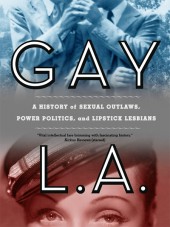

Gay L.A.: A History of Sexual Outlaws, Power Politics, and Lipstick Lesbians

Gay L.A.: A History of Sexual Outlaws, Power Politics, and Lipstick Lesbians

by Lillian Faderman and Stuart Timmons

Review and commentary by Wayne Dynes

Published by Basic Books

Published October 2, 2006

Nonfiction: LGBT history

464 pages, index

Find on Amazon.com:

Hardback • Paperback

Submitted Fall 2006

But… Why L.A.?

A half-century ago, when I sought to come to terms with my sexual orientation, things were very different. I had to reckon with the fact that, by no choice of my own, I had joined a criminal, hated minority. Advancement in my academic career required continued residence in the closet.

Now we live in a different world. Things are not perfect, of course, but we have reason to believe that full equality will not be long in coming. These changes were a national and international phenomenon.

Yet they were played out on a number of local stages. Especially in the early years, the advance of America’s gay people reflected the circumstances of particular cities. Carefully researched monographs on these places have begun to appear.

Recently, we have seen the publication of important books on gay life in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and San Francisco, among others. Los Angeles, arguably the most important center of all, has been lacking. It has had no monograph.Now that lacuna has been filled, handsomely and solidly, by Gay L.A: A History of Sexual Outlaws, Power Politics, and Lipstick Lesbians (Basic Books), co-authored by Lillian Faderman and Stuart Timmons.

Clearly written and well-documented, this book spans the history from pre-Hispanic times to the present. Unfortunately, some aspects will never be known very well, owing to the long history of persecution and obloquy. The picture becomes clearer in more recent decades. Thanks to the efforts of Faderman, the senior author, women are particularly well covered.

Los Angeles in the 1950s

By way of full disclosure, let me acknowledge that I grew up in the of the forties and fifties, the era in which the Mattachine Society made its appearance. Southern California seemed as conformist as the rest of the country, and we were astonished at the rashness of the upstarts. Many predicted that their efforts would fail. Deep-seated prejudice and the horrendous efficiency of the Police Vice Squad would see to that.

But the movement grew, and began to colonize other localities across the country. Of course there is no such thing as historical inevitability. Yet we can hazard some reasons, always acknowledging that the explanatory mechanism must remain tentative and incomplete. What follows is an attempt to capture something of the cultural ecology that fostered this development, which was revolutionary for gay people. In the following remarks I draw upon an essay I wrote ten years ago to honor Jim Kepner, one of the most tenacious and devoted of the pioneers. Let me start with the factor of place.

L.A. Demographics

In its own setting, the new style of life had a broad appeal. During the twentieth century, Los Angeles changed from a low-population desert region to a vast and complex mix of people and industries, virtually a nation to itself. Three factors made this transformation possible: a ruthless policy of water acquisition, massive real estate promotion, and a continuing advertising blitz. Lured by the advertising, unceasing waves of people flocked in by rail and car — air travel was then rare — from back East. In a single decade, from 1920 to 1930, the population of the city of Los Angeles jumped from 576,000 to 1,238,000.

As regards ethnicity the population was not homogeneous, though, it could seem so in some neighborhoods. Most of the newcomers were English-speaking Caucasians, leading to the marginalization of the Californios, the original Spanish-speaking population. Their legacy persisted mainly in certain particular features, including the names of streets like Pico and La Brea Boulevards and of districts and towns replacing the ranchos; the quaint fragment of the old Mexican pueblo known as Olvera Street; the severely functional architecture of the Franciscan missions; such literary memorials as Helen Hunt Jackson’s romantic novel Ramona (1884); and some carefully programmed ceremonies, as the movie star Leo Carrillo’s appearance on his horse.

There was much immigration from Mexico, and these newcomers settled at first mainly in East L.A., where they tended to be ignored by other Angelenos. But not always. In the forties the aggressive assertiveness of the Pachucos with their zoot suits gave notice of visibility. Although some Anglo gays began to take an erotic interest in Latins, there was generally little mixing.

