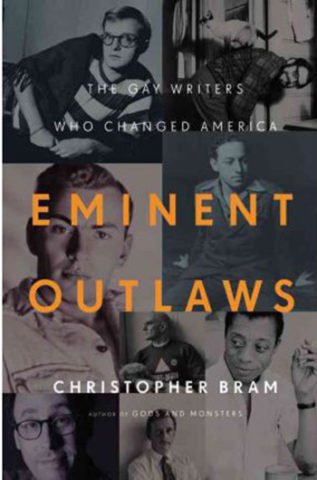

Eminent Outlaws: The Writers Who Changed America

Eminent Outlaws: The Writers Who Changed America

by Christopher Bram

Published by Twelve

Published February 2, 2012

History / Literary Criticism

372 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

March 13, 2012

The thesis announced in the subtitle of Christopher Bram’s new overview of American gay literary history after the Second World War, Eminent Outlaws: The Gay Writers Who Changed America, I consider not just dubious but bordering on silly.

I prefer to consider the “thesis” as a pretext to write about a number of writers and writings that interest Bram. Although I have read all the novels and memoirs Bram discusses in any detail and a lot of the biographical sources on which he drew, I still found the chronological view of a number of these writers illuminating, and the reception of work by these prominent (I don’t know about eminent!) gay writers from New York cultural gatekeepers (particularly reviewers for the New York Times) that Bram excavates outright appalling.

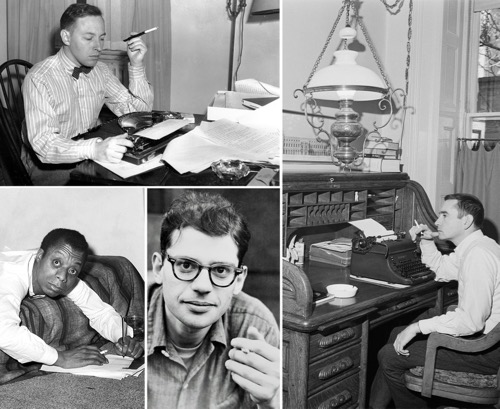

Bram begins in 1948 with the publication of Gore Vidal’s The City and the Pillar and Truman Capote’s Other Voices, Other Rooms. The gay content of the latter was exaggerated in swipes from critics, whereas Vidal’s novel delved into the “unspeakable.” There is a gay character in Capote’s first novel, and adolescent same-sex sex in Vidal’s second. An attempt to rekindle a relationship (love?) is spurred, which leads to violence (what violence was altered between editions of The City and the Pillar). The relationships in both those novels and in James Baldwin’s whiteface same-sex love tragedy, Giovanni’s Room (1956), involve protagonists without any gay/homosexual identity (despite strong autobiographical elements from each of the authors), and the idealized love of isolation à deux is threatened by the stigma of “queer” in The City and the Pillar and to the white-face failure at love to whom Baldwin gave his brother’s name, David. There are no gay networks or proto-community in Vidal’s or Capote’s books, and the Paris homosexual subculture is a source of threat rather than any solidarity or support to the love in Giovanni’s room. (Hell is other men attracted to Giovanni in David’s view.)

Giovanni’s Room is also an archetype of the period requirement “The Homosexual Must Die” if he is allowed onto the page (or screen). The tearing to pieces and cannibalism in Tennessee Williams’s 1958 play Suddenly Last Summer is extreme, and Sebastian Venable does not even appear onstage (his grisly end is recalled by his cousin, whom Sebastian’s mother seeks to have lobotomized). Though Bram does not mention it, this requirement did not govern the two 1948 books: the delicate 13-year-old Joel (clearly an autobiographical portrait) does not die, nor does his transvestite uncle Randolph. And it is the heterosexual former sexmate, Bob, who is killed in the first version of The City and the Pillar (the homosexual character is, thus, a homicidal menace; and Uncle Randolph shoots, albeit accidentally, Joel’s father in Other Voices, Other Rooms). And insofar as Tom in The Glass Menagerie is gay (which makes sense, though there is no overt reference to this), he is remarkable in that he gets out (of the play and away from St. Louis) alive. Even the aging English instructor of Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man does not survive, though not a suicide or homicide victim. (However, gay characters survive in his earlier written-in-America novels, The World in the Evening, and Down There on a Visit, and the not specifically identified-as-gay narrator of his 1945 Prater Violet, who ends the short novel asking “Why don’t you kill yourself?”).

Having mentioned all the leading figures of the first half of Bram’s book except for Allen Ginsberg, I will track back to his claim:

The gay revolution began as a literary revolution. Suddenly, after the war, a handful of homosexual writers boldly used their personal experiences in their work. Their writing was the catalyst for a social shift as deep and unexpected as what was achieved by the civil rights and women’s movements.

