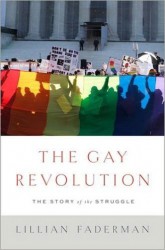

The Gay Revolution:

The Gay Revolution:

The Story of the Struggle

by Lillian Faderman

published by Simon & Schuster

Published September 8, 2015

LGBT History

816 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Billy Glover

April 30, 2016.

It is not hard to write a history of the movement to gain equal/civil rights for homosexuals.

The continuing effort began, on the record/is documented, about 1950, and early Mattachine had known founders who were still around when some historians started to acknowledge the effort.

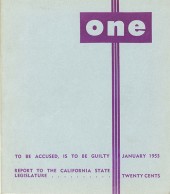

And from 1953 on, the work was documented in ONE Magazine, joined later by Mattachine Review and The Ladder, then Drum, The Advocate, etc. After 1969 certainly the general media finally started covering the effort.

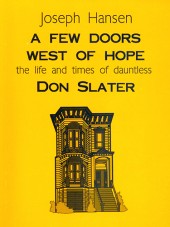

Yet the main editor of the first national homosexual movement publication, ONE Magazine, and co-founder of the organization incorporated to publish it, Don Slater, appears in Faderman’s version of history as merely an office worker under Dorr Legg.

Later, she refuses to acknowledge Slater’s co-founding of the Homosexual Information Center and only refers to him as editor of the magazine, Tangents, as if HIC did nothing else.

One part of the history Faderman ignores is our publications. She is right in that the major efforts were aimed at the evils suffered from the laws, religion, and psychiatry/the medical profession, but she ignores the educational contributions of our movement media.

She, in theory, knew of the books and magazines but ignored facts that did not fit her “views.” Proof is shown in one simple example. How could she read three books which gave correct information—Vern Bullough’s (whom she never mentions) book of short biographies of early leaders, Before Stonewall; Joseph Hansen’s (whose books and efforts, like other early glbt writers, Ann Bannon, et al., she never acknowledges) book, A Few Doors West of Hope; and C. Todd White’s book, Pre-Gay L. A.,—and make the mistake of saying that Tony’s real name was not Tony Reyes—one of the signers of the incorporation papers for ONE?

Another minor but relevant error is her attempt at giving info on our Motorcade. It seems, if I follow it, that we “started” in Echo Park, then went to Cahuenga, and then went back to Echo Park. As was covered in several places, obviously we planned and started the ride at our office on Cahuenga Blvd. West—but then she would have had to acknowledge that we had an office, with the word Tangents over the door, and we held meetings, including for college students, the L.A. Tavern Guild, GLF, etc., and had the ONE Library there, too.

Another minor but relevant error is her attempt at giving info on our Motorcade. It seems, if I follow it, that we “started” in Echo Park, then went to Cahuenga, and then went back to Echo Park. As was covered in several places, obviously we planned and started the ride at our office on Cahuenga Blvd. West—but then she would have had to acknowledge that we had an office, with the word Tangents over the door, and we held meetings, including for college students, the L.A. Tavern Guild, GLF, etc., and had the ONE Library there, too.

Faderman does, perhaps accidentally, make a point that many biased writers tried to hide—ONE was mainly a magazine for the early years, and Dorr hated that as he did not control it. Once we got money (from Reid Erickson/ISHR), he tried to gain complete control and end the magazine and push his agenda, ONE Institute, which, ironically, Faderman also ignores. That is what Dorr does deserve credit for, yet Faderman skips over all of this for the gay zaps on the East Coast.

Most of the 600 or so pages cover the recent legal victories (marriage equality, coming and going of DADT, etc)—based of course on legal efforts made earlier, starting with the ONE Magazine case, which again seems to Faderman to have been a one man effort (except for the attorney, Eric Julber), that person being Dorr, not the corporation or editor Don Slater.

Since most of the book merely covers more recent history—what the general media covered well—see the Internet—it at least gets it all in one place.

I do want to make the generic point that people seem to have chosen (and continue to choose) either Don or Dorr to “support” in the dispute that made ONE, Inc., become two organizations. And that is what Faderman does, maybe without knowing it: covers such disputes in the Daughters of Bilitis (think Gittings and Grier). The internal problems at early Mattachine were different and stemmed from the fear of the cause being harmed by its connection with communism.

Also, New York Mattachine had disputes and certainly, even though you admired him, Frank Kameny was not an easy person to work with—thank goodness he was “on our side.” It does seem, in her version of our history, that the work on the East Coast differs from the West—zaps seem more fun, if you didn’t get hurt and maybe got media coverage—but for every TV appearance there, there was one on the West Coast, and even in the Midwest.

It does seem Faderman even had a problem covering what few others have even bothered to, the Life Magazine article, with Don’s picture, but even here she merely says he is editor—and she doesn’t even mention Hal Call. Don and Dorr (and Jim Kepner, et al.) were the major workers in a corporation—the first effort in the movement to publish a magazine, start an educational institute, and to take a legal case to the U.S. Supreme Court to guarantee the right of future lgbt people to write about homosexuality.

Why is that so hard to say?

I think our cause needs a short history, and it should have a list of a few resources. But, considering the resources Faderman cites (if you take the time to see the notes and index), I do wonder why she made some, to me, important errors of facts and thus distorts the view of the effort that got us from early Mattachine to marriage equality, etc.