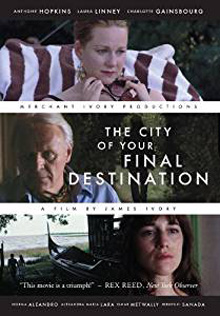

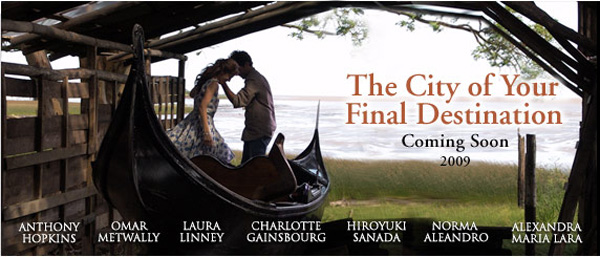

The City of Your Final Destination

The City of Your Final Destination

Directed by James Ivory

Written by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala and Peter Cameron

Released March 21, 2009 at the Golden State Film Festival

Drama (romance)

117 min.

Review by Stephen O. Murray

October 13, 2010.

Rereading my review of Peter Cameron’s novel The City of Your Final Destination after seeing the movie reassured me that Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s screenplay stayed close to the book. I also noticed that in reviewing the book, I twice mentioned E. M. Forster, which now seems to me prophetic that it would become a Merchant/Ivory film (Ismail Merchant died before shooting, but their usual screenwriter (Jhabvala) worked with director James Ivory.

The Forster novel that both the novel and the movie most reminded me of was not A Passage to India (the movie of which was directed by David Lean) but Howard’s End (the movie of which was adapted by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala and directed by James Ivory in 1992). For one thing, Anthony Hopkins played a skeptical elder for Ivory in Howard’s End, but it is the character of the earnest alien—Leonard Bast in End, Omar Razaghi in City—bumbling into dangerous contact with an extended family that most brought Howard’s End to mind, though Omar survives. (Both are bedraggled in heavy rains, too).

The movie The City of Your Final Destination is also like the 1998 Merchant Ivory film A Soldier’s Daughter Never Cries in centering on a frustrated writer and in being underappreciated by both critics and audiences.

The story of the novel

The book begins in Lawrence, Kansas and most of it is set on a property in Uruguay that is ten miles from the nearest town. To get his Jewish wife and their two sons out of Nazi Germany, Herr Gund purchased and promised to keep open an unprofitable mine in northern Uruguay. One son, Jules, wrote a novel about the pain of an adventurous flight from Europe and being plopped down in the middle of nowhere. He titled this book, the only one he published before committing suicide, The Gondola. It was at the boathouse (which is no longer on a lake, since the dam that created it collapsed) that he shot himself, and it is at the same boathouse where his would-be biographer has a life-changing experience.

Omar Razaghi, who was born in Teheran and whose physician father and family fled to Toronto when the Shah’s regime toppled, is, at the novel’s start, a graduate student at the University of Kansas with an interest in “diaspora studies.” He has a grant to write an authorized biography of Jules Gund, except that he does not have the authorization. And when he writes to request it, his request is rejected. Not only his income, but also his professional future depend on the project and his considerably more decisive girl-friend Deidre pushes him to go to Uruguay and convince the family. Omar is fairly docile and sets off—speaking no Spanish and not having a clear idea where Ochos Rios is. [It should be Ocho Rios, but perhaps it is the Gunds rather than Cameron who made the mistake…]

Omar Razaghi, who was born in Teheran and whose physician father and family fled to Toronto when the Shah’s regime toppled, is, at the novel’s start, a graduate student at the University of Kansas with an interest in “diaspora studies.” He has a grant to write an authorized biography of Jules Gund, except that he does not have the authorization. And when he writes to request it, his request is rejected. Not only his income, but also his professional future depend on the project and his considerably more decisive girl-friend Deidre pushes him to go to Uruguay and convince the family. Omar is fairly docile and sets off—speaking no Spanish and not having a clear idea where Ochos Rios is. [It should be Ocho Rios, but perhaps it is the Gunds rather than Cameron who made the mistake…]

Omar manages to get there. Arden Langdon, Jules’ mistress and mother to his one child, Portia, lives in an imitation Bavarian schloss. Also in residence is Jules’ French-born widow, Caroline. Down the road in what was a mill, Jules’ brother Adam lives with his adopted son, Pete, who had been a boy prostitute in Bangkok but was imported from Stuttgart, where Adam ran an opera house. (The only character born in Uruguay is Portia, so that the lifeways of Ochos Rios are entirely European.)

Adam recognizes that a biography might aid sales of The Gondola, thereby profiting them all. Caroline is adamantly opposed to a biography. Arden initially agrees with her, but changes her mind in part because she is impressed by Omar’s effort to get there. Also, though she has been living in the same house with Caroline for many years, being in agreement about something is a new and uncomfortable position for her.

What’s changed

Though filmed south of Buenos Aries (i.e., in Argentina) and with the great Argentine actress Norma Leandro (The Official Story), the movie continues nominally to be set in Uruguay. It includes a scene on the Rio Plata, albeit the wrong side of the river that separates Argentina and Uruguay. The house does not look Bavarian (it was built by a Scottish émigré in Argentina).

The graduate school has been moved from the University of Kansas to the more photogenic University of Colorado (though the Boulder apartment was shot in Montreal). Pete’s background has been shifted from Bangkok to a small, remote Japanese (I think Ryukyuan) island to accommodate casting of the great Japanese actor Sanada Hiroyuki, who played the urbane Japanese spy preparing for the conquest of Shanghai in the Merchant/Ivory The White Countess (and the title role in The Twilight Samurai, he was also Dogen on Lost).