“Catalyst” is a pretty shifty claim. The idea that I think matters is that things don’t have to be the way they are. A conception of social change is strikingly missing even from Howl! A possible idyll of two men loving each other apart from the world in The City and the Pillar and Giovanni’s Room harkened back to Edward Carpenter (whose relationship with a working-class lad was the model for E. M. Forster’s Maurice, written in 1913–14 but not published until 1971, after Forster’s death, supervised by Christopher Isherwood). And the portrayal of a fear of other homosexuals preying on the beloved male of a version of the male author’s was a central theme in André Gide’s only novel, Les faux-monnayeurs (published in French in 1925 and translated as The Counterfeiters in 1927).

There is dismay at the way things are in regard to same-sex love in the works of the late-1940s and 1950s already mentioned, but even in the writing of the most political of these writers, Gore Vidal, a fantasy of living together in a world without labels is the maximum aspiration, the same impossible dream of David for Giovanni in Baldwin’s.

Not only did these literary works not change the world or conceptions of those labeled deviates, the “pioneers” retreated, but Vidal, Capote, Williams, Ginsberg, or Isherwood did not trod the path toward gay liberation (or even homophile rights or representation of gay characters) during the 1950s (or beyond in the cases of Capote, Williams, and, at least arguably, Baldwin). Homosexuality remained offstage in Williams’ plays and the fiction by Capote (for the rest of his life) and Vidal (until the savage satire on patriarchy by the transsexual Myra Breckinridge; and Vidal insisted that homosexual was an adjective, not a noun, that homosexuals do not exist).

Bram mentions a third book that was published in 1948, one that I think did vastly more to change conceptions about what was, in particular the rarity of homosexual experience among white American men: the “Kinsey Report” (Alfred Kinsey, et al., Sexual Behavior in the Human Male). Moreover, reactions to the first Kinsey report made homosexuality a topic of open discussion even in respectable mass-circulation media. Revealing to individuals that they were not one of a kind was (and is) a vital step to group consciousness, which is a prerequisite to group action: a conceivable group precedes conceivable change of stigmatization of a category of persons. Despite focusing on behavior and largely ignoring identity, Kinsey’s data did this; Capote, Vidal, Baldwin, and Williams did not (and though somewhat more equivocal, I would say that the 1950s writings of Ginsberg and Isherwood did not either).

Bram mentions a third book that was published in 1948, one that I think did vastly more to change conceptions about what was, in particular the rarity of homosexual experience among white American men: the “Kinsey Report” (Alfred Kinsey, et al., Sexual Behavior in the Human Male). Moreover, reactions to the first Kinsey report made homosexuality a topic of open discussion even in respectable mass-circulation media. Revealing to individuals that they were not one of a kind was (and is) a vital step to group consciousness, which is a prerequisite to group action: a conceivable group precedes conceivable change of stigmatization of a category of persons. Despite focusing on behavior and largely ignoring identity, Kinsey’s data did this; Capote, Vidal, Baldwin, and Williams did not (and though somewhat more equivocal, I would say that the 1950s writings of Ginsberg and Isherwood did not either).

The homophile (Mattachine Society, ONE, Daughters of Bilitis) vision of even gradualist change pushed by minority organizations would seem to me to have come from reformist organizations such as the B’nai B’rith Anti-Defamation League, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and the Urban League. Their gradual successes are more plausible factors in conceiving change as possible. The black and student movements were important not just as examples, but because many of those who would participate in the early gay liberation organizations had direct experience in them (especially between 1963 and 1966).

And far more important than a few representations in fiction of doomed (or at least failed) same-sex sexual relations, major social changes were underway at the time the American homophile movement emerged. Just prior to the 1948 publications was a major war, the effects of which included the massive mobilization of men into the single-sex environment of the armed forces and unprecedented recruitment of women into the wage-earning workforce. The former moved many men from small towns, through cities and in many cases overseas; the latter moved some women out of the house and away from expectations about what constituted “women’s work.” Both were isolated from the opposite sex to extents unusual for adults, and freed from many constraints on same-sex bonding that previously had been taken-for-granted.

As I suggested in American Gay (University of Chicago Press, 1996), work on reference groups by the social scientists employed to study morale may inadvertently have facilitated tolerance. A wartime task-force report commissioned by the Surgeon General, and declassified decades later recommended, “’particularly for soldiers overseas, homosexual relationships should be tolerated’ as long as they were private, consensual and didn’t disrupt the unit.” Moreover, “The tension of living in the all-male world of the military, the comradeship that came with fighting a common enemy and the loneliness of being away from home in strange cities looking for companionship all helped to create a kind of ‘gay ambiance’” (both these quotations are from Alan Bérubé’s Coming Out Under Fire). This ambiance was particularly evident in large disembarkation cities such as New York, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. The wartime influx of young and available military personnel was an impetus not only to homosexual behavior but also to the development of proto-gay bars that provided some measure of company.

Being stationed overseas helped many to realize that American sanctions against homosexual behavior were not universal and inevitable. The social disorganization and impoverishment in war-zones clearly enhanced the sexual availability of the local populaces (of both sexes). A lesser legal concern with homosexual behavior long predated World War II, both in the Pacific societies and in the European nations governed by the Code Napoléon. Even after the war, expatriates marveled at the greater freedom from legal persecution in France and Italy, as early issues of ONE as well as the works of James Horne Burns, James Baldwin, Gore Vidal, and others attest.

