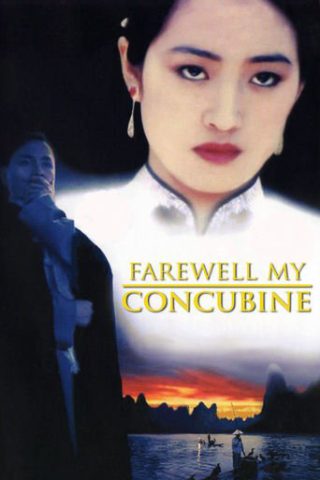

Farewell, My Concubine (Ba wang bie ji)

Farewell, My Concubine (Ba wang bie ji)

Directed by Kaige Chen

Written by Pik Wah Lee

Released October 15, 1993

Drama (romance)

171 min.

Review by Stephen O. Murray

January 21, 2001.

Chen Kaige’s controversial (banned in China) 1993 film, Ba wang bie ji (Farewell, My Concubine) starts in 1925 and ends in 1977. It is not subtle, but is compelling.

None of the main characters behaves well, but the blows of history are so relentless that it is hard to condemn any but the youngest of them, the adopted student who becomes a Red Guard. The other characters are at times unreasonably hard on each other, but it is easy to make excuses for each one of them. How much heroism can be expected of anyone? Each of them manages heroism at some times (more than one could say of Pu Yi, the last emperor, focus of Bertolucci’s film set across approximately the same swath of Chinese history with disaster following disaster following disaster). The courage of each fails on other occasions. But no one should have to go through what they (and all of China) did.

As in the more overtly gay films from Japan (Okogé, Hush!) and Taiwan (Wedding Banquet, Crystal Boys), the men involved with each other create a quasi-family (after Juxian miscarries Xialou’s child), here with a wife and a foundling (played as a young adult by Han Lei) who far outdoes Eve Harrington’s perfidy (in All About Eve) during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. Was the cultural revolution “karmic retribution” on them? I think not, for that crime could possibly deserve such a punishment of a vast populace?

As in the more overtly gay films from Japan (Okogé, Hush!) and Taiwan (Wedding Banquet, Crystal Boys), the men involved with each other create a quasi-family (after Juxian miscarries Xialou’s child), here with a wife and a foundling (played as a young adult by Han Lei) who far outdoes Eve Harrington’s perfidy (in All About Eve) during the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. Was the cultural revolution “karmic retribution” on them? I think not, for that crime could possibly deserve such a punishment of a vast populace?

The pair are referred to as “stage brothers” (at least in the subtitles). Dieyi address Xialou as “older brother” (though this is not carried in the subtitles), whereas Xialou always refers to Dieyi by name.

Xialou (Zhang Fengyi, who went on to play the assassin in Chen’s The Emperor and the Assasin) wants Dieyi (Leslie Cheung) to be best man at his wedding. Dieyi may have been convinced himself (having been beaten into his role as the concubine in the Peking Opera love tragedy) that he is a woman, but clearly not a sister (nor a wife). He plays the consort who truly loves the emperor and whom the emperor really loves (the character Xialou portrays in the opera Farewell, My Concubine presumably had one or more female wives, too, but love was expected from concubines rather than from wives in arranged marriages, particularly those arranged with dynastic considerations paramount).

Hong Kong superstar Leslie Cheung (A Chinese Ghost Story, Days of Being Wild, The Phantom Lover, Happy Together) was very beautiful in or out of drag, with long or with short hair. Cheung’s Hie Dieyi is wholly believable as a Peking Opera star and as a sexually confused and frustrated man wrapped up in his stage role. Perhaps since it did not come naturally (“I am by nature a boy” he keeps saying instead of “I am by nature a girl” as an apprentice), he is enveloped in it offstage as on (role engulfment of a tentative self). Xialou’s art is far less of an accomplishment, being considerably more in accord with his swaggering temperament. Still, he is no match for the steel wills of either his male “concubine” or his ex-prostitute wife Juxian (played by Gong Li, who had been the muse of Zhang Yimou from Red Sorghum through Raise the Red Lantern, until the broke up after making Shanghai Triad; she went on to star in Chen’s Temptress Moon and (again with Zhang Fengyi) The Emperor and the Assassin). Nor is Xialou ready for what history has in store for them (and the Chinese people in general, but particularly for “decadents” portraying feudal relations in popular entertainments).

Hong Kong superstar Leslie Cheung (A Chinese Ghost Story, Days of Being Wild, The Phantom Lover, Happy Together) was very beautiful in or out of drag, with long or with short hair. Cheung’s Hie Dieyi is wholly believable as a Peking Opera star and as a sexually confused and frustrated man wrapped up in his stage role. Perhaps since it did not come naturally (“I am by nature a boy” he keeps saying instead of “I am by nature a girl” as an apprentice), he is enveloped in it offstage as on (role engulfment of a tentative self). Xialou’s art is far less of an accomplishment, being considerably more in accord with his swaggering temperament. Still, he is no match for the steel wills of either his male “concubine” or his ex-prostitute wife Juxian (played by Gong Li, who had been the muse of Zhang Yimou from Red Sorghum through Raise the Red Lantern, until the broke up after making Shanghai Triad; she went on to star in Chen’s Temptress Moon and (again with Zhang Fengyi) The Emperor and the Assassin). Nor is Xialou ready for what history has in store for them (and the Chinese people in general, but particularly for “decadents” portraying feudal relations in popular entertainments).

Each era (warlord, Japanese, Kuomintang, communist) seems worse than its horrible predecessor, and the Cultural Revolution outdoes even the suppressions of initial life in Mao’s ideology-deranged society. Dieyi finally acts out her suicide for real on the verge of the post-Cultural Revolution order which restored opera. As in the 1960s Hollywood movies, the homosexual characters must die. It seems that Dieyi’s patron is killed and Dieyi merges with his role forever with a real suicide. (This is reminiscent of Ronald Colman’s actor turning into Othello and really killing the actress playing Desdemona in A Double Life).

As in Chen Kaige’s To Live about less glamorous Chinese buffeted by war, revolution, and the fatal idiocy of those who rose to decision-making responsibilities during the Cultural Revolution, the cinematography is superb. So are the performances. The horrors of every regime that ruled China during the 20th century are very clear in both films.

The DVD, alas, lacks any bonus features. A primer on the history, on Peking Opera, and traditional Chinese expectations of relationships with wives and with concubines would be useful to many chronocentric, ethnocentric historical-knowledge-lacking Americans.

The transfer is clean but not anamorphic. But it sure has grand set and costume design and art direction, plus compelling performances, especially Cheung’s tortured one, which is made even more poignant by the actor’s later suicide. Ma Mingwei was also outstanding as the child being beaten into the role (seemingly his only screen role).

Farewell, My Concubine (co-)won the Palme d’or at the Cannes Film Festival. Its cinematography, by Cinematography by Gu Changwei, received an Oscar nomination, and it was nominated for Best Foreign Language Film having won a Golden Globe, the BAFTA, and awards from the societies of film critics in New York, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, and other places. (Yes, yet another in the long and ignominious list of Oscar mistakes, with the statuette going to the undeserving and forgotten Spanish light romantic comedy Belle Epoque.)

published by epinions 21 January 2001

2001, 2016, Stephen O. Murray