A Tribute to Drew Robert Shafer

Founder of The Phoenix Society for Individual Freedom in Kansas City, Missouri

by Michael Pfleger, aka “Mickey Ray”

Submitted August 29, 2015.

Yes, Virginia…Sally, Ben and Jerry, there was a politically gay life before Stonewall. I had a small part to play in the year before that historic moment. I even got to march in New York City in the first Gay Pride parade, in 1970, but more significantly, I was involved because I met the man, who three years prior to that date, had started the first “homophile” organization in Kansas City, Missouri.

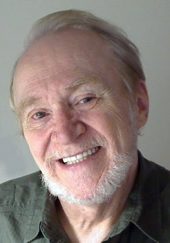

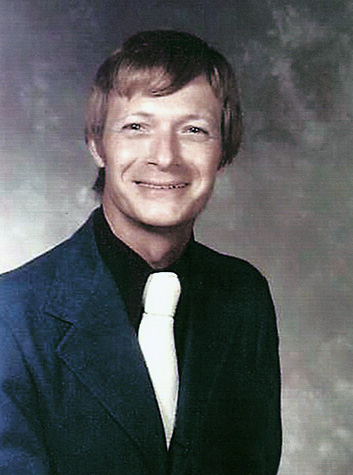

His name was Drew Robert Shafer. He was a wonderful, giving, and farsighted individual that I am very proud to say was my lifetime companion, mentor, and friend for 21 years. He started a homophile organization in Kansas City in 1966, and it was called The Phoenix Society for Individual Freedom.

An only child to Phyllis and Robert Shafer, Drew grew up in a white, middle-class, liberal family. Spoiled to the bone by his mother, he pretty much got whatever he asked for, and although a loner for much of his childhood, he lived a happy, unfettered, carefree life. He recognized he was gay in his early teens and immediately acted on it. He became less shy. He was tall, lanky and outspoken, and he had a wonderful speaking voice. He found early in life that he was able to get others to see his point of view fairly easily. His family followed the practices of The Unity Society, which was more of a positive thinking society than a religious sect. And more than anything else I can think of, positive thinking defined Drew. Nothing completely discouraged this unique man.

He “came out” of his closet wild and willing to try anything once in his late teens, but he was most active in his early twenties, during his college years. His mom ran a boarding house, which was filled with Drew’s gay, male friends. Her “boys” adored her—she was the queen of the roost and loved her position. It was the 1950s; pink was in and Drew wore it a lot. He even had a motorcycle, then a car, painted pink. Yes, his friends called him “Pinky.”

He held dances in his basement and provided entertainment for his friends when there was no place else to go at the time. By the late ’50s into the early ’60s, a couple of the local strip joint owners began to realize the money that could be made from the partying gays in KC. Soon, “The Jewel Box,” “The Colony Bar,” and “The Arabian Nights” opened followed by “The Redhead Lounge.” There was no skimping in decor and atmosphere here. These were beautiful clubs and catered openly to the gay clientele. Kansas City had men dancing in each other’s arms while their sister bars on the coasts allowed no touching on the dance floors!

Naturally, Drew was a big part of that scene, as he was well known in the community at that time. There were always after-hour parties at his house, and he easily made friends with every spectrum of the gay and lesbian community.

At some point he’d become aware of “the movement,” though I cannot be sure what specifically was his turning point to wanting to be politically involved. He once told me he really just wanted to have a club and have fun, but he could not know that so much more was to come of his decision to get involved.

He had, at first, been approached by a California organization called ONE, Incorporated, which had invited him to become a Midwest chapter of that organization. Feeling he didn’t want to be controlled by a larger organization half way across the states, he decided to create one himself. With a handful of friends he did just that. He found a beautiful home for himself and moved the organization in with him.

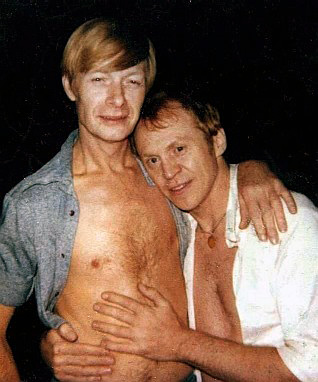

I met Drew about a year and a half later, on September 1, 1968. By chance, I wound up in Kansas City, wondering around, irresponsible and looking for “opportunities.” I’d heard about this organization from a poster I’d seen on the bulletin board of a Methodist Church. They were having a picnic and meeting that Sunday to collect those who needed a ride to the picnic grounds—some private land out in the country somewhere. I met him at that picnic and I wound up with him from that day until the day he died, 21 years and 29 days later.

Kansas City at that time was still pretty hopping for gays—socially speaking that is, because our “family” now controlled the strip bars and clubs. Activities were protected and, in those arenas, gays felt safe to be themselves.