A new white element appeared in the “Okie” migration, consisting of lower-class rednecks. While they could be scary, their toughness struck some of us as appealingly butch. A little later, others, like my Texas uncle Burnis, came to work in the defense factories. Attracted by similar opportunities, African Americans also came from the South. Perusal of my 1952 Yearbook from Los Angeles High School shows that considerable numbers of Jews and Armenians enlivened the initial appearance of sameness. There were also a few Japanese-American fellow students. Together with their parents, they had spent the war in the “relocation camps” situated in remote desert areas. It is fair to say, however, that the ethnic pluralism that is now the city’s chief hallmark had not yet prevailed. Yet there were big class differences. In his 1939 novel Day of the Locust, Nathanael West posed a stark contrast between sophisticated Hollywood types and the ultra-square retirees. The latter formed a large reservoir of people who were both socially and politically conservative.

For most of us growing up in those days, the Hollywood of the movies was a world apart. Distance gave rise to stereotyping and gossip. There was a general notion that a special form of decadence, including homosexuality, flourished around the edges of Hollywood. To cope with this image problem the studios undertook a pervasive self-censorship, which was reflected in the films themselves and what was reported about the stars. Defying the official version, the gay grapevine supplied some gossip. In the early 50s I was informed that Rock Hudson was gay, but I wouldn’t believe it. These queens!

The Immigrant Factor

Culturally, a major contribution stemmed from a relatively small number of émigrés from the European continent and from Britain, part of the Transatlantic Migration engendered by the rise of Hitler and the approach of World War II. After the war some of these figures, including Bertolt Brecht and Thomas Mann, went home. But many stayed, and some were openly gay. The writers Christopher Isherwood and Gerald Heard, as well as the fashion designer Rudi Gernreich, played a significant role in the emergence of the gay movement. Isherwood and Heard were drawn to the Indian mysticism of the swamis, foreshadowing the counterculture and New Age interest in Asian religions. While not many gays shared this enthusiasm, the very novelty of these systems of thought provided a model different from the Western mentality we have since come to understand as permeated with homophobia.

Born in 1949-50, the American Gay movement was not as homegrown as it seemed, for the émigrés knew about Magnus Hirschfeld and his Institute in Berlin. Alas, few of us could read German in those days, and had to rely on a few scraps gleaned in conversation.

City on the Move

Even more, perhaps, than with Hollywood, L.A. is associated with the culture of the automobile. Yet during the first half of the century the region rejoiced in a superb mass-transit system, connecting the remoter areas with the center city. But the freeways, launched just before World War II but really burgeoning only in the fifties, changed all that, forcing the streetcars out.

Thanks to suburban growth, the interstate highway system, and mass ownership of automobiles, the pattern that once seemed specific to Southern California has become increasingly characteristic of the American lifestyle everywhere. A half-century ago Los Angeles was a bellwether.

However, disastrous it may have been for the ecological balance, the shift to automobile dominance yielded certain benefits for gays. There has always been a not-so-hidden connection between the car and sex. If one didn’t have a car — and many, including my parents and myself did not — one could hitchhike. Once the driver and the hitchhiker were seated, a hand placed on the other guy’s knee was generally understood as an invitation to something more. Hustlers, young men renting their bodies, lingered alongside certain well-known boulevards and highways. Unfortunately, the police knew this too, and took advantage of the situation to entrap gays.

After having passed through a period of corruption in the early years of the century, the Los Angeles police force was reformed by proponents of good government. These centurions proclaimed themselves incorruptible. Unlike their counterparts in other cities, such as the New York to which I repaired in 1956, they generally could not be reached by bribes. Moreover, compared to the present, real crime was low in those days, and the cops had a lot of free time on their hands to plan and execute proactive strikes against “degenerates.” The repressive activity of the vice squads was a national plague that reached its height in the 1950s and ’60s. But it was particularly noxious in L.A. because of the zeal and self-righteousness of the police brass. Over the years most of my gay peers in L.A. were entrapped and arrested, requiring their presence in court with a lawyer. Getting legal representation was a considerable expense, and the publicity could devastate one’s employment prospects. In those days the vice squad was truly the serpent in Eden.

