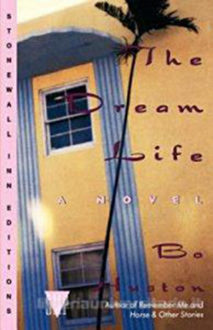

The Dream Life

The Dream Life

by Bo Huston

Published by St. Martin’s Press

Published October 1, 1992

Fiction

165 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com • WorldCat

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

June 17, 1998.

Bo Huston (1959–1993) died of AIDS complications soon after the publication of his second novel, The Dream Life, in 1982.

Neither of the alternating narrators is HIV+, though the elder one has a chronic cough, making it harder not to read the author’s situation when he was writing into Hollis “Holly” Flood. Holly does not appear to know his HIV serostatus, but given his past I find it more shocking that he engaged in unprotected sex with the boy who ran off with him than that someone around thirty years old had a sexual relationship with a boy of fourteen…until the boy outgrew his mentor.

Both near the start and near the end of the short novel—it’s 165 pages, some of those blank—there are references to Death in Venice, a novella in which a man in his late 50s pines for a pubescent boy as a cholera epidemic sweeps through town. The love in The Dream Life is mutual and requited and with a significantly smaller age gap. It seems to me more akin to Lolita than to Death in Venice in that the mother of the youngster thinks that the teacher (Holly, Humbert Humbert) is interested in her rather than in her child and that the adult takes the young loved one on the road across America. A Las Vegas hotel house detective does not make much of a Quilty, the mother is not killed off as Lolita’s was, and, at the start, Jed is more isolated and inexperienced than Lolita was.

At the start, Jed Levine refuses to go to school anymore because he has no friends. He is bored more than persecuted there. His mother hires Holly to tutor the thirteen-year-old boy. Holly commutes into the affluent neighborhood by bus at 6:30 in the morning with housemaids. There is no set curriculum, and no mathematics, but Jed learns a lot and becomes an eager learner in part because he is infatuated with his mentor, the only person who pays attention to him.

If Jed’s father is alive, he is nowhere around, and his mother, who is working through a succession of husbands, has little interest in Jed and (in both Jed’s and Holly’s view) does not like Jed but increasingly flirts with Holly: “It was astonishing to watch this woman construct our cozy friendship entirely on her own. I was less than encouraging, stony-faced and withdrawn.”

Uncomfortable with her advances, Holly decided to leave, and, uninvited, Jed decides to go along. In Jed’s portrayal:

It started out Holly talking about himself, wanting to move, needing to go away and me being sad and confused, mad at him. Then it was just assumed somehow that I would go along with Holly. We were not done with each other. It wasn’t time for us to be apart…I loved Holly. Everything that’s happened since, anything people want to say or think about me and Holly, all of how it looks or seems is irrelevant to me. I really loved him. I wanted to be with him.

Jed’s mother reports her son kidnapped. She is more embarrassed than concerned about her son. Still! Even remembering my own keen desires at age 14, and not sharing the current and recent American hysteria about “sexual abuse” of minors, it seems to me that Holly takes advantage of Jed’s hunger for affection when they start having sex and of the monopoly of Jed’s time that started at home. If I am repelled by how Holly takes advantage of and profits from Jed’s inexperience and neediness, I think that most American readers would be so overcome with repugnance at “sexual abuse” that they would simply condemn the book.

I am not especially interested in the psychology of pederasts and the boys who love them, though I know that 13–15-year-old boys are generally obsessed with sex and that more than a few are sexually active with others and more, like Jed, heavy into masturbation. And I know that some of these hormonally supercharged boys prey on the neediness and hunger for physical contact of those keenly feeling that they are no longer young. Many live dangerously, and some die young.

