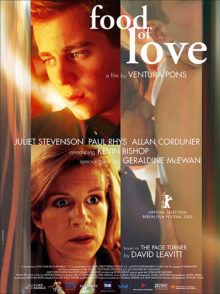

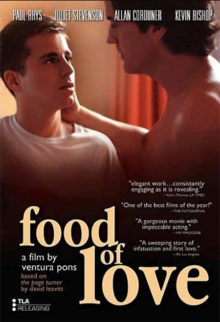

Food of Love

Food of Love

Directed by Ventura Pons

Written by David Leavitt and Ventura Pons

Released February 1, 2002 in Spain

(U.S. Premier: Utah Pride Gay and Lesbian Film Fest, January 2003)

Drama (romance)

112 min.

Review by Stephen O. Murray

June 10, 2004

I found Food of Love, the movie filmed in English in and around Barcelona by Catalán director Ventura Pons of David Leavitt’s novel The Page Turner mostly enjoyable and in some ways an improvement on the book (which I reviewed here).

I found its content less troubling than some other viewers have, but I was still troubled by one very stereotypical gay villain character and impatient (as in reading the book) for greater specificity about who did what to whom.

At the outset, it appears that the movie is about Paul (Kevin Bishop) a naive 18-year-old suburban (Menlo Park?) pianist who is going to Juilliard and is going to be the page-turner for the pianist he more or less worships. The pianist’s manager, Joseph Mansourian [Allan Corduner, who played Arthur Sullivan in Topsy-Turvy] comes on to the boy before the concert but is oddly nowhere around after, when the great pianist Richard Kennington [Paul Rhys, From Hell] invites Paul for a drink. Paul’s doting mother Pamela [Juliet Stevenson, Truly Madly Deeply, Bend It Like Beckham] is Paul’s ride home (not to mention that he is too young to drink legally), so boy and idol part.

A European trip is planned for the summer between high school and Paul’s start at Juilliard. Paul’s father (not seen in the movie at all) is having an affair and opts out of the trip. Son and mother go alone to Barcelona. Finding that he had just missed a performance by Kennington, Paul tracks him down, goes to Kennington’s hotel, and is fairly willingly seduced.

In the following days, Pamela believes that Kennington is interested in her and recovers some self-confidence, oblivious to the romance that is actually occurring between her son and a man 22 years his senior.

Who is using whom is a question that is difficult to answer here. Paul’s piano teacher [Geraldine McKewen] warned him that artists are vampires, feeding on others. Kennington seems to be feeding on Paul’s youthful vitality and unstinting admiration, but Paul is also living out a fantasy of being the beloved and protégé of a Great Artist, the particular artist he has long most admired. He also wants to feel grown-up and independent of his mother, and having a sexual relationship makes him feel grown-up, important, etc. Pamela is eager for validation, and it does not occur to her that she is being flattered to allow access to her son (which is probably not the case: Richard is being courteous rather than trying to lead her on).

It seems that she recognizes Paul’s baggy boxer shorts in Richard’s bathroom and retreats. However, at Christmas time, she is shocked to find a photo of Richard in Paul’s suitcase (along with a gay magazine and a collection of gay plays). Paul does not confide in his mother and leaves his room-mate—an also-gay Juilliard freshman from the same suburb—to field calls from her.

Fleeing Paul, Richard returns to his manager/lover, Joseph Mansourian. Paul has not seen Richard since the last evening in Barcelona when Richard panicked at Paul’s assumptions about their “relationship.” Since then (in the six month jump), Mansourian is shown oozing at a hustler. He then takes on one of Paul’s fellow Juilliard piano students, a Latin American prodigy. There is no indication that Mansourian ravishes this boy, whose success is making Paul question whether he is going to make it as a concert pianist. Mansourian hires Paul to turn pages for his fellow student, which rubs in Paul’s face the difference between his talent and the one whose talent has been noticed. Mansourian invites Paul to stay after the party. Paul knows he is going to have to put out, but he stays anyway (and pockets the photo that his mother will discover).

After a suburban conclave of mothers of gay children, the humor of which I believe is unintentional, Pamela flies to New York to save her son from being further corrupted by the man who rejected her. She arrives at the 40th birthday party Mansourian is throwing for Richard before Richard does, demanding to see her son. Mansourian puts two and two together faster than anyone else in the movie (though not before wondering whether Richard had gotten it on with Pamela rather than with Paul the previous summer).

After a suburban conclave of mothers of gay children, the humor of which I believe is unintentional, Pamela flies to New York to save her son from being further corrupted by the man who rejected her. She arrives at the 40th birthday party Mansourian is throwing for Richard before Richard does, demanding to see her son. Mansourian puts two and two together faster than anyone else in the movie (though not before wondering whether Richard had gotten it on with Pamela rather than with Paul the previous summer).