Outside that arena was a very different story. Gay people did not give out their last names. When the organization was formed and got its charter and not-for-profit status, Drew, and his long time buddy, Bill Wynn, were the only ones who used their real name on the papers. As for the media—radio, TV, and the press—only Drew was the spokesperson.

And, like the others, I too chose a pseudonym when I joined the organization. Not out of fear, because I was also openly gay, but as you can see under the title, my actual last name is a fright to pronounce when it’s seen in print and nearly impossible for people to spell when they hear it. That is when I chose the name Mickey Ray. It has been my name ever since and I use it for all my creative aspects from theater (when I was with Equity) to puppeteering, artwork, and writing.

When I met Drew, he had been making a very good salary (at that time) working in both the office and warehouse of Caterpillar Tractor Company for nine years. Shortly before I met him, he’d announced to his blue-collar coworkers and fellow union members that he was going to be on a radio talk show, but he did not tell them the topic of discussion. Curious, almost everybody tuned in and almost as immediately he was nearly fired from his job when he “came out” to the world on the radio!

Very conservative and highly incensed, his boss was livid and did his best to get rid of Drew. However, the United Auto Workers union told management that what Drew did on his own time was not work related and it was his personal business. Caterpillar could not fire him! His job was saved, and he the organization survived their first major hurtle. He would still have to deal with stupid remarks and rude behavior from a few of his more hard-nosed coworkers for years, but he never let it rattle him.

Drew’s dad was a printer by trade. Retired, for the most part, he gave Drew one of his presses, which was in the basement of his three-story house on the corner of Linwood and Paseo streets. We had a core group of volunteers who made up the paper’s creators with Drew teaching us the mechanics. Using old linotype machines, paste-up-boards, and hand drawn graphics, even to photographing and burning metal plates to print from, we created a monthly newsletter. It was called The Phoenix, of course. Ads weren’t hard to get with anywhere from six to eleven bars going at any given time.

Before long we got the attention of other, larger Gay organizations, like New York City’s Mattachine Society, and very quickly, “The Phoenix House” would become a centralized, information clearinghouse as well as distributor for other gay magazines around the ‘gay’ USA from NY to California and even some foreign groups.

Talk about your monthly envelope stuffing!

It was a busy time, and things were going well until we began getting media attention. The gay “community,” afraid of the attention drawn to it, feared reprisals. A sharp division was drawn between those who believed we had the right to be open and be ourselves and those who wanted to keep the protected status quo. It was now the spring of 1969.

The “family-owned” bars started pulling their ads, and many gays were avoiding anything to do with the pariah of the “dangerous” Phoenix Society. There were, however, out of the burning fires of change, a few stalwart gay men and women who decided to try and open their own bars. It was the beginning of a new era. Kansas City gays were now becoming an independent and vocal voice. Only months later, Stonewall would become the marker and song from which Gay and Lesbian activists would march.

Wishing to be second to no one, politically, the Phoenix Society organized marches in Kansas City as well. In conservative Missouri cities like Columbia, we had eggs tossed at us, and we were warned that if we tried to march in Jefferson City, the capitol, they would provide us with no protection from opposing factions at all.

We became important enough for people like Anita Bryant to visit Kansas City and campaign against us in our large downtown auditorium. What a grand “anti-Anita” demonstration there was that day!

Things were changing fast. The local Methodist Church was still one of our staunchest allies on the straight community. However, it wouldn’t be for another five years before PFLAG was on the scene and Drew’s mom became a PFLAG member. Nationally, it was a turning point for gay women as well who were demanding recognition for their contributions to the movement. The challenge was on to make the movement one of Lesbians and Gays as opposed to just the Gay movement which then implied it was run only by activist gay males. The gay country was changing for the better, but not without the wounded. The Phoenix Society was falling apart.

Sadly, with its advertisement income withering, the paper could barely pay for itself, and no income from it could ever cover the costs of maintaining the expenses incurred maintaining the large home that Drew had been generously donating. (The organization never had to pay rent, electric, oil heating, or water, and it used up the entire first floor and basement.)

We lost the house because we just couldn’t afford to keep it going. The organization suffered because there was no place else it could go, and no one else was willing to take up the mantle of leadership.

By 1972, Phoenix was no more.

Both the house and the organization were Drew’s pride and joy, but he’d gone into debt to the tune of over $50,000 dollars in order to keep it going over the years. The supposedly “rich” guy I thought I’d gotten hitched to was poorer than I was; and I had nothing.

A positive thinker always, at least he still had a good job. We wound up living in the basement of his mother and father’s home and eventual bought a mobile home in a park outside of the city. By then, I’d been working almost steadily in Dinner Theater productions within Kansas City and touring around the Midwest and Southwest. It took us almost fifteen years to finally get completely out of debt.

Sadly Drew wouldn’t live to enjoy it.