A number of suburbs of Los Angeles, such as Santa Monica and Long Beach, were separate cities — and so they have remained. The political geography of the Los Angeles basin was a patchwork quilt. It used to be said, no doubt with considerable exaggeration, that if one was going to get hit by a car, be careful not to have it happen near a civic boundary, because the ambulance drivers would leave you on the ground as they disputed over jurisdiction. This governmental pluralism offered some succor to us “deviants,” because while repression was cresting in one jurisdiction it might be absent or low in another. Until the early 1960s a number of bathhouses and bars flourished in Santa Monica, outside the LAPD’s reach. Unfortunately a local ruckus caused these places to be closed. Keeping a low profile was always advisable.

During the 1950s, California’s commitment to public education was uplifting the cultural level of the state and laying the foundations for a high-tech work force. When, in New York City in 1970, I was told that open admissions in college couldn’t work, I knew that it could. I had been a beneficiary. My experience was at the University of California at Los Angeles, where tuition, amazingly enough, was $50 a semester. The dead weight of conformist Joe-College types was relieved by the presence of many older students attending on the GI bill, together with a sizable contingent from foreign countries, especially the Middle East. UCLA also had its incipient version of a student counterculture. The Annex to the main cafeteria, which was open late, served as a gathering place for bohemians, political radicals, and gays. Those of us in the gay contingent consisted of almost equal numbers of blacks and whites. We were drawn together in part by our outcast status, but also by genuine concern for one another.

Unbeknownst to us — for the geographical dispersal the car culture entailed had its disadvantages — this salt-and-pepper tendency also characterized one of the early gay groups, the Knights of the Clock, animated by W.Dorr Legg. With the brashness of youth, those of us in the UCLA student group had a naive sense of defiance — and a false sense of security. There were shots across the bow. The dean told our most “outrageous” member, Victor S., to clean up his act or he wouldn’t graduate. About the same time a popular gay English professor was lured into making damaging statements by his department head, who tape recorded them. As was common practice in those days, tenure or not, he was summarily fired.

Interest in high culture was fairly rarified. In painting abstract expressionism was an exotic Eastern import — though it was associated in some quarters with bohemianism and social experiment. In philosophy we found inspiration in the writings of Parisian Jean-Paul Sartre, with his ideas of personal authenticity and his castigation of bad faith. Some of us, including myself, longed to settle in — or at least visit — such European countries as France and Italy, which we knew had no sodomy laws.

But popular culture was pervasive. Elvis Presley was an almost overnight phenomenon in 1955–56. According to one observer, he did a striptease without clothes. He was perhaps the first male star to come across in a way that paralleled female sex objects; today he is rightly paired with Marilyn Monroe. Presley was not gay, but his example reinforced our interest in Marlon Brando and James Dean. Dean’s gayness has only become confirmed after his death, but for many of us he was an icon. The young performer showed vulnerability — as did even more clearly his gay costar in the film Rebel Without a Cause, the slight Sal Mineo.

Venice and the Beatniks

Since the nineteenth century, the term “bohemia” has served as an umbrella term for people opting out of bourgeois norms. In southern California, the bohemian site was Venice. A real estate scheme that went sour, this beach suburb provided affordable, though flimsy housing. Many UCLA students lived there because it was cheap and connected to campus by a public bus. To mention only two people I knew, Venice was home to David McReynolds, who moved from a rather strict temperance activism to an advocacy of leftwing pacifism, and Bruce Boyd, a Beatnik poet and bonvivant. In the emerging Beatnik movement San Francisco’s North Beach and New York’s Greenwich Village ranked as the main centers. However, in 1958 Lawrence Lipton’s manifesto in book form, The Holy Barbarians, put our Venice on the map as a secondary center. Coffeehouses thrived and tour groups multiplied. For most of the fifties, however, the Beat movement was under wraps. Their numbers grew slowly — dropping out and drugs had not yet been glamorized.

