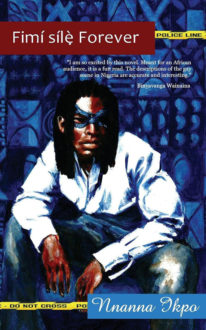

Fimí sílẹ̀ Forever: Heaven Gave It To Me

Fimí sílẹ̀ Forever: Heaven Gave It To Me

by Nnanna Ikpo

Published by Team Angelica Publishing

Published April 20, 2017

Fiction (Nigeria)

ISBN: 9780995516205

304 pgs. • Find on WorldCat

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

July 13, 2018

The draconian 2014 Nigerian Same Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act becomes law during the course of Nnanna Ikpo’s (2017) novel, Fimí sílẹ̀ Forever: Heaven Gave It To Me. The law went far beyond prohibiting same-sex marriage:

4. (1) The Registration of gay clubs, societies and organisations, their sustenance, processions and meetings is prohibited.

(2) The public show of same sex amorous relationship directly or indirectly is prohibited.

5. (1) A person who enters into a same sex marriage contract or civil union commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a term of 14 years imprisonment.

(2) A person who registers, operates or participates in gay clubs, societies and organization, or directly or indirectly makes public show of same sex amorous relationship in Nigeria commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a term of 10 years imprisonment.

Olawale (Wale for short), the narrator of the novel, is a human rights lawyer whose sexual experience is exclusively with other males, though he has convinced himself that he can be a faithful husband to Tega, a woman who works with him in a Nigerian human rights organization that mostly advocates for those engaging in homosexuality. Along with a background in which the love of his life was a male schoolmate who felt he had to marry a woman and cease homosexual activity, Wale is from a Pentecostal Christian background. He tells himself that he is bisexual, while presenting himself as a straight champion for gay rights (without ever actually saying he is “straight”).

Wale has an identical twin, Oluwole (Wole), whose emotional history, sexual experience, and inclinations are even more exclusively homosexual than Wale’s. Wole is also engaged to be married to a woman, Lola, who works for the same human rights organization.

The twins were unaware of each other until they were eleven but then went to the same schools and worked in tandem. They famously won a case for a battered effeminate student (Tanni Cross) against a boarding school that failed to protect him.

I have to say that even before the 2014 law, I find this legal victory difficult to believe in (too good to be true). I also find it very difficult to believe that neither of the fiancées ever considered the possibility that their affianced might have had sexual experience with other males and are totally surprised and appalled when evidence of that is thrust upon them (by the wife of Wale’s great adolescent love, who has not been able to stay on the straight and narrow heterosexual path).

The violence against those perceived to be homosexual is all too believable, and the twins flee to South Africa (the author was at the University of Pretoria when the author note was written, and his blog — http://nnannaikpo.blogspot.com/ —suggests he still is there).

What seems to me to be an insightful analysis applicable far beyond Lagos is made by Wale:

The crime that attracts homophobia is not homosexuality, but vulnerability: it is poverty, effeminacy, outspokenness. In the face of dangerously hot, homophobic Nigeria, only the protected, wealthy, ruthlessly self-serving and politically connected could ride, win, laugh, and lead normal, if not ideal lives — as people of means have done in the past, do today, and will continue to do in the future — for homophobia is innately cowardly. (p. 197)

The ready embrace of duplicity about same-sex desire on the part of publicly heterosexual men is well articulated earlier (by Iska): “That we have each other matters to me. Secrecy makes it safe and all the more desirable. Let’s not be like those who don’t understand that we, as African men, have our place of honour which must be protected and respected in spite of what (or who) we are doing” (p. 31). This widespread management of discrediting information has a lot to do with why some Africans deny that homosexuality exists in sub-Saharan Africa in general, or, specifically among the Christian Yoruba.

The front cover blurb from Binyavanga Wainaina affirms that “the descriptions of the gay scene in Nigeria are accurate.” The scene described was secretive even before the 2014 law, with everyone except the blatantly effeminate (shelleh) passing as straight, and the blatantly effeminate at a constant risk of physical violence. (A more decorous label for the more respectable, secret practitioners is “ti bii”—“of that kind.”)

For me, the novel drags in the middle section in which Wale is a human rights law professor at his (and Wole’s) alma mater, Kola [Daisi] University, where the too-good-to-be true president provides unwavering support to Wale and his project of a symposium coinciding with graduation focused on abuse of homosexuals. The melodrama, not least the conception (I mean physical conception) of the twins is quite thick. And sympathetic as I am to women whose handsome husbands (or, in this case, fiancés) are not candid about their same-sex desires and histories, I find the naiveté of Tega and Lola very difficult to credit. Also the flashbacks are often awkward and confusing, the prose sometimes “dicty” (to borrow an old African American label), and the sexuality very phallic.

For an animated deconstruction of the 2014 law (running 39 minutes) see https://nostringsng.com/nigeria-animation-video-nigeria-gay/.

There is also a 5-minute interview of Ikpo at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2fcUdq74-rA&feature=player_embedded in which he says he is Igbo.

© 2018 by Stephen O. Murray