Four Trips to Cherry Grove

Four Trips to Cherry Grove

Part 1: Trips 1 and 2

by Leo MacAlbert

Tangents Vol. 1 No. 5

February 1966

Originally printed in the February 1966 issue of Tangents

pp. 26–30

TRIP 1

I called Rey at 10:15 Saturday morning.

“It’s too late,” he said.

“Let’s try,” I said.

I ran around getting ready, ran to send out my laundry, to buy color film, take the cat to the vet’s, get a present for Rey’s birthday. H. G. Wells, Outline of History—queens are big on birthday presents, sentimental.

Time passed.

No Rey.

I was getting scared. Had I loused up? Had he come by while I was out? Had he gone away? I looked down the street again and again, at each car as it came by, conscious, as I often am, of my poor eyesight and bad memory.

Finally he came in a little car, a Renault.

He had had to have his tires fixed.

We drove off.

He handed me the map. I was able to read it better than I thought. We took the 27A to Sayville, there to get the ferry. Rey was very conscious when we got to Sayville and were asking for the ferry, that we were labelling ourselves. I can’t understand this—how can you worry about strangers you’re never going to see again?

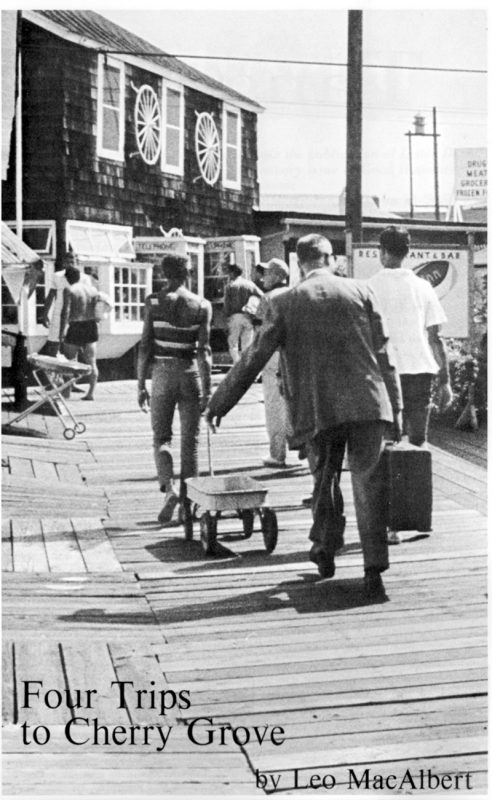

We got to the dock about 3:30. The next ferry to the Grove would be at five. I was impatient. We shared a speedboat with some other kids, obvious types, one skinny flit, one frightened faggot. We were off to the Island of Lost Boys.

The beach is big. There are about 10 streets made up of boardwalks about a yard wide, lined on both sides with bungalows, homey, simple and expensive, Villagey but more pleasant than the Village. The evening air was pleasant and briny-smelling. I was amazed at the gardens in front of the houses, some only yards from the sea—gardens using bases of pots sunk in the sand. The boardwalks form avenues, streets. There are wooden paths leading to each doorstep, and all the doors and windows were open, the houses alight.

The beach is big. There are about 10 streets made up of boardwalks about a yard wide, lined on both sides with bungalows, homey, simple and expensive, Villagey but more pleasant than the Village. The evening air was pleasant and briny-smelling. I was amazed at the gardens in front of the houses, some only yards from the sea—gardens using bases of pots sunk in the sand. The boardwalks form avenues, streets. There are wooden paths leading to each doorstep, and all the doors and windows were open, the houses alight.

A rich land, as the Good Book says.

The places had names. I wrote them on a pad. MGM [Much Gay Madness). Period of Adjustment, Miltown, Tulle Shed, Think Big, Bottoms Up, Campabello, Balbec (where Proust spent his summers), Lucky Pierre.

On the front porches of all the houses portable barbecues flamed and, often, men, white haired, were mixing martinis, something I had seen before only in movies and ads. Would I ever spend an evening like that, preparing for supper guests, mixing cocktails, affluent, assured? I couldn’t imagine it.

Now, coming toward me in the dusk, I saw Mr. X, a former fellow worker in my Welfare Center in Harlem, who recently transferred to Dykeman. How strange to see him here, so much as he was in Harlem, very thin, stiff, erect, nervous—tremendous sense of presence, like a commander with his troops, only there were no troops around.