Although William S. Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg were gay, and Jack Kerouac bisexual, new recruits tended to be straight. Once they got caught in the media searchlights, Beatnik men were stereotypically viewed as eunuchs, the women as nymphomaniacs. Somehow the two seemed to coalesce to have “orgies.” But Beats overlapped with gays as sociosexually subversive. And once the drug busts began, many straights got dramatic insights into what gays — and Blacks — had long had to face.

Gay Communists

Implicit in what has been mentioned is the era itself. The events could not have taken place in L.A. but for the times. In the nation as a whole, after the tremendous collaborative effort of winning World War II had achieved victory, there was a deliberate shift of emphasis. Although the 1920s slogan of a return to normalcy was not widely used, that is what the Establishment eagerly sought. At the same time there was widespread fear of a recurrence of the 1930s Depression, especially as defense industries were quickly run down. Rampant inflation and contentious strikes marred the late forties. This situation lent a certain topical vitality to the Left — though this was not to last. In 1950, however, Left thought still attracted many, especially those who had lived through the Depression when intellectuals gravitated to Communism.

Most of the founders of the original Mattachine Foundation had a Communist Party background, which was an asset organizationally (and arguably less so conceptually). Gay organizers looked to the history of Left dissidence, which had repeatedly been forced underground, as a model. The Communist example of clandestinity (a necessity in the European Resistance movements against Hitler) was a kind of dynamic closet, to coin a phrase. One could stay under cover to emerge later. Yet this furtiveness was often held against those who practiced it, lending a spurious plausibility to Senator McCarthy’s wild charges of conspiracy and subversion.

In America the postwar Left peaked in the Progressive Party, which ran Henry Wallace for president in 1948. The personality and goals of Wallace, who served as Franklin Roosevelt’s vice president in 1941–45, have always been somewhat opaque. Recent research suggests that he was guided by Theosophical mysticism, an interest that helps to explain the disconnect between him and his Left-wing following, including the gays. At all events, the Wallace candidacy was not the noble cause that gay pioneer Harry Hay and his friends thought. Although it was widely denied at the time, his fellow-traveling and Communist advisers manipulated Wallace, as the playwright Lillian Hellman, who knew the reality as few others did, has attested. With some exaggeration, socialist Irving Howe denounced the candidate as “a completely contrived creature of Stalin.” For the early gay leaders, the Communist Party background had provided training in organizational skills. It also taught one to question the normative assumptions of American society — including antihomosexual attitudes (which straight Communists, however, did not question). As times changed and insights deepened, most moved on to other political stances: New Left, Liberal, Libertarian, and even Republican. (W.Dorr Legg and Don Slater had always been Republicans.) Only a few managed to retain their earlier admiration of the Soviet Union to the bitter end.

The Cold War Era

Internationally, the fifties belonged to the era of the Cold War. Some have seen the antihomosexual bias rampant during the period as an offshoot of this conflict. This claim is too sweeping. Homophobia was not new, as it had flourished for centuries in Europe. Moreover, the repressive activities of the American vice squad had started in earlier decades, and were a manifestation of native Comstockery, that puritan impulse to control the behavior of others.

To be sure, Joseph McCarthy, the opportunistic and unprincipled Senator from Wisconsin, did link gays as “security risks” to the Communist danger. Ironically, his chief legislative assistant, the now notorious Roy Cohn, was himself gay. McCarthy’s direct influence on gay/lesbian employment and welfare was largely limited to government workers and the military. Actually, it was his attacks on the United States Army that led to his censure by the United States Senate in 1954.

The Hollywood blacklists, resulting from acquiescence in the hearings of the House Committee on Un-American Activities, deprived many of work, but apparently there were few gays among them. Yet this threat probably had a chilling effect, deterring some gays and lesbians, especially if they had leftist leanings, from seeking employment in the movie industry.