The summer of 1986, I had joined as a volunteer for an AIDS hospice, and all of us were required to take the test for HIV. Drew decided he wanted to come with me. We took our tests together, but his result came back positive. It was the first time I’d ever seen Drew truly bleak about anything. He was very frightened, incredibly not for himself but for me. The primary breadwinner, he was concerned for my future if he weren’t around. (Actor’s don’t exactly have a lifetime secured position.) Still, I set about assuring him that he wasn’t to worry about such things because I wasn’t planning on him going anywhere.

The first year, he showed no symptoms, and soon was his old self again. During the second year he’d begun to lose energy and his skin was constantly plaguing him with odd fungi or blotching and itching. He was loosing a great deal of weight. He was put on AZT, the “medicine of hope” back then, but instead of helping him, it was poisoning him and he began to need monthly transfusions. He stopped taking the drug, but by then he’d become irreversibly sick. He had to leave work, but fortunately he had excellent health benefits which paid for his medical care. And although he was no longer physically working there, by union rules they could not fill his slot until he decided to leave permanently. He had just completed thirty years of working there, so he could decide to retire if he so chose. He did decide to take his retirement and let them hire someone else. He’d faced the fact that he was not going to return to his job.

Drew stayed in our home, frail and week and on oxygen, until the 29th of September. He’d tried to get out of bed on his own to use the bathroom when I suddenly awakened to the noise of his falling. I immediately called for the ambulance. Drew was white as a sheet and could hardly say anything comprehensible. My baby was 6′ 2″ tall, and he now weighed less than one hundred pounds. He was practically skeletal and, incredibly, the ambulance drivers would not help me get him out of the bathroom. I had to physically lift him and carry him to the stretcher in the living room.

I then had to threaten their boss over the phone with a lawsuit when the driver said I couldn’t go in the ambulance with them to the hospital. I wasn’t about to leave him alone with these Cretans that were afraid to even pick him up! Convinced I wasn’t kidding, their boss told them to let me ride along. It was a very quiet and intense ride to the hospital. Drew had lost consciousness.

I went with him into the emergency room. I told gave them a list of what medicines he’d been taking and what his history was—something Drew could not physically have done had the ambulance taken him alone. I left them to do their work and went to call some of our friends. I knew then that Drew would not be coming home this time and, frankly, I needed a shoulder myself.

The next morning, on the 30th, he was sitting up, transfusion pink and smiling. Would I bring him a newspaper and his slippers? Of course of would. In Drew’s mind, this would be just another day of dealing with his disease. I left and came back a few hours later. The nurse greeted me at the nurse’s station and told me he’d suddenly turned for the worse. She said he’d been calling for me. When I came in, he was already pale and spitting blood. He turned and looked at me with a weak smile and cried that he was “so sorry,” and kept trying to apologize as though he was being an inconvenience. It took every bit of strength I had not to let him see how sad, lost, frightened, and miserable I was feeling. If he was going to leave me, I was not going to let him die worrying for me.

Close to six that evening, at his bedside, I talked to him about letting go. I constantly reassured him I would be fine but not if I thought he was in pain and suffering as he was. I told him I loved him over and over again as I wiped blood from his lips and chin that he kept spitting up. I must have used dozens of hospital cloths and, after awhile, I stopped looking to even see if his blood was getting on me. He was very silent for a few brief moments; then he looked right at me and I watched him leave. It was the first, and hopefully would be the last time I’d ever have to watch a loved one leave their body. I closed his eyes.

Drew died of AIDS September 30, 1989; twenty-nine days after our twenty-first anniversary.

A couple of years later, in the movie Long Time Companion, there was a scene in which one man talks to his dying lover much in the same way that I talked to Drew. When I saw that scene I felt invaded, as though someone had recorded everything that had happened. I must have cried buckets. Then, I realized, of course, that the same scenario was now being sadly played out all around our country and the whole world.

Hurting hearts aren’t very different.

Drew loved gardens and flowers, particularly roses. Per his wishes, I had an outdoor memorial gathering in his name in the rose garden at Loose Park in Kansas City. He was cremated, and his ashes were spread out in a beautiful and specifically designated area of one of the Unity Villages many rose gardens.

No one smiled so often, tried so hard to please and kept his chin up in the worst of times like he did. He changed me from a cold, wondering opportunistic kid into a caring man and convinced me that there is indeed such a thing as a loving relationship. Love can exist and grow between two men as well as any other couple.

Drew taught me that love was a real thing, not just something invented by Hollywood and playwrights. He showed me by example the values of honesty and integrity, and to have the courage to be myself; values I’d far too often missed seeing as a child. His loss was devastating to me at that time, but his memory and lessons now make him live on in my heart and mind.

The last movie we watched together was Beaches. He always was “the wind beneath my wings.” I will love him and miss him for as long as I live.

Sincerely,

Mickey Ray-Pfleger

©2016 by Michael Pfleger. Reprinted with permission. All rights reserved.

Also see: “Drew and Mickey meet: a little more history,” by Mickey Ray