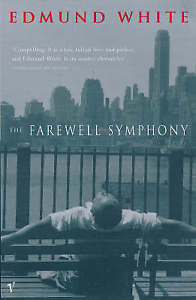

The Farewell Symphony

The Farewell Symphony

by Edmund White

Published by Chatto & Windus

First published in London, May 1, 1997

Vintage ed. published September 1, 1998

Fiction (autofiction)

504 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

December 29, 1997.

It took me months, but I finally finished Edmund White’s The Farewell Symphony (which prompted me to listen to “Ich bin der Welt abhadned gekommen” (“I have lost track of the world”), the Rückertlieder to which the narrator listened over and over in Paris, as more and more of his friends and acquaintances died in New York.

Dame Janet Baker produces the beautiful, plaintive sounds of the Mahler of the 5th symphony’s adagietto, particularly in the final couplet:

Ich leb’ allein im meineim Himmel,

In meinem Liebem, in meinem Liebem, in meinem Lied.

(I live alone in my heaven / In my loving, in my loving, in my song.)

Of course, White is wrong that Haydn’s Farewell Symphony (#45) ends with a lone violinist. It ends with a pair, which is in this context not double, but infinitely more than one…

Author and narrator both find true (reciprocal) love after years of unreturned (if not invariably unrequited) loving along with promiscuous receptive sex.

Author and narrator both find true (reciprocal) love after years of unreturned (if not invariably unrequited) loving along with promiscuous receptive sex.

I do not think that White provides a critique of the clone lifestyle (though the analogy of the Mineshaft to Hell raises some doubt, and also wondering if the gloryholes there were anonymous, as those of today’s gay clubs are not).

Like the (surely autobiographical) narrator of Andrew Holleran’s The Beauty of Men, White’s is acutely aware of the exclusion of the aging from youth culture. “We held off aging [and growing up?], but cannot indefinitely,” they painfully realize.

At “the end of the gay fast lane” for White was love. Loneliness followed love, not promiscuity.[1]Contra Bruce Bawer’s reading of “the point” of the two books by Violet Quill survivors. I don’t remember States of Desire “mocking couples” either, though in FW White recalls the … Continue reading

The assignment of pseudonyms to figures who are obvious even to me (e.g., Virgil Thompson and James Merrill) and not to Foucault is puzzling.

I hope that “Eddie” is a fictional character, not an accurate portrait of Merrill. I admired Merrill’s memoir and don’t want to revise my view of him as heedless and even stupid, which is how White portrays him. (Indeed, White’s portrayals of creative writers here—and in the later City Boy, in 2009—are generally vicious). I suspect that “Max” is an un-fictionalized Christopher Cox, though…

I know I’m missing various clefs, and I find much of the sex abject and the whole somewhat lumpy, though the inability to write about life with Brice provides a credible and affecting structure and ties the clone-era memoir and the memoir of AIDS losses together. Given the attacks on the book as it is, I can imagine the furor there would have been had White separated what he saw as two books.

I accept that what he wrote is more or less the way it was, and readers have projected their own views of “promiscuity” onto the screen of (merciless) reportage White produced.

29 December 1997

©1997, 2016, Stephen O. Murray

Image from “Edmund White Comes Out Swinging,”

an interview by Thomas Rogers published by SALON on Oct. 15, 2009.