering case histories. The Berkeley Study Group, wrote Brissette, had “found adequate substantiation for considering homosexual society as a ‘sub-culture’, and one of the members there is seriously considering a study of the sub-culture as the topic for her PhD thesis.” A “group therapy evening” involved “word association games and psycho-dramas” and “proved to be a very stimulating meeting,” with more to come, Brissette wrote.[91]Appendix I-4 (Brissette to Burns, 18 Sep 1953), Minutes of Coordinating Council of Mattachine Society, 30 Oct 1953, ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives, Mattachine Society Project Collection, Box … Continue reading

A subsequent Monthly Report for the combined Oakland-Berkeley Chapters for the Month of September elaborated on the Labor Day meeting, stating that it had been a session of the Policy Committee, and that all decisions regarding the formation of the East Bay Area Council “were reserved until the meeting with the Coordinating Council representatives scheduled for Sept 20”—two days after Brissette’s letter to Burns.[92]Appendix I-5 (Monthly Report for the combined Oakland-Berkeley Chapters for the Month of September), Minutes of Coordinating Council of Mattachine Society, 30 Oct 1953. At that point or shortly thereafter Brissette left the organization.

Reds and GJerrys

Minutes of an East Bay Area Council meeting held on October 20 contain: “Question of ‘Red Infiltration’ arose and decentralization urged as a means of avoiding this. General approval of a flexible organization. Decision made to organize all future programs on a social basis to be followed by the business meeting.”[93]Appendix I (Minutes of East Bay Area [Council] Meeting), Minutes of Coordinating Council of Mattachine Society, 30 Oct 1953. In other words, on a given evening, wear out the Reds in attendance so they leave, and then get down to business, thereby avoiding a takeover. This was a creative approach in line with previous policy regarding a persistent perceived problem. Just six months before, an unspecified entity of the Bay Area Mattachine had had “a mighty discussion of pro- and anti-loyalty oaths,” as Brissette had written to Chuck Rowland.

Fortunately, our leadership stands firmly upon the principle that loyalty oaths would destroy us, realizing that whether we like it or not, we’ve got to be bogged down once more, this time with an education program to all of the lower level members as to just what all this issue really means. Some girl from the Berkeley group said that she has a very fine friend who would just love to come to meetings, but refuses until the “F.B.I. investigates the whole group.” This kind of stupidity brings a laugh, but has its sobering aspects to it too.[94]Brissette to Rowland, 26 Apr 1953.

The Red question hadn’t gone away. Even had Brissette stayed on, he’d have had to face the fact that his sympathies were with anarchists like Jack Spicer and communists like the Bracys and the Mattachine founders Chuck Rowland and Harry Hay. An out-of-the-closet Mattachine evidently would not abide such characters.

As chronicled by Sears, months earlier on June 1 David Finn had written to Ken Burns that “Gerry got used to being ‘the Foundation’s only representative’ and his word was The Word.”[95]Behind the Mask, 234. That changed with the influx of the new recruits and with the Coordinating Council’s bureaucratic demands. And so Sears provides an explanation if not an excuse for Gerry’s departure from the organization he’d tried so hard to develop: “with his ‘soul mate’ boyfriend finally found,” Brissette just dropped out.[96]Behind the Mask, 251. Sears appears to attribute the “soul mate” quote to D’Emilio’s Brissette interview, but I do not find it in his transcript. As Gerry said later, “I disaffiliated with them and simply told the chapter go ahead and elect yourself a new [chair because I] have other things to do.”[97]Brissette interview. Of course, Brissette was not the chair of a chapter but rather the interim chair of the newly formed East Bay Area Council. Elect another chair they did. Brissette was replaced by one Jerry Mason as revealed in the minutes of that aforementioned October 20 East Bay Area Council meeting.[98]Appendix I, Minutes of Coordinating Council of Mattachine Society, 30 Oct 1953. Ten days later Ken Burns was pleased as punch: “Chairman remarked at the excellent organizing job the Chairman of the East Bay Area Council is doing and the Coordinating Council unanimously agreed he is to be commended on his outstanding efforts.”[99]Minutes of Coordinating Council of Mattachine Society, 30 Oct 1953. High praise, but Burns had laid it on thick with Brissette less than five months before, writing that “I believe that each time we have talked together and now that we are corresponding with each other, I have become more and more cognizant of your very excellent qualities and admire you for them.” Brissette had written Burns about his post-convention(s) concerns, to which Burns responded, “Gerry, don’t feel too badly [sic] about the reticence of some members in your Area in cooperating with the decisions of the Convention.”[100]Burns to Brissette, 09 Jun 1953. Burns needed Jerry to tow the line in October as much as he’d needed Gerry to do so in June.

Good Intentions

Over the years portrayed here Gerry Brissette engaged in his life’s experiences: as an artist in musical theater, as a musician and director and promoter in the army, as an American in Paris, eventually as a bohemian in Berkeley. Brissette’s “greatest step in his therapy,” as he’d put it—his introduction to the pacifism and doctrinal anarchism of the Quakers—was not some intellectual exercise. As I was wrapping up this profile an informant told me that Gerry “lived for a short time on a cooperative farm near Modesto,” a pacifist intentional community known as the Tuolumne Cooperative Farms.[101]The community is identified by: Iain Boal, Janferie Stone, Michael Watts, Cal Winslow, eds. 2012. West of Eden: Communes and Utopia in Northern California, Oakland: PM Press, 7. See also Patricia … Continue reading “He milked goats and delivered food to prisoners, some doing time for resisting the draft.”[102]Anonymous online interview conducted by David Hughes, July 2017. Shattered, upon his return from France Brissette had chosen more service, of this sort.

Seemingly stronger, though eventually daunted, Brissette threw himself headlong into the mission of the Mattachine. In seven short months, between February 15 and September 20, 1953 he captured—and then unleashed—the imagination of a metropolis. But his small-C catholic faith in his fellow wo/man had caused him to give the benefit of the doubt even to the likes of David Finn, a solicitude that would not be returned in kind.

I was the one who brought [Finn] into it. Someone told me at a meeting […] that he had met a most unfortunate person whose name was David Finn who was lonely and needed something like this and I, of course, never let a name go by without getting in contact. I must confess those were difficult times. I was always open, my name was in the book … but people would call me up in the middle of night and threaten me…. We, too, were visited by the vice squad…. I got a hold of [Finn] and he began to take a very aggressive role in the meetings that was very disturbing to us.

When Finn’s activities became too much to bear, Brissette “tried to cool down the reactions [Finn] was creating.”[103]All quotes above are taken from the Brissette interview, lightly edited for accuracy and clarity. For his trouble Gerry obtained Finn’s disdain. This Mattachine was a different sort of intentional community, one that had bedeviled even its founders. For what did they have in common, really, except a sexual proclivity, one that even Gerry Brissette had admitted was not either/or.

Text by David Hughes. © 2017 David Hughes. All rights reserved.