Gay Los Angeles: The Early Days

Essay by Jim Kepner

Gay life in Los Angeles didn’t start just yesterday — though trying to verify many early stories requires using what critics call “the evidence of the asterisk” — the evidence of recognizable omissions.

In 1781, when a band of Mexican settlers called pobladores, arrived here, the local Gabrielino Indians, who inhabited scores of villages such as Yang Na (located near what’s now Broadway and Solano) had customarily assigned, as did most native Americans, special “Berdache” roles for gay-inclined males or females, who wore clothing of the opposite gender and often took on a variety of magick [sic] social roles. Not much research has yet been done about possible gay Californios, who came from Spain and from northern Mexico, but several early accounts note that when young Antonio Lugo and his dressy friends rode their horses from their Rancho San Antonio (now the Southgate-Huntington Park-Belflower-Downey area) down to the Plaza (Olvera Street), señoritas got the flutters, But Antonio and his handsome friends weren’t interested. Antonio later led the 1848 Californio defense against the successful Yankee invasion troops led by Kearney, Stockton, Kit Carson and Fremont. Lugo later did his duty and sired many children. The only casualty of that Yankee conquest (at the Battle of San Gabriel River near Washington and Atlantic) was Lt. Ben Moore (Fort Moore, overlooking Hill Street and now housing the Department of Education, bears his name.) Moore died in the arms of his life-long intimate male companion, as most accounts noted with embarrassed formality.

Los Angeles, more than most Western towns, kept a “lawless” reputation (and until Willie Brown’s Consenting Adults Bill passed the California Legislature in 1975, all gays were included in that term, lawless) until the days which novelist Raymond Chandler wrote so well about. Gay movement founder Harry Hay, while on one of his first jobs around 1930, met two aristocratic heirs of the old Ranchero Sepulveda family, haughty gay brothers who despised each other but came in once a month to the office where Harry worked to sign legal papers. He also “met” many legendary Hollywood figures in one way or another, working some in the films himself. Like some other older gays, he reported the opening of L.A.’s first gay bar. But each older gay or lesbian I’ve talked to recalled a different bar in different years.

Maxwell’s, the Waldorf, the Brass Rail, the Biltmore, the Numbers, the Crown Jewel and other bars were popular downtown for decades, as was Jolie’s on Western at First. Bunker Hill downtown

[Page 2]

was a gay neighborhood for decades, from at least the time when Stockton’s sailors started building a fortication [sic] there in 1848 until most of the crumbling old houses on the hill were raised in the mid-’60s, as were Echo Park, Silver Lake, West Lake (I still refuse to call it MacArthur Park) where scores of handsome young men in swim trunks baked themselves on sunny afternoons, and Boyle Heights.

Many baths were largely gay, but none seemed exclusively so. Knowing attendants might size up a new customer and suggest they either go to or avoid a particular floor. There was a popular bath in Long Beach where rooftop nude sunbathing was visible, if looked fast enough, from the first big downhill rush of the giant roller coaster at the Pike Amusement center.

Long Beach, where the now demolished Pike and Ocean Blvd. were for many decades popular cruising spots, especially when the fleet was in, had a massive witch hunt against gays in 1913. Pasadena seems to have had such a witch hunt each decade. The last such virtually destroyed the prestigious Pasadena Playhouse and caused many of the elegant homes on Orange Grove to close.

World traveller Harry Otis, who danced in silent films with Theda Bara, reported gay speakeasies near Angels Flight railway, (which used to grace 3rd and Hill) and flamboyant private parties in the early Ambassador Hotel (with a fat, socially-prominent queen carried in on a palanquin by gold-draped Black “slaves,” also covered with piles of luscious fruit) hosted by the world-famed dancers Vernon and Irene Castle: also at Sid Grauman’s gala Million Dollar Theatre at 3rd and Broadway or at one of the more popular downtown baths (hosted by an early May Company big-wig). Biographies of silent film star Rudolph Valentino, whose wives were both lesbian, mention his going to gay party houses.