“Oh God,” I wondered, “Is he homosexual too?”

It was like a dream. In dreams the people you meet never think it extraordinary.

He was wearing some sort of costume. Earlier I had met some one else in costume and been told he was going to a party with an Egyptian theme.

Could Mr. X get Rey and me an invitation to the party?

First he shook his head, then changed his mind. “I guess it’s all right. Just say I sent you. It’s at Manderley.”

Manderley turned out to be a place I had seen earlier, being decorated by two Negro boys with travel posters of Egypt. The party was underway when Rey and I arrived. Everyone was in costume—about one third in drag. Rey looked around in that odd, intelligent-spaniel way of his and said:

“Leo, this place is going to be raided. Let’s get out of here.”

“No,” I said, “let’s stay.”

The party was being held outside Manderley in two yards, one at the side of the house, the other in front, both separated from the outside by a fence low enough to allow people to look in. And they did look in—a great crowd of non-gay people, just standing, staring, for hours. I was amazed.

Mr. X arrived late, but without any group. With disgust he said they were taking so long to get ready, he had finally come without them. He was wearing his Pharaoh costume.

Some of the other costumes were very funny. Four boys wrapped from head to foot in gauze and wearing Beatle wigs and long, black eyelashes called themselves the Beatle Mummies. An Egyptian Queen (colored) was borne in on a litter under a big sign: EQUALITY NOW. I took off my clothes, except for my shorts, and I rolled them to a minimum.

Everyone stood around drinking punch.

I talked to the boy next to me. He was really Egyptian. Earlier be had danced for the party, doing the shakes to Beethoven’s Sixth. He was still dressed as a female belly dancer. He said he lived in Brooklyn with his mother—all these daring creatures live in Brooklyn with their families. In his house there are two phones, the family one, and his own private one which his mommie never answers. He gave me the number. With the earnestness born of alcohol, I got a piece of paper napkin and wrote it down, stuffing it into the crotch of my underwear.

“I’m staying next door,” he said. “Let’s go there for a drink.”

I told Rey I would be going out for a minute.

“Do you want the key to our room?” Rey asked.

“No,” I said, turning red.

The Egyptian belly dancer’s room was a little thing with pasteboard walls, pictures of Mickey Mouse all over them, even pictures of real mice. This kid had a thing about mice. Maybe there’s a mice shortage in Egypt.

He began kissing me, wet whiskey kisses. Where did that come from? There was only punch at the party.

“My friend is waiting for me,” I said.

We returned to the party. I had not gotten the drink.

But I soon made another acquaintance, a blond, thin boy called Ed—the number of people in the New World called Ed is very large indeed. Ed had the odd ability to carry on normal conversation while being groped—nice, if you go for normal conversation.

Yes, yes, we must meet in the city.

I talked to him about the Mattachine Society. He was interested. I was to send him the information. He gave me the address for this, then added that I was not to send his name and address to Mattachine since he sometimes lived at home and didn’t want his mother opening that kind of mail by mistake. This was the second mother-child I had met that evening, and both in their thirties! I wrote Ed’s address on a piece of silvered paper from a cigarette package and put that in my crotch—the only place in town.

It seems odd to me now that I could spend so many hours standing in a small overcrowded yard doing nothing. But apparently the costumes, drinks, hilarity, had power. Rey was high. I looked around and saw him smiling and hugging Ed, my newfound friend. I waved and smiled.

Now everyone was singing songs from Broadway shows. One queen had climbed onto the piano and was dancing. I looked beside me. Two straight boys had gotten in. They were staring sullenly at the boy on the piano. They were not singing. One of them turned to me.

“Hey, kid,” he said, “will you get me a drink?”

“There may be some punch at the table,” I said. “There’s usually some one to pour it for you—or you can dip it yourself.”

“I want you to get a drink for me,” he said.

“I’m not the host,” I said.

I turned and watched the dancing.

One of the boys turned to the other.

“Hey,” he said, let’s get some of the guys and bust the place up.”

The threat was idle since the party was guarded by the police who stood outside. They had come in earlier, but only to look through the place, to see that there was no junk, no pot, no scene going on. Still, I went and reported the boys to one of the hosts, who came back to the spot where they’d been standing. But they had gone.