“The gay revolution” was a part of “the sexual revolution,” for which the discovery of antibiotics like penicillin was an important precondition. (Birth control pills were not directly important to the “gay revolution,” though the challenge to patriarchy and against discrimination on the basis of sex connected to challenges of discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation was.)

Within these United States, the long-term trend from farming and manufacturing to service occupations provided slots for men and women who were relatively detached or seeking to be autonomous from their families (this is highly intercorrelated with urbanization). The formation of a critical mass of people viewing themselves as defined to some extent by homosexual desires was the central precondition for change. The formation of a critical mass of people viewing themselves as defined to some extent by homosexual desires was the central precondition for change. I do not see how reading The City and the Pillar, Other Voices, Other Rooms, or Giovanni’s Room fostered a sense of solidarity among men who loved men (or women who loved women, invisible in these books and in Howl!).

OK, I can understand that a novelist likes to think that novels are momentous, but these novels, plays, and poems did not make a social revolution. I reject Bram’s thesis, but he tells good stories about the lives and inter-relations not only of the first post-WWII generation of American gay writers but of later ones, with particular attention given to Edward Albee (who has not written any plays with major gay characters, though the attacks on him along with Tennessee Williams and William Inge during the 1960s by Stanley Kauffmann and Philip Roth are striking), Mart Crowley (who took the admonition to write about gay characters), Tony Kushner (who wrote one play with some major gay characters), and Larry Kramer (whose importance I do not think is for his creative writing), poets James Merrill, Frank O’Hara, and Mark Doty, and to novelists Edmund White, Andrew Holleran, and Armistead Maupin. Other than the expatriated Englishmen Christopher Isherwood and Thom Gunn, Maupin is the only writer Bram considers who did not reside on the East Coast (or Europe). (There is a bit about Michael Cunningham, who was born in California but whose novels and nonfiction are set on the East Coast). Particularly noticeable to me, as someone who is two years older than Bram so had the same choice of reading Bram did when young, is John Rechy, someone else with interesting stories and whose first book, City of Night (1963) stimulated a vicious review in the then-new New York Review of Books. Bram gives Rechy only a clause in which he categorizes City of Night as “highly praised.”

(I’d be surprised if Bram did not read Gide, Genet, and Mishima, The Memoirs of Hadrian and the Satyricon when young, as I did (though perhaps not Sartre’s tome Saint Genet, as I did); Pasolini, The Conformist, Ernesto, and The Carnivorous Lamb in the mid-1970s, before the gay laments of Holleran, Kramer, and White of the late-1970s. For forming a view of representations of same-sex desire, not just foreign experiences but foreign writers, going back at least to Plato, influenced proto-gay and gay Baby Boomers like us.)

I think the book has far too much about Capote, whose contributions to gay literature are close to nil, and Larry Kramer, whose contributions to literature are close to nil. I think that Samuel Delany, Robert Duncan, Robert Glück, Richard Howard, James Purdy, Reynolds Price, and Matthew Stadler are more deserving of discussion in a history of gay literature than Capote and Kramer. (Plus I picked up resonances from the Wapshot novels of John Cheever before I knew that either he or I was gay and before he wrote the masterpiece of male-male love Falconer. And would venture the guess that the mystery novels of Joseph Hansen did more to show questioning readers the possibility of gay life than White, whose work I revere, and the other Violet Quill writers of whom I am more dubious (than I am of White and than Bram is).

Well, every moderately informed reader will have opinions about who is missing and who should not have commanded so much attention. Though giving no indication of recognizing his geographical bias, Bram attempted to forestall criticism of his selectivity: “This is not an all-inclusive, definitive literary history. I do not include everyone of value or importance. Nor am I putting together a canon of must-read writers. I am writing a large-scale cultural narrative, and I include chiefly those authors who help me tell that story-and who offer the liveliest tales.”

Yeah, well, this does not convince me, especially in regard to Delany, Duncan, and Rechy; or William S. Burroughs about whom I don’t need to read more than I have!

Eminent Outlaws is good about changes in publishing and about the importance (which I think has declined less than he does) of New York reviews. Eminent Outlaws has an almost novelistic structure, making it much closer to being a page-turner than most works of literary history. And what he says about changing contexts strikes me as sound, though failing to consider the social changes connected to the world wars, urbanization, antibiotics, and other mobilizations against discrimination.

Bram is the author of nine novels, the most famed of which is Father of Frankenstein, the basis for the movie Gods and Monsters (whose star, Ian McKellan supplied a back-cover blurb for Eminent Outlaws). See my reporting on a San Francisco stop on the book tour for the seventh, The Notorious Dr. August, here.

and my review of his collection of essays on gay literature and other matters, Mapping the Territory.

first published by epinions, 13 March 2012

©2012, 2017 Stephen O. Murray