Latter-day progressives tend to interpret the “red scare” as a simple morality play, with the opponents of communism as the villains. In reality matters were more complex. The gay Whittaker Chambers, a one-time Communist turned conservative, charged Alger Hiss with transmitting information to the Soviets. Although much vilified, Chambers’ testimony helped to convict Hiss of perjury. Ever protesting his innocence, though with decreasing plausibility, the embittered Hiss (who died in 1996) could not resist the temptation to “gaybait” Chambers.

It will come as a surprise that the American Civil Liberties Union offered no help at all during this period, regarding gays who fell afoul of the law as common criminals or worse. Only in 1965, as a result of the determined efforts of Professor Vern Bullough and Attorney Herb Selwyn, did the organization’s policies regarding homosexual behavior begin to change. Ultimately the resistance to the progress of homophile rights resided in the very climate of the times. The fifties were above all the era of social conformity, of the “Lonely Crowd” to cite the title of a sociological best seller of the period.

Psychotherapists, then held in high repute, preached “adjustment.” Only in the sixties did psychiatry’s critics establish that adjustment meant regimentation and control, hardly the best foundations for human happiness. From politicians to school principals, the enforcers of conformity believed that they must hold the line even in such seemingly minor spheres as the dress and hair styles of young people. The neat and clean look of boys’ styles aped the military in World War II. Girls’ styles did not, for they had to signal a return to traditional femininity. In 1947 Christian Dior’s “new look” ushered in an era of tightly cinched waists and projecting bosoms to emphasize gender difference. Heels became higher and toes more pointed so that it became almost dangerous for women to walk. As a consequence butch lesbians who kept the wartime “Rosie the Riveter” look became more conspicuous.

In the face of these norms, very limited deviation was permitted. In my high school a few assertive boys tested the limits by allowing a tuft of hair to project at the back of the head, the “duck’s ass.” This mild infraction was considered daring and sexy.

Juvenile delinquency was a widely noted problem, but by later standards the gravity of the misbehavior — staying out late, riding fast in cars, disrespecting one’s parents — was minor, thus proving the general effectiveness of the social controls. One could only push the envelope so far. As noted above, the Beat revolt (then the proverbial dark cloud the size of a man’s hand) involved only a few individuals who garnered little media attention.

But for those who abided by the rules there were solid rewards in the form of ballooning income. We found ourselves in an enormous boom. In constant dollars the GNP grew from 1950 to 1960 from 355.3 billion to 487.7 billion, a staggering increase of 37%. The credit card appeared in 1950; supermarkets opened everywhere. Those who could went on what seemed to be a permanent spending spree. But many could not afford it. These included the elderly and most members of ethnic minorities, as well as many gays who found themselves fired for being “obvious perverts” or who restricted their own employment aspirations for fear of running into trouble of this kind or being pressured to marry. All too often, we imposed our own “glass ceiling.”

Media Influences

The carnival of consumption was accompanied by a pervasive drumbeat of inanity in popular songs, movies, and television. A popular radio program was “It Pays to Be Ignorant.” Two typical Tinpan Alley tunes were “Rudolf the Red-nosed Reindeer” and “How Much is that Doggy in the Window?” The social protest of a Bob Dylan lay in the future. In the gay bars, we searched the jukeboxes for the occasional revealing hint (or so we thought) of what the scholar Rudy Grillo has called “gay moments in straight music.”

Movies would occasionally attempt serious themes. The American film Tea and Sympathy, based on a Broadway play, dealt with gayness — up to a point — but generally one had to go to “art houses” to see imports like the British Victim, with Dirk Bogarde, and This Special Friendship, based on a boy-love novel by Roger Peyrefitte. (It was to Britain that we looked, as a matter of fact, for guidance on law reform.)

Television was new and much was expected of it. Yet what some today look back on as TV’s “Golden Age” was very bland. Television was for “family viewing,” and even hints of sexual irregularity were excluded.