The gondola is beside a river, not marooned inland. Both Omar and Deidre in the movie are able to communicate in Spanish, if a bit haltingly. There is more backstory of the emigrant Gunds (the parents of Jules and Adam, importers of the gondola, and the bases for The Condola). Adam shows Omar some home movies (culled from the archives of German Jews by Steven Spielberg and others).

I had forgotten that the titular city is New York, perhaps because the last scene in the movie is in an opera house in Madrid. Ochos Rios is an estate/house, definitely not a city or anywhere close to one. (There is an allusion to The Cherry Orchard, when Caroline makes a Manhattan for Adam.)

As is often the case in Merchant-Ivory-Jhabvala movies, there are multiple romances. Cross-cultural misunderstandings and opulent settings are also hallmarks of their movies, necessitating accolades for the set design (the two houses on Ochos Rios), Fernando Brun. The costume design, this time not “period,” is also notable. Carol Ramsey (who also clothed the casts of Slaves of New York, Mr. and Mrs. Bridge, Surviving Picasso, A Soldier’s Daughter Never Cries, and Le Divorce for Merchant-Ivory, along with Dodgeball and Meet the Fockers) went wild on the flat-chested Charlotte Gainsborough, who generally wears knee-high black boots with stylish dresses in the movie.

Performers

As the long-time gay lovers Adam and Pete, Anthony Hopkins (who turned in one of his greatest performances in the Merchant-Ivory Remains of the Day) and Sanada Hiroyuki are excellent. They are sympathetic to those living in the other house and to Omar. As the diffident, needy graduate student Omar Razaghi, Omar Metwally is fine, though considerably less impressive than he was as the victim of Rendition. He does not seem able to carry a movie as the romantic lead, though his character is supposed to be somewhat passive and dominated by his very domineering and impatient girlfriend, Deidre, who insisted he not take the trustees rejection of a biography and go to Uruguay.

In his commentary to selected scenes, Ivory says that casting Deidre was a big problem because none of the American actresses he approached want to play so unsympathetic a character. The Romania-born German actress Alexandra Maria Lara (Control, Downfall, The Baader Meinhof Complex) was not afraid of the role and makes Deidre somewhat more sympathetic than Cameron did.

Lara is especially good pitted against the other very strong woman, the widow Caroline. Reading the book, I imagined Glenn Close in the part, but Laura Linney dominates the movie as the unhappy but not self-pitying painter trapped with her husband’s mistress and child and brother. My only explanation for Linney not receiving acting award nominations for her performance is that not many saw the movie. Her situation of desperately wanting to get away is akin to that of Bette Davis in the notorious Beyond the Forest (1949). Linney’s Caroline smokes almost as much, but is less mannered than Davis (in general; Caroline’s being replaced by a younger woman echoes with Davis’s greatest role, Margo Channing (All About Eve, 1950), as does her frustration about her art).

Lara is especially good pitted against the other very strong woman, the widow Caroline. Reading the book, I imagined Glenn Close in the part, but Laura Linney dominates the movie as the unhappy but not self-pitying painter trapped with her husband’s mistress and child and brother. My only explanation for Linney not receiving acting award nominations for her performance is that not many saw the movie. Her situation of desperately wanting to get away is akin to that of Bette Davis in the notorious Beyond the Forest (1949). Linney’s Caroline smokes almost as much, but is less mannered than Davis (in general; Caroline’s being replaced by a younger woman echoes with Davis’s greatest role, Margo Channing (All About Eve, 1950), as does her frustration about her art).

Who did I picture as Arden when I was reading the book? Maybe Juliette Binoche. Arden is supposed to be French. Charlotte Gainsborough is English, but has appeared in French (The Intruder, Lemming, the Depardieu Les Misérables). Gainsborough and Metwally lack chemistry. It’s not that there is anything wrong with their performances, but the characters they are playing are indecisive and dominated by others—and the others are played by very formidable actors: Hopkins, Linney, Lara. If Arden were a strong woman, she would not be where she is…or content with there she is (and I don’t just mean geographically).

Other assets

I like the Latino-inflected score (a break from the usual wistful ones provided by Richard Robbins to Merchant-Ivory films) by Jorge Drexler (who won Oscar for his song “Al Otro Lado del Rio” in The Motorcycle Diaries), and the Poulenc sonata that Caroline plays on record, and the South American locations provide more local color than the novel had (not that it tried for that, centering on cosmopolitan German Jews in isolation on a huge estate).

Merchant Ivory films generally look great. The sets and costumes are generally praised but discounted. In City there are some deep focus shots that deserve special praise. There are fine ensemble scenes, but a number of dyadic conversations take place in terrific compositions that include outdoors from indoors and indoors from outdoors. Credit Javier Aguirresarobe. (who also shot expats in Vicky Cristina Barcelona; other credits include Talk to Her, The Sea Inside, and The Road).

The 20-minute making-of featurette and slightly longer series of comments by James Ivory are leisurely and pleasant for anyone who likes the movie. I was pleased that novelist Cameron was onscreen. Everyone involved sounds intelligent. (I twice heard of the gondola being bought online, shipped to Argentina, then to New York; Ivory has given it to Prospect Park in Brooklyn, since Central Park in Manhattan already has one. Neither time does the storyteller explain why they needed a real gondola instead of making one in Argentina.)

I guess the bottom line is intelligent, pleasant and leisurely, but not gripping.

published on epinions, 13 October 2010

©2010, 2016, Stephen O. Murray