Houses where lesbian party were [sic] held regularly drew many top film stars, including Rambova (who built the fabulous Garden of Allah at Sunset and Crescent Heights), the Gishes, Dietrich, Minter, etc. West Hollywood, initially called Sherman, and outside the homophobic LAPD’s reach, was a gay and swinging neighborhood from the 1920s. Barney’s Beanery, once a gay bar, put up the “Fagots Stay Out” sign in the ’30s to ward off police pressure, but management and clientele later took the sign literally. Tommy Williams (who had a police permit to dress as a man) long entertained at clubs like the Footlight (where the Spike now is) and Beverly Shaw long did a sophisticated male impersonator act at the Club Laurel on Sunset, and there were other gay clubs on the strip, as well as the Garden of Allah and the Chateau Marmont, which, if not exactly gay certainly drew a large gay crowd. The Coronet Louvre film museum and Turnabout Theatre on La Cienega near Beverly were long-time centers of gay entertainment — and some very daring art shows — but were not exclusively gay. The Coronet was raided several

[Page 3]

times in the ’50s for showing such gay art films as Kenneth Anger’s Fireworks, Genet’s Un Chant D’Amour or Flaming Creatures.

An artist’s afternoon teas in the Valley were famous in the ’30s, and parties at philosophy Professor B.A.G. Fuller’s at U.S.C. or world traveller Richard Halliburton’s house in Laguna were legendary. In the mid-’20s, the music critic and medium Jesse Shepard, aka Francis Grierson, more famed from his San Diego and European days, entertained as well as his straightened finances would allow. The film star and designer William Haines, fired by movie moguls for refusing the usual public relations act of dating starlets for the fan magazine gossips, was also a famous if modest host parties and is described by many film biographies as being, with his male lover, the happiest married couple in Hollywood. There were several famous hostesses who entertained large gay crowds, from the literary Ida — to two women in the house on the southwest corner of Fountain and Wilcox, to Elsie de Wolfe. Gossip was widespread about several movie stars and directors. One occasionally saw certain ones cruising West Lake or Lafayette Parks, and we heard constantly about S&M parties which Thomas Mitchell and Charles Laughton supposedly hosted.

On July 4th, 1932, a homophobic New York gossip tabloid, Broadway BREVITIES ran a story: Depression Hits Hollywood Pansies:

In the good old days a stroll down Hollywood Boulevard was always good for a pick-up by the Margies [effeminate gays — JK] so inclined, a meal and a place to sleep by those in need, but times have changed. Today, the Pansy must keep off the famous Boulevard unless she has pennies to hand out — they are all on the make for her. Even from her famous retreats, the vast army of unemployed have deprived her of the benefits of working in peace. Pershing Square, West Lake Park, which became famous when homos found out that it was from these places that certain movie stars got their first chance for fame from ever ready directors, these places no longer offer such inducements for Miss Intermediate. [This report on the demise of Pershing Square and Westlake Park as cruising spots was premature. — JK]

Her social centers have fallen by the wayside. Muller’s, once famed for the queens in drag, has closed its doors. The Lesbian, famous the world over, who held open house every Wednesday for the ‘White Slugs,’ on the hill overlooking city jail [near 1st and Broadway — JK], has posted a NOT AT HOME sign on the “the Barn.” Flo, who held open house on Sunday and welcomed all kindred souls, even putting on a drag marriage with bride, bridesmaids and all attendants of the flower sex, economy has hit and open houses are a thing of the past. Flo must walk his six feet from home to home to meet a few of the 50,000 in L.A. and Hollywood. Even Billy, who reigned with hotel open houses that were the talk of the town from amount of liquor consumed, elaborate drags, and “how does he get away with it,” is among the “reformed.”