Now everyone was singing “The Party’s Over,” and leaving.

As we were going out, Rey said to me, “Leo, Ed cottoned to me. He wanted to sleep with me, but I didn’t take him up on it. Didn’t want to hurt your feelings.”

“Don’t be silly,” I said, “give the boy a treat. I’ll have you some other time.”

“Do you mean it?” he said. Such an innocent boy!

“Yes,” I said.

And he ran back to the party. But Ed had left.

“Don’t worry,” I said, “you’ll see him tomorrow on the beach.”

But the morning after is not the night before. There on the beach was Ed, the Friend, but only giving us a nod, not running over. Rey, used to The Life, was not surprised, but I was shocked. Rey slept on the blanket. I walked up and down in the platinum-gold sunlight, the fresh breeze, talking to the sandpipers, bold and numerous.

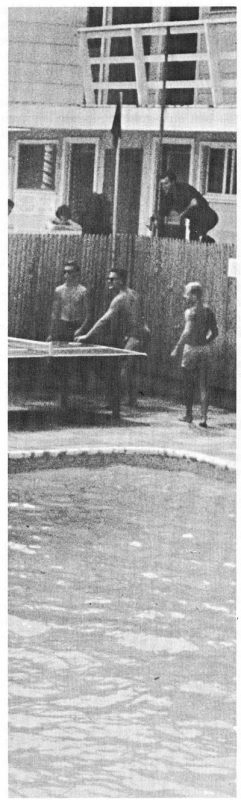

The Beach Hotel is very pleasant, a complex of small rooms on two levels, overlooking a pool in the center. Rey and I went into the dining-dancing room. The law forbids boys to dance with each other, though girls may, oddly enough. So the boys form lines and all do the same step, like a chorus. The dances they were doing, the Madison and the St. Tropez, I saw for the first time. The steps were a little intricate. Neither Rey nor I could do them at first. There were two outstanding dancers. One was a thin, wiry Negro with terrifically well-developed leg muscles.

“You a professional dancer?”

“Yes.”

The other expert was a very young Puerto Rican kid. I was unable to keep myself from introducing myself to him. He was very courteous. He told me his name. Ralph.

At the pool there was a mysterious trade magazine editor who had swum with me earlier that day. At our last parting he had explained his unshaven haggared [sic] condition with the fact that he was at a friend’s house and sharing a narrow bed. He had excused himself to get shaved. He was still unshaven.

Earlier he had told me he was drawn to me. Now he told me the same thing again. I was not superficial as so many gay boys were, he said. I told him I was incapable of any large virtue. There was so much he could do for me, he said, so many worlds he could show me.

I listened to him, treading water. He was standing at the poolside, explaining that he hated pools because they were too tame. He wanted to fight with Nature. I told him Rey and I would be back at the beach and he could meet us when he fought the sea. He went back to get shaved before he fought the sea, insisting that we must really get to know each other.

I never saw him again.

The drive back to the city in Rey’s Renault was good and easy. There were no blocks on the road. Rey told me he was very tired, that he would drive me home, drop me off, go to his own place.

When he left me, I remembered that Ed had told us he lived in my neighborhood.

I wondered if he was going on to visit Ed.

TRIP 2

On the ferry I saw a Chinese boy who had been dancing in the hotel with the wiry Negro boy and with Ralph.

“Is Ralph going to be out?” I asked him.

“He said he would be,” the boy said. “Did you see him in the city?”

“No,” I said, “I only know him from out here. If you see him, tell him I’ll be in front of the main walk, on the beach.”

But before then I saw Ralph at the hotel. Dancing. When the dance was over, he came to the edge of the dance floor and I spoke to him.

“I brought my camera. May I take your picture?”

He smiled and shook his head. Later, when Rey and I had spread our things out on the beach, Ralphie showed up. The Chinese boy had given him my message and he had come not realizing who it was he was supposed to find there. He was still so young as to imagine that the people who want to see you will be the people you want to see.

Ed was on the beach.

“What happened?” I asked him. “Why didn’t you call Rey, since you were coming out?”

“Aw, something big was breaking at the office. Then when I finally got away, I was with this girl. See, it was my birthday. I was too tied up to call.”