If my recounting of the plot has not made it obvious, the character who disturbs me is Joseph Mansourian. He plies a trade (artistic management) in which predation is common, and there is nothing in the movie showing any real affection Richard might have for his agent and supposed lover. Mansourian is embarrassingly abject with the hustler and is made to look vampirish, feeding on Paul’s young body (unlike Richard’s more romantic caresses). What Joe tells Richard in their final scene is chillingly dishonest.

The youth-hating, youthful-flesh-consuming monster seems drawn more from 1940s movies such as Laura [Clifton Webb as Waldo] more than from Leavitt, even if Leavitt has issues of his own with sex, particularly with intergenerational homosex. (OK, Richard is 22 years older than Paul; Mansourian and the man Paul is sleeping with look as much older than Richard as Richard is older than Paul.)

Against all odds, not least the ditziness and helplessness Pamela displayed in Barcelona, and her error in concluding that Paul and Richard were together in New York, the bottom line is that Mother Knows Best. She is over the top early on, providing some motivation for Paul’s impatience. Later on, however, Paul’s disrespect and cruelty toward her are far disproportionate to her annoyingness. It’s not just that he never extends any sympathy to her about being dumped by her husband, and ducks all her calls (even on the rare occasion he is at his apartment), but he is nasty to her far beyond any excusable adolescent quest for independence. His comeuppance is having to be told by his unworldly and despised mother that Joseph Mansourian is more than Richard Kennington’s manager.

Pamela does not save Paul from Richard’s clutches or put his career back on track. The ending leaves Paul’s future open, so that those who want to may believe she has saved him from being consumed by the needs of aging artistes and their entourage. That Pamela is able to tell Paul the story of Ganymede—and that he does not know of it until then—does not fit with anything going before the final minutes of the movie. I infer that Paul will not become immortal by connection with talent and those powerful in arts management. But whether he will continue (after the end of the movie) to orbit bigger talents is uncertain. Probably some viewers will conclude that Pamela has saved her son from homosexuality (building on the repugnance for letting Joseph Mansourian go down on him that Paul shows while the deed is being done).

In that I made a point of it in reviewing the book, I should mention that I found Paul’s realization that he is not going to become a star performer more credible in the movie than in the book. In the movie, it builds, instead of being a Eureka! flash of insight. I’ve come around to accepting that such a realization may come all at once (as Cindy maintained in commenting on my review of the novel), but Paul’s insights in general develop gradually, not in lightning flashes, and the development of his doubt that he has what it takes (in talent and in ambition… and in ruthlessness) is well portrayed in the movie.

My favorite star in the movie is the city of Barcelona, much loved by director Pons who only makes movies there. It’s hard to like Paul or Richard. Pamela is hard to take until her rally to wisdom at the end, though it is difficult not to feel sympathetic for her given her son’s nastiness and her diffidence. And Joseph Mansourian’s character makes me shudder. Although he has some of the same fears Pamela has, he is vicious far beyond Paul’s capacity to comprehend, let alone any to perform: Paul is more petulant than villainous.

I don’t find Paul Rhys attractive, and am glad that most of the nudity involves the attractive Kevin Bishop. Although he is not the most beautiful boy in the world, as Ganymede was, he has a nicely shaped derrière (displayed in four different scenes; there is no frontal nudity in the movie). He looks older than 18, and, in fact, was 22 when the movie was released in 2002. Some have complained about his stiffness (not Joseph Mansourian, though!!). I think that some gawkiness is required for the part of Paul. Bishop sounds American—as Rhys never does (Stevenson and Corduner nearly manage to sound American). In the bonus-track interviews with the principal actors, Bishop sounds the most British, and I think he deserves more praise than he has received for his acting in Food for Love.

The actor interviews are interesting, as is the lengthy interview with David Leavitt (that includes the questions, often long and stilted ones). The interview of Pons (which, like those of the actors, deletes the question, making for considerable jerkiness as the viewer reconstructs what the question must have been) is boilerplate praise for everyone involved in making the movie, and it inadvertently provides reassurance that a commentary track from the director would add very little.

The only regret that David Leavitt expresses about the movie is that there wasn’t more music. I thought there was the right amount of classical music and that the movie soundtrack of “original” music was fine. I feel sorry for the composer having to provide music that is juxtaposed to performances of the music of Brahms, Chopin, Scarlatti, Schubert, and others. Not surprisingly, he is not in their league. (Perhaps he could turn the pages for them?) There are some problems with the audio transfer just over an hour in.

There are also trailers for six movies, including this one (quoting the Ganymede story, BTW).

Pros: Barcelona, Kevin Bishop, Juliet Stevenson, actor and writer interviews

Cons: the stereotypical viciousness of Joseph Mansourian’s part

The Bottom Line: May frighten some.

©10 June 2004, Stephen O. Murray