Flagrant Conduct

The Story of Lawrence v. Texas:

How a Bedroom Arrest Decriminalized Gay Americans

by Dale Carpenter

Published by W. W. Norton & Company

Published March 12, 2002

History (law)

368 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Review by Stephen O. Murray

April 5, 2012

Flagrant Conduct: The Story of Lawrence v. Texas, published in 2012 by University of Minnesota law professor Dale Carpenter (1966– )[1]he has since moved to Emory University, is the most absorbing and is already becoming the most-read book about a Supreme Court decision since Anthony Lewis’s Gideon’s Trumpet[2] A history about Clarence E. Gideon v. Louie L. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335 (1963), in which the court unanimously affirmed the right of defendants to legal counsel in state court criminal proceedings., most of which first appeared in the New Yorker in 1964 then as a book.

The story of the case[3]John Geddes Lawrence and Tyron Garner v Texas 539 U.S. 558 (2003) that led to a 6–3 decision ruling the sodomy laws has a large and remarkably disparate cast of characters, most of whom Carpenter persuaded to talk to him and all of whom he deftly sketches.

There is “flagrant conduct,” though in my view that characterizes Justice Antonin Scalia and the first (therefore lead) of the four Harris County (metro Houston) sheriff’s deputies in John Lawrence’s apartment on the night of 17 September 1998 and the man Robert Royce Eubanks who made a call (for which he later served jail time for making a false police report) that a “n__gg_r with a gun” was “going crazy” in the apartment.

There was no gun, at least until the four Harris County deputies drew theirs inside the apartment, where they first confronted a man in the kitchen.

To put it mildly, there is more than reasonable doubt not only about whether sex was going on, and, if so, whether it was oral or anal, but about whether there was more than one person (Lawrence) in that room. The first deputy on the scene, Joseph Quinn, claimed that the 55-year-old white John Lawrence was anally penetrating 31-year-old black Tyron Garner and continued to do so after being ordered by the officer with his gun aimed at Lawrence to stop.The second deputy claimed that Garner was fellating Lawrence. The other two said they did not see sex occurring. Garner stated that he was in the kitchen by the bedroom door, shirtless and shoeless, but wearing pants. Lawrence stated that he was drunk in bed and alone.

March 16, 2002

It seems to Carpenter and to anyone reviewing the evidence (something which played literally no part in the legal case!) exceedingly unlikely that even a drunken man would continue to penetrate someone while clearly audible entry into the apartment, confrontation with the man in the kitchen, turning on the lights in the bedroom, and at gunpoint ordering him to stop. Lawrence maintained that he never had sex with Garner. (In contrast with the tumultuous sexual relationship of Eubanks and Garner…).

After more than 24 hours in jail, Lawrence and Garner pled not guilty. To have “standing” to challenge the 1973 Texas “Homosexual Conduct” statute, lawyers needed someone convicted under it. Though used to denying any rights to lesbians and gay men in the state of Texas, practically no one was ever charged under Texas’ same-sex-only sodomy law. Trying to enter the case in the computerized court docket, the charge was not listed among codes.

The arresting officer was extremely prone to making arrests instead of delivering admonitions as others would. After lawyers got the defendants to change their plea from not guilty to no contest, the justice of the peace set a fine, $100 a piece, that was too low to be appealed. The Harris County prosecutor did not object when the defense lawyer requested imposition of a higher fine (which in itself may be a unique event!). The state appeals judges (all Republicans in a state in which judges run with party affiliations) overturned the conviction 2–1.

The Christianists who increasingly dominated the Texas Republican Party, and had earlier insisted on the Homosexual Conduct law when not only heterosexual oral and anal sex but adultery and bestiality were legalized, insisted on the case being heard by the whole judicial panel and vociferously called for the removal from office of the two judges—who were the only two of the nine from the full panel who held the law unconstitutional.

The Texas state supreme court then ducked the court. After review was accepted by the U.S. Supreme Court, the state’s attorney general (now U.S. Senator John Cornyn), who was running for the U.S. Senate chose not to defend the law, so that the Harris County District Attorney. Charles Rosenthal, who had no prior experience of presenting cases to the U.S. Supreme Court, was the defender of legislating morality (with the assistance of Justice Scalia from the bench).

The facts of the case continued to be unconsidered, Lawrence and Garner enjoined by their various attorneys (coordinated by Lambda Legal) from speaking to the press. Though Lawrence and Garner were not in a relationship and very well may never have violated the Texas Homosexual Conduct Law together, the right to sexual intimacy was largely couched in a script of relationships, even while the appellate lawyers[4]to call them the “lawyers for Lawrence and Garner,” as Carpenter repeatedly does, is technically correct but pretty misleading, as Carpenter’s narrative makes quite clear were insisting that the court could reverse Michael J. Bowers[5]Attorney General of Georgia v. Michael Hardwick, et al. 478 U.S. 186 (1986) without overturning bans on same-sex marriage.