Do the excuses people give really seem plausible to them when they always seem so implausible to the listener? Now, Ed wanted (A) Rey’s friendship, his favors, but he didn’t want (B) to keep appointments, fulfill obligations. But the world makes (A) and (B) equal out, and Ed and myself and Rey will spend our lives trying to ignore this equation.

Rey and I had a room at The Monster, the hotel next to Jim 0’Neill’s on the path to the beach. It was called The Monster because of a carving attached to the front. But Rey called it The Dragon, maybe because he translated “monster” into Spanish and when he re-translated into English it came out “dragon.” I never found out the answer. Anyway, our room at The Monster was very nice. It had a double bed, old furniture with odd, brilliant patches of turquoise paint splattered over the sober dark wood, and great lampshades with botanical sketches on them. And the man who owned the place was kind. He bandaged my knee after I’d hurt it standing in the waves.

But we spent the afternoon by the pool at the Beach Hotel. Being with Rey was very easy, how much easier than being alone I was yet to find out. We were different. I was always jumping around. He, lazy as he was, would accommodate himself to me. When I rented chaise lounges [sic] by the pool, he stayed with me.

But we spent the afternoon by the pool at the Beach Hotel. Being with Rey was very easy, how much easier than being alone I was yet to find out. We were different. I was always jumping around. He, lazy as he was, would accommodate himself to me. When I rented chaise lounges [sic] by the pool, he stayed with me.

Ralph and his best friend and his best friend’s sister were at the pool. Often they stepped into the dance hall and danced in their bathing suits, all three of them bronzed to the same shade, their smooth, unblemished skins having the perfection of rose petals.

The lightness of the place! All the time I was there—at the Island—my one consciousness was of the tremendous amounts of light. I was unused to being out of doors, much less to being in the sun all the time. I wore sun glasses.

I had been studying my Hebrew primer and had just laid it down for a minute when a woman came past, stopped, looked at the book and picked it up. Apologizing for her curiosity, she introduced herself. She told Rey and me of her memories of the Passover Seder, the Hebrew phrases coming to her very quickly, although it had been many years since she had attended one. She laughed.

“Often the phrase, ‘Why is this night different from all other nights,’ has come to me with the most irreligious connotations.”

“Yes,” I said. “That’s happened to me too.” Ralphie was in the middle of the pool. Seeing me talking to somebody else, paying attention to somebody else, he began to make faces. I laughed.

The woman turned, glanced at Ralphie, who dived like a porpoise, and said, “Do you want me to leave? Am I bothering you?”

“No,” I said. “But I’m curious. Why are you here?”

“Why are you and your friend here?” she said.

“Because we’re fairies,” I said.

Rey, so un-fairylike, nodded in solemn agreement.

“Are you a lesbian?” I asked.

“No. But I stay here every summer. I was married. I find it less tense for me. The place has the best food on the island, the best entertainment…and I like gay boys. I think they provide a needed balance.”

A friend of hers, an older man, came over.

“Have you seen Red?” he asked.

“No,” she said.

“He’s probably off having sex somewhere,” he said, and walked away.

The ferry back was full of fairies. Somehow, I did not have the impression of this much femininity while on shore. They were twittering like teenage girls. Even the two real girls in front were behaving in a pathologically whore-like manner.

“Hello!” one of the boys said to me.

“Do I know you?” I said.

“No. but you wish you did!”

Appreciative laughter from his friends.

“Are you going to New York?” he asked me. “This girl—” and he slapped one of the girl girls on the ass, at which slap she laughed—“needs a ride.”

Universal laughter.

I looked at Rey, who shook his head.

“I’m sorry,” I said.

When we were in his car, I asked Rey why he didn’t want the girl with us.

“That kind of girl,” he said, “talks dirty, laughs in your face, doesn’t thank you, and later tells people dirty things about you. She makes me feel bad.”

An hour or so later we crossed Brooklyn Bridge to Manhattan. Overhead, groups of small birds, returning from an offshore journey, sought their homes amid the cornices of the classical building facades. Letting me out of the car, Rey said: “Next week, I’ll be leaving Friday for Atlantic City for the Miss America contest. Are you going back to the Island?”

“Don’t know,” I said.

(to be continued)

©1966, 2016 by The Tangent Group. All rights reserved.