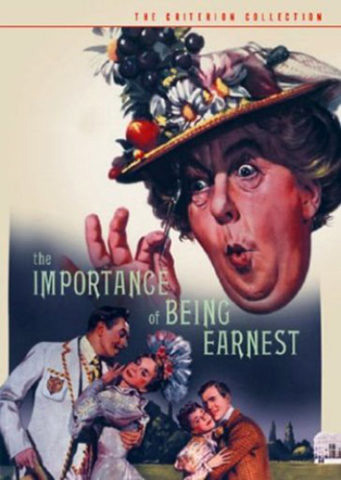

The Importance of Being Earnest

The Importance of Being Earnest

Directed by Anthony Asquith

Written by Oscar Wilde and Anthony Asquith

Released June 2, 1952 (London)

Comedy

95 min.

Directed by Oliver Parker

Written by Oscar Wilde and Oliver Parker

Released June 21, 2002 (USA)

Comedy

97 min.

Review by Stephen O. Murray

July 1, 2002.

Recently seeing the new, mangled, and tarted-up movie version of Oscar Wilde’s best play, The Importance of Being Earnest (1895), made me go back and watch the superior 1952 (in-color) version again.

Anthony Asquith trusted that Wilde’s words alone would make his film. His direction was carried by Edith Evans, a great actress who was born to play Lady Bracknell; Michael Denison, who was born to play the sly Algernon; Richard Wattis, the perfect butler; Margaret Rutherford, a hilarious character actress who played the medium in Noël Coward’s Blithe Spirit but was equally perfect as the addled Miss Prism; and Michael Redgrave as Jack. Through this cast, Asquith let Wilde’s artificial dialogue flow uninterrupted by such fantastic images as knights, white horses, tattoos, and dance-hall girls which Oliver Parker contrived to “enhance” the play at the movie-goers expense.

Granted, in the 1952 film, Dorothy Tutin, does seem too old to play the 18-year-old Cecily (she was 22 at the time). And Joan Greenwood’s charm and sexiness, much admired by the English of the 1950s, is lost on me.

Granted, in the 1952 film, Dorothy Tutin, does seem too old to play the 18-year-old Cecily (she was 22 at the time). And Joan Greenwood’s charm and sexiness, much admired by the English of the 1950s, is lost on me.

But Reese Witherspoon is even older than Tutin had been (she’s 26)—but is better at acting innocent knowingly. Frances O’Connor’s Gwendolen is as good (though less plausible as Bracknell’s daughter than Joan Greenwood had been), and Colin Firth’s Jack is fine, too.

Lord knows Judi Dench can do imperious, but Lady Bracknell is a caricature, not a queen, and Dame Judi is not absurd enough (though her costumes are). Dench seems to be trying to make Lady Bracknell a sympathetic character.

Rupert Everett is not “arch” enough to pull off Algernon. Like Dench, his performance is too naturalistic.

In comparison, the 1952 version still looks fine. It sounds better, has a better cast, reflects a better appreciation of the original script, and holds confidence that Wilde’s situations and lines are enough to entertain the audience.

The 1952 version does waste time at the start emphasizing that it is a film of a play, but it takes the exchanges out of drawing rooms to a range of sets and outdoors. The women have outlandish costumes and cutting lines (some of which were excised from the remake). The men are appropriately befuddled by the women and caught out in their inept sneakiness.

I would readily concede that Wilde’s plot is silly, particularly the determination of Cecily and Gwendolyn to have a husband named Ernest. (Cecily seemingly does not “get” this requirement, though Gwendolyn does.)

I would readily concede that Wilde’s plot is silly, particularly the determination of Cecily and Gwendolyn to have a husband named Ernest. (Cecily seemingly does not “get” this requirement, though Gwendolyn does.)

Edith Evans, as I said, was born—at about the same time as the play was written—to deliver Lady Bracknell’s lines and to look askance at most everything the other characters say. The handbag subplot becomes worth it just to hear Evans enunciate the word. Although she could play working-class characters, such as Richard Burton’s mother in Look Back in Anger and the hallucinating old lady in The Whisperers, Evans is most delightful here, employing a plummy diction that turns one-syllable words into four-note melodies while delivering withering looks.[1]Evans was 64 at the time, and Earnest was only her third sound-film. Three years earlier, she gave us a chillingly memorable performance as the old countess in Queen of Spades. She only started … Continue reading

This should have been reason enough to leave well enough alone and not make another version of Earnest.

If Parker wants to make more movies, he should make original ones, not muck up classic plays (Othello and Wilde’s The Ideal Husband before Earnest). Dude, the language is the thing! If you don’t think the language bequeathed by Shakespeare and Wilde is adequate, then go visual and make music videos—or original stories all your own.

published by epinions, 1 July 2002

©2002, 2016, Stephen O. Murray