Drugs were little known (as late as 1960 heroin was unfindable in L.A., though marijuana was) and even alcohol — perhaps fortunately — could be hard to come by because we had little money.

For the theme of these remarks the towering landmarks of the period were the two Kinsey Reports (1948 and 1953). Recently the figures about the incidence of homosexual behavior have been disputed, but Kinsey and his associates showed that this was vastly more common than anyone (ourselves included) had imagined. Particularly impressive was Kinsey’s nonjudgmental approach, which meant that he implicitly regarded homosexual behavior as within the normal range. I remember some daring souls who actually read passages from Kinsey aloud in Pershing Square. This small park in downtown L.A. was our equivalent of New York’s Union Square, a place for political speech that was also a cruising ground.

Typically, Pershing Square was later closed to build an underground garage, and when the mutilated park reemerged it had been sanitized so that the political and sexual activity did not return. This kind of repression of gay behavior through seemingly beneficial public works under the sign of “urban renewal” was a common device in the period. The buildings housing my two favorite bars of the fifties, the Tropical Village and the Captain’s Inn in Santa Monica, were condemned and bulldozed to make parking lots.

Things were stirring in the field of publications. Hugh Hefner founded Playboy in 1953. For a considerable time there was no gay equivalent, for ONE magazine, The Ladder, and the Mattachine Review shied away from anything explicit. At the time this was just as well, for thanks to its respectable content ONE was successful in fighting off an effort by the postmaster of Los Angeles to exclude it from the mails. This was our first Supreme Court victory.

Those in search of something more visually stimulating had to content themselves with ogling the beefcake in the popular physique magazines. Actually, this was not quite all there was. In southern California one could sometimes get pornography that had been smuggled in from Tijuana, just south of the border. These items were crudely produced. The first one I saw, in 1955, was mimeographed, but it produced quite an effect all the same. As the legal situation eased, the demand for such publications was the basis for the pulp porno industry that later emerged in San Diego and North Hollywood. During the fifties, visitors to Europe could acquire the classier publications of the Olympia Press, including the works of Henry Miller and William Burroughs. It took court decisions in the sixties to make this material available, as it now is, in every serious bookshop.

Civil Liberties

These developments in American culture helped to bring more freedom for everyone. But for gay men and lesbians there was a more rigorous and demanding model: the civil rights movement. Bayard Rustin (a closeted gay) in 1947 organized the first freedom rides. The years 1955–56 saw the Montgomery, Alabama bus boycott. This prolonged struggle garnered little white support (that was to come only later, in the 1960s). But the event, which was well reported by the media, showed that a minority could do something for itself. The city of Montgomery had tried to make boycotting illegal, but the Supreme Court affirmed it as a right. This example opened up a technique, the boycott, which has often been used by gay people, though it remains controversial.

Perhaps the most important principle affirmed by the civil rights movement was an ancient tradition going back to Pericles and Sophocles and sustained in America by Henry David Thoreau and the abolitionists. One could — and should — violate the laws on the statute books in obedience to an Unwritten Law of Justice.

Since we were few, our efforts in seeking these rights were accomplished in an atmosphere of cooperation that seems almost utopian today. Male-female relations were generally better — though my own perception of ONE’s efforts is somewhat less co-sexual than some participants now remember. Betty Friedan’s scathing critique of the “feminine mystique” had not yet energized women. Arguably women’s economic situation was worse than it became later. This was especially significant for lesbians who, faced with meager economic prospects, could be steered — coerced, really — into marriage. Later many would find the courage to dissolve these unions, bringing up the children on their own, or with a woman partner. In fact by pleading economic need two women could live together more easily then than men. Like men, they generally conformed in dress and hairstyles.

In terms of nurturing the gay movement it was (in the Dickensian phrase) the best of times, the worst of times. The war and the new car culture encouraged new patterns. Religious “kooks” made other nonconformists seem less outrageous. Conformity, however, was the watchword everywhere. As noted above, the L.A. vice squad was particularly zealous. For those who fell afoul of these repressive measures, a new determination emerged — to do something about it.

That we certainly did.