Father and Son

Father and Son

(Otets i syn)

Directed by Aleksandr Sokurov

Written by Sergei Potepalov

Premiered May 25, 2003, at Cannes Film Festival

Drama (foreign: Russia)

83 min. • Russian with English subtitles

Review by Stephen O. Murray

September 5. 2012.

Alexander Nikolayevich Sokurov (1951–) is the most acclaimed living Russian filmmaker. He won the Golden Lion (best film) at the 2011 Venice Film Festival for his tedious adaptation of Faust and is best known for the single-shot feature tracking through the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg with a succession of historical tableux, Russian Ark (2002).

I thought his movie about Japanese Emperor Hirohito at the end of WWII, The Sun (2004), was more interesting than Russian Ark, and I actually liked the 2007 Alexandra in which a mother played by Galina Vishnevskaya (a former opera star and the widow of Mitslav Rostropovich) visits a Russian military camp during the Second Chechen War (her son is an officer usually out on patrol and she wanders around the base and into the neighboring town on her own).

I watched Father and Son before and found it opaque, even for a Sokurov film (in the Tarkovsky tradition: Sokurov made a tribute documentary about Tarkovsky, Moscow Elegy (1988)). I rewatched Father and Son partly to try to see if I missed something of significance. The running time is only 82 minutes, with credits occupying the last four. The version that premiered in Cannes is listed as running 83 minutes and the Russian version 97. I definitely wonder what is in those additional 15 minutes, but…

I said I rewatched in partly to see if I missed something the first time through, but my primary purpose was to try to see if it could be viewed as not homoerotic. At Cannes, Sokurov went off into a tirade at decadent westerners’ dirty minds (“low meaning”) exhorting viewers “to be very attentive; don’t try to put your own complexes onto the movie.”

Though I think the author (writer-director) can speak of his or her intent, I don’t think that he or she has the final word on the product. Sokurov’s movie begins with a pair of seemingly nude men grappling in bed. They are wearing military-issue underwear, but it is several minutes before that is glimpsed. That is, only naked torsos appear. It turns out that the son [Alexei Nejmyshev] has been having a(nother) nightmare and his father [Andrej Shetinin], with whom he shares a rooftop apartment, has been waking and reassuring him.

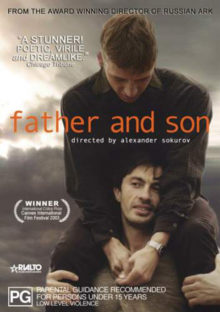

With some effort, I can discount any erotic intent of the father and son in this scene, but what of how Sokurov shot it? Later in the movie there is a very extended scene of the two gazing intently into each other’s eyes across a very short distance. The scene ends with the younger resting his head on the chest of the older one while the older one strokes the hair of the younger one. I find it difficult to believe that this degree of physical intimacy is devoid of any erotic component and wonder if Sokurov fails to understand the difference between “erotic” and “sexual.” I do not infer that the 20-year-old and 40-year-old who have chosen to live together are having genital contact, but I wonder how many 20-year-old Russian males ride around on their father’s shoulders (see the DVD cover photo).

There is a 20-year-old female [Marina Zasukhina] whom the father seemingly has appropriated from his son. Through a window, the son plaintively asks her why he can’t love both her and his father. She does not answer but clearly has written off any possible relationship with him.

That is the context for the first intoning of the formula “A father’s love crucifies the son; a son’s love for his father lets himself be crucified.” The implication (not to mention trying to avoid inferring “low meanings”!) is that more is involved in this formulaic expression than yielding up his blond girlfriend to his father. I doubt that Russian Orthodox theology differs from the evangelical Protestantism in which I was catechized once upon a time that “God [the Father] so loved the world [humankind] that he gave his only begotten son that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life” (John 3:16). That is, Jesus “suffered under Pontius Pilate; was crucified, dead and buried” not to please his heavenly father but to make salvation possible for human believers. Christ on the cross does not forgive his father, but exhorts: “Father forgive them, for they know not what they do” (Luke 23:34).

The Russian soldier son is supported by his father and has no occasion to cry out asking about being abandoned (cf. Matthew 27:46).

It seems to me that Sokurov’s fury about reading “homoeroticism” is pre-Freudian, unaware of erotic underpinnings (distinct from sexual actions). The son, Alexei, seems to me to have more in common with Oedipus than with the crucified Christ. I am not convinced that the Oedipus complex is universal (Melford Spiro to the contrary notwithstanding), but even without any mother either present or having been around in the recent past, the son in the movie still is the rival for the affection (and more) of a woman. Alexei knows who his father is and has chosen to follow him into the army and to live with him rather than unknowingly slaying his father, as Oedipus did Laius. At least some ambivalence to and resentment of his father is evident in the movie… which offers nothing so dramatic as slaying anyone or sexual congress with anyone.

I don’t know what Sokurov may have supplied actor Andrej Shetinin in explanation for motivation for his part or what the actor was thinking/feeling while gazing at or playing with or comforting his son. The son points out that he is the age now that his father was when he was born. The father says nothing about this, but he must see something of his younger self in the son who has followed him into the army (albeit that of the Russian Federation rather than of the Soviet Union, not that this change is even alluded to within the movie).

I don’t know what Sokurov may have supplied actor Andrej Shetinin in explanation for motivation for his part or what the actor was thinking/feeling while gazing at or playing with or comforting his son. The son points out that he is the age now that his father was when he was born. The father says nothing about this, but he must see something of his younger self in the son who has followed him into the army (albeit that of the Russian Federation rather than of the Soviet Union, not that this change is even alluded to within the movie).

In addition to a wrestling training scene in which his father observes him, Alexei has scenes with two lads of his own age. I don’t see anything erotic in the baiting of and then friendliness to a boy [Aleksandr Razbash] whose father was a soldier who has gone missing (someone the father knew). The two young men leave the confines of the apartment building and the sickly greenish light there and in the military base scenes (for a golden light).

I think the movie is set in St. Petersburg, though it was shot in Lisbon, and the young men go up to the alcazar.

But then there is a neighbor of the generation, if not exactly the same age, as Alexei. Fyodor [Fyodor Lavrov] looks to me to be in love with Alexei and wants to move in with Alexei and his father. I’d enjoy Sokurov attempting to explain that there is nothing homoerotic in how Fyodor looks longingly at the two soldiers! Not that it is reciprocated: Alexei tells Fyodor to be content with being neighbors and clearly wants to maintain the isolation à deux with his father, a man he is trying to be (which to me is very homoerotic—and distinct from wanting to have; and from longing for approval of fathers).

In looking for a nonerotic interpretation of the movie, I have revealed everything about the plot, or, perhaps more correctly, that there isn’t one. I’ve also mentioned how ugly the lighting and sets are (in contrast to the 19th-century Romantic painting influences of shots in Sokurov’s earlier [1997] Mother and Son”. Alexei plays with a soccer ball some, both inside the apartment and out on the roof, with or without his father’s participation.

The DVD has only a photo gallery and trailers for the movie and for The Russian Ark in the way of bonus features.

(BTW, Sokurov’s father was an army officer, and Sokurov’s childhood involved moving from army base to army base, so the situation of soldiers is familiar territory for him.)

First published on epinions, 5 September 2012

©2012, 2017 Stephen O. Murray