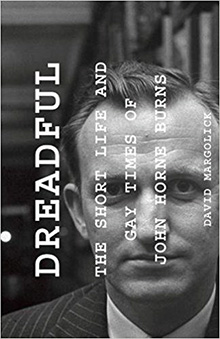

Dreadful

Dreadful

The Short Life and Gay Times of John Horne Burns

by David Margolick

Published by Other Press (reprint ed.)

Published November 11, 2014

History (biography)

480 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

July 10, 2017.

There was a fellow who wrote a fine book and then a stinking book about a prep school and then just blew himself up.

—Ernest Hemingway’s synopsis of John Horne Burns

The title of David Margolick’s 2013 biography of novelist John Horne Burns (1916-53) is a double entendre: Burns was a rather dreadful human being and used “dreadful(s)” as a code word for homosexual(s).

Burns was “dreadful” in the second sense, though more a dropper of “hairpins” in life and in his books than an out gay man. Those “in the know” easily recognized the homosexuality not quite explicit in text or public appearance.

“Gay Times,” in the subtitle “The Short Life and Gay Life of John Hornes Burns,” only means trying to glimpse Burns’ homosexual (far from “gay”!) life in the U.S. and Italy (where he was stationed in the latter part of WWII and where he eventually died), not the kind of focus on the times in which the biographee lived of “life and times” biographies.

Burns’ sister, Cathleen, long blocked published quotation of writer’s voluminous correspondence and diaries. The brother, Tom, to whom rights devolved, was also reluctant for the gay material to be made public, but eventually agreed, after reading the material.

Having been a restive teacher at the private boys’ school that Margolick later attended (Loomis, in Windsor, Connecticut), Burns was drafted in 1942. His fluency in Italian and German resulted in him being assigned to military intelligence in Casablanca and Algiers, censoring letters (at first of Italian POWs, later of GIs) rather than sent into combat.

He wrote a series of vignettes (more a collection of stories than a novel) about occupied Naples, that was published to much acclaim as The Gallery in 1946. Though showing American soldiers abroad, The Gallery is a “war novel” about rear echelon military personnel, mostly off-duty, and observations of the desperately impoverished “liberated” population (there was an insurrection against the German occupiers before U.S. troops arrived, so a degree of self-liberation applies).

There are some clear but not explicitly labeled homosexual liaisons across the book, especially in a VD treatment facility (in the early days of penicillin). The gay bar in the Galleria Umberto I, Momma’s, is also never referred to as a gay bar, though it is a place in which men hook up with men, women hook up with women, and there is much carrying on (“letting down their hair”). There’s even a typology of (three) kinds of homosexuals. It was written from the patronizing distance that Proust also adopted in Sodome et Gomorrhe (1922).

Burns expressed a “hope that out of the war, and the species of horror either invented or refined during it, will come a new code, one permitting this repressed but irrepressible portion of humanity to surface and prosper without any adverse judgments attached.” Yet, he wrote of the lives of homosexuals as “centrifugal, horrifying, and deathmaking.”

Though Burns was not a writer with much imagination, Margolick concludes that there was not a gay bar or proto-gay-bar in the Galleria Umberto I, so that the chapter “Momma’s” is not reportage. There was the boys’ school to which Burns returned for a year after being discharged and the savaged/ridiculed characters in his second published “novel,” Lucifer with a Book were easily recognized by those in the know about Loomis staff. Critics savaged the book, and Burns left the U.S. in 1950, settling in Florence and more or less drinking himself to death at a corner of the Excelsior Bar, discouraging approaches by anyone.

A third novel, A Cry of Children, was published in 1951, which ended the three-book contract made to obtain The Gallery. The draft beginnings of a fourth one was rejected by all the publishers who looked at it.

Margolick praises the pieces on Italy and North Africa that Burns wrote for the upscale travel magazine Holiday. He makes me wonder if they might be of lasting historical interest in collecting and publishing them.

Burns was a “one hit wonder,” and the one “hit” was a very uneven collection of anecdotes and impressions, written with compassion for most of its characters. Burns’s estimation grates:

[It] is, I fear, at least as good as War and Peace. I have a little bet on with myself that I’ll make every American writer up till now look sick.

His superiority complex (as usual, covering self-hatred) and alcoholism make Burns an unsympathetic character and the internalized homophobia and necessary closetedness that fed Burns’s rage and drinking make him a tragic figure (to understand all is to forgive all).

Margolick does not defend Burns’s conduct, nor did he set out to write a “pathography.” Explicating the conduct necessarily resulted in chronicling a case study of pathology/ies.

It is very irritating that the book lacks an index or any documentation. I’m curious about the Gore Vidal diaries Margolick quotes and don’t find the quotations from Isherwood’s well-indexed diaries. I’d also like to know who characterized Burns as “about three-quarters skunk and one-quarter rattlesnake.”

©2017, Stephen O. Murray