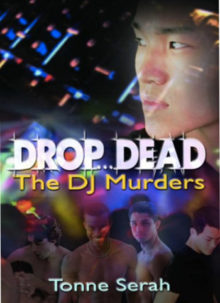

Drop Dead:

Drop Dead:

The DJ Murders

by Tonne Serah

Published by Harrington Park Press

Published January 28, 2007

Fiction

187 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com • WorldCat

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

June 7, 2007

More important than answering the “Whodunit?” question in Drop Dead: The DJ Murders, is the wry new voice of Tonne Serah (a pseudonym), observing the lifeways of some Asian American in a San Francisco club scene in which sex has lost its primacy in the trinity of “Sex, Drugs, and Dance Music.”

Indeed, sex may have fallen into fourth place, behind Looks (couture/coiffure). “Party drugs,” particularly Tina (crystal methedrine), which make phallicism impossible and literally shrivels penises. “A hard cock is good to find” has become passé as erections have become rare and endurance on the dance floor has mostly replaced sexual stamina as a postmodernist “queer” machismo-substitute.

The “pod boys” fear more than they envy the white boys who try to emulate their smooth skin with wax and razors. These homoerotic Asian Americans coming north up the peninsula are “sticky rice” (sticking to their “own kind”) less out of any concern with political correctness than out of fear of larger beasts who are also presumed to be HIV-positive. The world Tonne Serah portrays involves serosorting based on presumptions about serostatus along with the sublimation of sexual desire into dancing under the influence of “party drugs.”

My sociologist’s interest into the clubbing/partying post-gay world and the portrayal of a general indifference to harm reduction do not blind me to the pleasures of the queenly sardonic voice of the narrator and of the characters or of the black comedy of the intersection of ecstasy and murder in the clubs. Along with showing a scene with which I have little familiarity, there are many pleasures of the text here, supplemented by sixteen color illustrations by Gina Wick.

The very self-centered “hero” and reluctant detective, Joey De Vera, is a circuit boy from a Filipino-American family in Daly City that includes eight daughters older than he is. Age is a keen concern to Joey who is so deep into the twilight of his 20s that he is pained by losing a day crossing the International Date Line en route to a family reunion in the Philippines.

At the start of the novel was happily living in “the fast lane life of sex drugs, Diesel jeans, and all-night dancing. Joey’s only worry was what to drop and when. And which white boy he would allow to worship him that night.” He loathes “rice queens” (non-Asians who desire Asians) and “sticky rice” (Asians who desire Asians), so finding a long-term relationship (which, in circuit boyz conception is three weeks) is not easy.

Then, on consecutive weeks at the Club Universe (here akaed Klub Galaxy here, as the Pleasure Dome is thinly disguised as Joydome), DJs drop from the booth where the provide barely danceable mixes literally at Joey’s feet.

Just two weeks ago, he had been a simple circuit boy—the center of his own galaxy [not to mention dancing dead-center at the Klub Galaxy], absorbed in his hopes, dreams, and infinite pet peeves. Now he was the center of other people’s attention, witness to a murder, maybe a suspect—on the front page with bad hair.

The murder mystery is more like Prime Suspect than like Agatha Christie, or like Prime Suspect injected with 1970s “paranoid thriller” content. There is a conspiracy involving law enforcement personnel and a “War on Drugs” by means of ensuring that the “party drugs” are impure. Prohibition of drugs leads the clubs to pretend that the drugs are not used on-site, so that harm-reduction measures cannot be taken (because having them would acknowledge the reality of the drug use).

Joey is a graduate of Berkeley (working for the soon-to-fail (mis)accounting firm of Arthur Anderson) and seems there to have absorbed some post-colonial buzz, which spills out after a web-surfing orgy prior to his visit to the Philippines. I find some of this difficult to credit, and, even beyond the post-whatever modifications of English spelling (heaving on k’s and z’s), there seem to me to be a number of typos (such as “here” for “there,” since “here” makes no sense). The single Tagalog words borrowed in the text are easy enough to decode, but Tagalog sentences are not.

Like Armistead Maupin’s various Tales of the City, Drop Dead was first published as a serial—an on-line one rather than in a printed newspaper. Drop Dead is also similar in having a large number of characters, though a much higher percentage of them are gay (or post-gay, heavily medicated males who dance with males) and more difficult to read because of the slang (circuit and Tagalog). And Drop Dead has a clearer political agenda. The author (who is older than Joey) “lives to dance” but was active in Dance Safe in San Francisco (work for which he was canonized by the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence as Saint Vera Severa).

First published by epinions, 7 June 2007

©2007, 2017, Stephen O. Murray