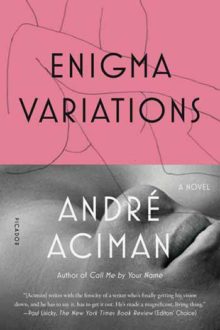

Enigma Variations

Enigma Variations

by André Aciman

Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux

Published January 2, 2017

Fiction

288 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com • WorldCat

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

November 24, 2017

Being a major admirer of Out of Egypt and Call Me By Your Name, I was somewhat disappointed by André Aciman’s Enigma Variations.

I refuse to accept that it is a “novel.” Its five stories (/novellas) are each about erotic obsessions of the same character, Paul[o], across some time. There is variation in age and sex of those about whom Paul obsesses but no satisfaction, even when the loves are requited.

The first, longest, and (IMHO) best “variation,” “First Love,” has him at twelve on Sicily or some smaller island off Sicily longing for the touch (and attention) of a young, virile cabinetmaker, Giovanni (shortened to Nanni). Paul drops by more and more frequently to help refinish a small desk and two frames his parents have hired Giovanni to refinish. The ardent fantasizing of a twelve-year-old for someone twice his age will make many uncomfortable in this day of pedophile panic. For me, what Paul learns when he returns to the burned-out house where he summered as a child and pubescent boy is more interesting than the earlier yearning and includes discovery of sinister goings-on before and after the house was burned. (BTW, Paul and his father discuss Beethoven’s Diabelli variations; there is no mention of Elgar in the book.)

The following story, “Spring Fever,” suggests that the homoeroticism of the twelve-year-old was outgrown. The adult Paul lives in New York City with Maud. He spots her talking animatedly to another man in a restaurant and assumes they are having an affair. He counsels himself in discretion so as not to reveal he has seen the tryst. At and after a party, he learns that Maud is aware of his attraction to men—and he is wrong about his surmises regarding Maud.

Then it is back to full-throttle obsession with another male body, that of Manfred, a hung German-born teacher and ace tennis player whom Paul sees (naked) every week day. His fantasies of coupling with Manfred are more explicit than those he’d had about Giovanni, whom he never saw naked. As usual (the invariant?) he is wrong about the feelings of his “beloved,” that is, the one about whom he is agonizing/fantasizing.

There is nothing about the process of recoupling. The following story, “Star Loves,” involves Chloe, a woman with whom Paul did not have sex as an undergraduate, though both of them were very attracted to each other and frequently thought about it. The reconnect for some abbreviated fling happens in later years. Paul confesses that he was off having sex with other young men in the library stacks, and Chloe tells him everyone knew he liked men. Another brief sexual liaison following long acquaintanceship, and in which Paul was the desired rather than the desiring one, is woven into the narrative. In that the physical congress does not occur until Paul is no longer than man’s student, this will be less unsettling than the attempted adult molestation in “First Love.”

The last and least (not just in length), “Abingdon Square” (first published in Granta), involves more agonizing about whether another wants Paul physically. There is no real fire either from the aging editor and the opportunistic freelancer named Heidi. Manfred offers advice by e-mail from Germany on how to seduce her or at least to clarify her intentions. Again, there is nothing about how Paul uncoupled. I guess it is possible that he didn’t and that he and Manfred have an open relationship, and their separation by the Atlantic Ocean is temporary.

Paul does not seem to have a sexual identity (unlike Manfred). (Note the pink of the cover, above lips that are not obviously male or female, though photographed by the gay Herbert List). He is not really closeted. The intensity of his homoerotic desires is stronger and more explicit than his heterosexual desires, which though they exist are blocked by diffidence (though taking two years to come on to Manfred counts as pretty damned diffident, and he never told Giovanni what he wanted, though that was not lost on Giovanni).

I thought the book ended with a whimper. There is some beautiful writing, and some that may more than verge on “purple” prose. Yearning, Aciman (who was born two days into 1951 in Alexandria) definitely can do (even better, I think, in Call Me By Your Name, which won a 2007 Lambda Literary Award).

©2017, Stephen O. Murray