There is more pedagogy than pederasty in the relationship of Jed and Holly. Jed is developing into an artist, photography being his medium. He learned a lot from Holly, who had hustled L.A. as a boy, including sexual techniques. Unlike many young prostitutes—male, female, transsexual—he had already had a childhood, if not a particularly happy one. And like many of the “victims” separated from their “abusers,” he still loves Holly. Jed’s breaking out a second time is like the first in that he feels he is not getting enough attention and love, increasingly feeling neglected by Holly, feeling that Holly has tired of him.

I was simply afraid that Jed was maturing, getting smarter and healthier and stronger, and that he would inevitably go away. Like what poor Rev. Dodgson must have felt with his tough little Alice—a terrible unrequitedness, a sorrowful certainty that he is only another game to outgrow.

No one gets shot before, during, or after Jed’s escape with Holly, so the book is more un-American than Nabokov’s which eventually gets around to gunfire—not to mention that the pederasty there is heterosexual. The tragedy for the adult pederast is that the one they love grows up, outgrowing their desirability, and as often growing indifferent to the elder partner as nursing grievances and feeling traumatized by what happened. Holly does not despair that he has lost his Lolita. He pushes Jed away before Jed feels he has outgrown his mentor. Holly is not desperate to hold or to find Jed after Jed leaves, as Humbert Humbert is.

Holly’s glum self-awareness, not least of his amorality (“I know nothing—not what I want, or what is possible or moral or true”) is convincing. The danger of an adolescent narrator being too wise is not avoided. Granted, he has had intensive tutoring, read a lot under Holly’s guidance, acquires much experience between the ages of 13 and 15, and has been much influenced by Holly. Still, his voice seems to me too much like Holly’s: too literate, too adult…too much like Bo Huston’s as I recall it in his [San Francisco] Bay Times writing of the late 1980s.

There is some overlap with both narrators recording their accounts of a few events, but mostly the story advances—once it gets going—with one taking up where the other left off and the first taking up where the second left off. This strikes me as phony.

Though in several senses Jed is a child, he is also something of a seducer and an adult molester and, having left Holly, does not regret their time together but is grateful for it and for what he learned. I regret that Huston did not live to develop further. There are some vivid scenes and two interesting characters in his last novel, even if the plot sometimes strains credulity and there are some overwritten faux-poetic, faux-philosophical passages in Holly’s chapters.

And neither Jed’s story nor Holly’s has an ending. Like New Yorker stories, they just cease.

The Dream Life won the 1993 Lambda Book Award for gay fiction. Posthumously, he won the same award the next year for his collection The Listener.

I was, however, disappointed by the novella and stories posthumously published in 1993 in The Listener. It seems to me that he set up characters and situations well, but then didn’t deliver payoffs. The cataloging as “Mothers and sons-California” is somewhat apt—at least for crazy Jane and her abused part-Indian son Russell, though I think the titular novella is set in Oregon, since it doesn’t usually rain in the summer in California. The depressed gay men (one accused of child abuse, one “home” with AIDS, two mourning friends) like ice cream, need coffee and cigarettes, don’t like earth tones. Only one of them interacts with his mother, however. A sister who leaves her abusive husband in New York then goes back to him is the recipient of Paul, whose lover recently died of AIDS and is cabin-sitting somewhere north of San Francisco.

The novella and the four stories are like New Yorker fiction in stopping rather than having endings. I detest “A Better Place” (centered on a new third-grade teacher in the desert West, having difficulties of various sources adjusting to having left her familiar New York world). I liked “Freud’s Big Problem) but liked even more “This Is Not That,” in which a gay male character has fled accusations of inappropriate touching (none of the pedagogical eros of The Dream Life!) and is pestered by an alcoholic woman who has just been fired from her job. I also thought “This Is Not That,” a story told from the perspective of a widowed mother who prefers the prodigal son to the dutiful daughter. The slender “My Monster” is mildly entertaining (devoid of sex, though having a last-minute dollop or eros).

It’s depressing that Huston didn’t have a chance to develop further.

© 17 June 1998, Stephen O. Murray