The Bobby L’s, who long outdid each other in elaborate parties,

[Page 4]

teas, bridges and drags, are no longer heard of along the great purple way. Mother Walker, with elaborate country weekend parties, is tending to business and has cast off social life. Even Freddie’s Sunday afternoon open house sewing bees are no longer being held. All in all, the 400 of the intermediate sex are having one heck of a time. The depression is almost more than they can stand. But a younger generation not acquainted with dirt, penny grabbers and rough trade are beginning to come to life. Perhaps a new Muller’s will open, another Lesbian reign, a new Billy, new Flo, some more Bobbies, and another Mother Walker and Freddie will start the season within a few months — they say prospects are good.

Friends who came out back then, such as the late singer and female impersonator Carol Davis, seen in the film Before Stonewall, recalled some of these 1930s Gay luminaries. Freddie, Mother Walker, Flo and Billy did indeed return to their fun-loving ways, and Carol entertained in several of Freddie’s clubs here and in other cities, while a new generation of gays happily cruised the Boulevard, as will as what was called “The Run” downtown, from the old Pacific Electric Railway Station on 6th and Main up both 5th and 6th Streets past Pershing Square and the handsome Library grounds through Book Row to the row of two-story hotels on Flower and Figueroa where rooms could be had by the hour, and on uphill to the miniature golf courses and the Evangeline Apartments for Women at 6th and Saint Paul. I lived for two years in the 40s a block further west in a half gay neighborhood then called Crown Hill.

The Big House, a lesbian club serving only fruit juice, opened briefly in Hollywood in the final years of Prohibition, but police ripped it apart, allegedly looking for liquor, because its lesbian owners refused to pay off. All bar owners were expected to pay protection to every policeman in sight. Some of its owners then ran the elegant Lake View on West 7th for a decade, (primarily lesbian, but with a fair percent of gay men and film people) getting competition later from the rougher If Club and Open Door at 7th and Vermont — beer bars where the clientele dressed down and bloody fights occurred at the drop of a hat. In 1943 there were a dozen gay bars within two blocks of where the Gay Archives was from 1979–88, starting at popular Bradleys, a cocktail lounge at the northwest corner of Hollywood and Cherokee. Hollywood was our promenade, and there was still a good chance of seeing movie stars on the street — or in the cruising spots, where many big names got into trouble which the studio publicity departments had to hush up. The Boulevard was particularly gay on Halloween and New Years. A twenty-year LAPD campaign to drive gays off the Boulevard has resulted in Hollywood’s present almost Skid-Rowish state.

The city of Santa Monica was also very gay — with crowded gay bars and baths like the Tropical Village or TV Club (where even in the ’40s, the crowd was as gay on the sidewalk as inside — something extremely rare in those closeted days), Jacks at the Beach, clubs on Channel Road, most of the homes on up the canyon and the gigantic Crystal Baths in the large pavilion immediately south of the

[Page 5]

old Marion Davies house, with three acres of gays and lesbians camping on the sand every weekend until 1957. Then a church-motivated cleanup drive overturned the city council, temporarily wiped out Muscle Beach and paved over half the beach to make parking lots, all on the pretext of “Cleaning Up Queer Alley.” This campaign was spearheaded by an Evening Outlook columnist who recanted when some gays went to his office and suggested he “find out how we really live.” He wrote a couple sympathetic columns and got fired. Several other beaches down the coast were also gay, none so much as artistic Laguna.

There were Lesbian neighborhoods from Hillhurst to Western north of Hollywood Blvd. (ONE magazine had its best sales to lesbians at the newsstand at Hollywood and Western before that became a pure porno shop), up Chevy Chase Drive in Glendale and in Culver City. Mount Washington was probably the gayest residential section in town. Central Avenue’s black clubs welcomed gays of whatever color, at a time when L.A.’s black community was concentrated into a few blocks around South Central. We were everywhere, even then, and not all of us closeted.