In his fiery dissenting opinion, Justice Scalia wrote:

If moral disapprobation of homosexual conduct is “no legitimate state interest” for purposes of proscribing that conduct…what justification could there possibly be for denying the benefits of marriage to homosexual couples exercising “the liberty protected by the Constitution”? Surely not the encouragement of procreation, since the sterile and the elderly are allowed to marry.

I think he was right in this (rare!) instance. Carpenter does not go so far as to commend this inference, but seems to lean that way.

Scalia also invoked ye old slippery slope: What next, bestiality? He seems to have been unaware that Texas had decriminalized bestiality… The appellate lawyers and Carpenter make clear that far from “unchanging truths,” as claimed in the plank of the 2000 Texas GOP platform insisting on criminalization of sodomy, the law they were challenging dated only from 1973.

Carpenter mentions—though it does not seem to have come up in the appeals proceedings—that the Republic of Texas did not have any sodomy law. Neither did the previous county of which Texas was a component (part of a state), Mexico, nor the one before that, New Spain. Having been a country and a part of three other countries, Texas has an interesting constitutional history that seems to have been ignored by Texas and U.S. federal courts in judging the constitutionality of the Texas Homosexual Conduct Law.

Carpenter makes the legal issues, from those of police discretion and police misconduct up to the Equal Protection and Due Process requirements of the U.S. Constitution. Since much of the challenge was to singling out homosexuals where heterosexual oral and anal sex were legal (in Texas, Oklahoma, Missouri, and Kansas), the one thing that I think Carpenter does not make clear is why the decision applied also to states where de facto enforcement of sodomy laws targeted homosexual males, but where sodomy was also de jure illegal for married heterosexuals (Alabama, Florida, Idaho, Louisiana, Mississippi, both Carolinas, Utah and Virginia).

I think that the ruling that “the Texas statute furthers no legitimate state interest which can justify its intrusion into the personal and private life of the individual” applies (straightforwardly!) to heterosexual oral and anal sex and that if Justice Sandra O’Connor’s concurrence in ruling the Homosexual Conduct Law unconstitutional had been the majority opinion, it would only have applied to the four states in which oral and anal sex between persons of the same sex was made illegal.

Having been in the Bowers majority (arguably she was the Bowers majority, though the vacillating justice who later stated he voted wrong was Lewis Powell, who infamously told his closeted gay law clerk he had never met a homosexual), O’Connor did not accept the Due Process rationale of the majority opinion, but only the Equal Protection part. (On the other hand, as Scalia scolded in his dissent, O’Connor’s position that a rational basis had to be shown for legal second-class status for a minority doomed the ban on same-sex marriage.)

Carpenter writes illuminatlingly about the individuals (starting with Eubanks, Garner, and Lawrence), about police culture (Harris County style), Texas political culture (very much including partisan election of judges), the culture (protocols) of the U.S. Supreme Court, and the changes wrought partly by increased visibility (coming out) of lesbians and gay men in the erosion of support for criminalizing same-sex sex (support that was down around 20% when the Supreme Court ruled on Lawrence v Texas). He chose an important story with many ironies and told it engagingly and informatively.

©2012, 2016 by Stephen O. Murray

Originally posted on epinions 5 April 2012

See also: Dale Carpenter’s 2002 talk at the Cato Institute on YouTube

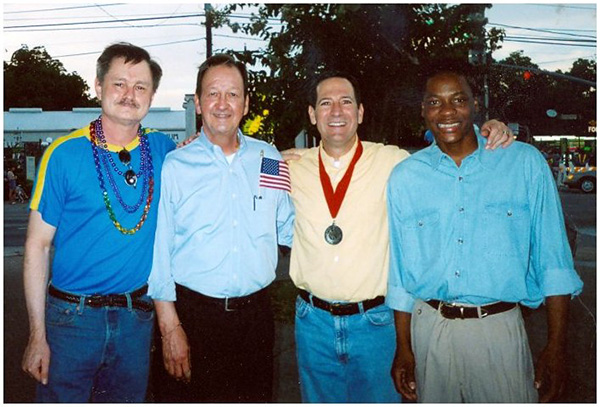

JD Doyle: “Supreme Court Ruling, June 26, 2003: Lawrence v Texas, overturning the sodomy laws nationwide,” at houstonlgbthistory.org