But closeted most of us were. Though many could be openly gay in the privacy of our bars or house parties, all but a few daring queens and dykes “pinned up our bobby pins,” and “put on the mask” once we stepped outside those doors. Even in our bars, beaches or cruising spots, we almost never talked about the subject, except in code terms. We could be guardedly open wherever there were lots of us: at the “Y,” at certain bowling alleys, women’s softball or tennis leagues, art galleries, the Bowl, ballet, Philharmonic, science fiction circles or certain metaphysical groups. One met gays and lesbians in almost any place which drew people who were “different” in one way or another. Only a few had a strong sense of group identity, but that would vanish quickly when police made a raid.

Different crowds of Gays flocked to St John’s Episcopal, Manly Palmer Hall’s, Self Realization and Vedanta, Aimee’s Foursquare Temple, First Congregational or First Unitarian, the Church at 8th and Towne where Pentecostalism got started, the Blessed Sacrament or West Hollywood Presbyterian, but we had no Church of our own until Chuck Rowland founded the short-lived Church of ONE Brotherhood in 1956. No one ever heard of gay therapists or gay realtors. Virtually all therapists were homophobic and for same sex couples to buy or occupy a house together required constant subterfuge. Trying to set up housekeeping with a person of the same sex could get one’s insurance cancelled. A few did it, but most gays believed that gay partnerships never last.

There were magazines which many of us liked, which ran half disguised gay material, but no periodicals of our own. A few little guides, such as How to Sin in Los Angeles, which listed gay spots in code, could be found on newsstands. Almost the only physique photography available was in Strength and Health, a square muscle-

[Page 6]

building magazine, or Sunshine and Health, a hetero nudist magazine, which airbrushed out anything between the legs of males who were over 14 and under 50. There were many gay novels, several of them dating to the mid ’30s, but almost all were apologetic Freudian case-studies, inevitably ending in the protagonist’s death. Most people found them hard to find, though Pickwick in Hollywood had a nice little gay section, unlabeled [sic]. We could find more in poetry: Millay, Whitman, Lawrence Hope, Walter Benton, but non-fiction other than Edward Carpenter’s was dreary and negative. Most bookstores sold gay books under the counter, or kept them in locked glass cases, and technically, the purchaser was expected to sign an affidavit that his interest in such literature was purely professional.

Gay life was fun for a few of us, if one liked subterfuge and high risk — as many gays did. “Flaunting it” then meant rubbing it in the nose of a society that was likely to turn and beat or kill you. The term “dishing” often had this same meaning. For most persons, it was fear, ostracism, self-contempt, quiet desperation and, too often, suicide. Police often stopped us on the street and asked, “Are you queer?” (I was stopped this way at least 40 times walking at night along Wilshire Blvd., near where I lived in 1943–45.) A wrong answer meant job loss (after stopping you on the street, policed often obligingly called your boss next day, asking, “Does such and such a queer work for you?), jail or worse — unless you knew and could afford one of the few attorneys who got rich fixing such cases. (Arresting officers often handed out the cards of one of these attorneys.) Going to gay bars, private parties or being seen with someone who was “obvious” was much like playing Russian Roulette — will this be the night I get busted, beaten up or blackmailed? One could be arrested just for being in a gay bar, “loitering” near a bus station or in Pershing Square, or for being on the street and looking gay. Los Angeles police alone averaged 3,000 such arrests a year, and such arrests could often result in long prison terms or being sent to mental institutions like Norwalk, Camarillo, or Atascadero, where one might be subjected to a variety of experiments from electro-shock to castration. Every time we heard a siren, we joked: “They’re coming for us!” It took me years to realize that a new generation of gays no longer knew what that “joke” meant.

The Gay Old Days were exciting for those who were very daring; but few would wish to go back.

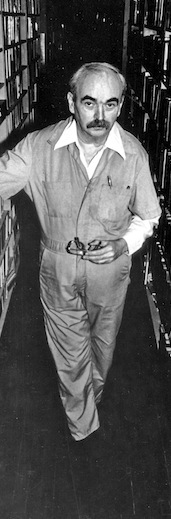

This essay was written and distributed by Jim Kepner in 1988. It is respectfully printed in his memory with minor editorial corrections. HIC is grateful to Jack Clark for providing this text.