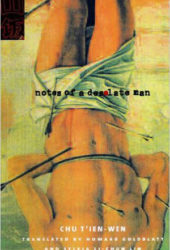

Notes of a Desolate Man

Notes of a Desolate Man

by Chu T’ien-wen

Published by Columbia University Press

Published November 15, 2000

Fiction (world literature)

184 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

May 1, 2000

Notes of a Desolate Man is an annoying, bleak, postmodernist Taiwanese novel by Chu T’ien-wen that, for reasons I can’t imagine, won the China Times Prize in 1994 (or why the Columbia University Press published a translation of it in 1999).

Like Christopher Coe’s I Look Divine, a much better short novel (out of print, alas), the book is the reflections of on gay man about another who has died. (Unlike Christopher Coe’s book, Notes was written by a straight woman.)

In Divine, they are brothers, and the one who died died of narcissism. In Notes, Ah Yao dies of AIDS in a Tokyo hospital and is recalled by his friend Xiao Shao. Divine is tightly focused, a récit. Desolate is all over the place, in which brittle reminisces of Ah Yao are mixed with lots or pretentious high-culture babbling (on the page: jottings).

Both books have far too much in common with the doomed homosexual mode of the 1950s in which the homosexual must die, preferably a grisly death. That is, BTW, the era in which the most famous Taiwanese novel about doomed young homosexual men, Nie Tzu (Crystal Boys) was set.

Xiao’s story (as imagined by a heterosexual woman writer) invokes not very interesting or original musings about being gay, about sex, love and friendships (and how these are distinct from each other) and about loyalty and duty within Taiwan’s/East Asian/Confucian sociocultural assumptions and interpretations.

Xiao is a sad and lonely homosexual of the old school, seriously considering marrying a woman to escape loneliness—without giving much consideration to the confusion and dissatisfaction women married by covert homosexuals feel and blame themselves for. At age 40, he considers himself an “old crocodile”—another similarity with the rabid internalized ageism on display in You Look Divine, though instead of suicide he dabbles with various folk medicines to combat wrinkles, balding, and sagging flesh.

Ah Yao was an activist involved with ACT-UP. Contrary to the widespread stereotype, Ah Yao did not dote on his mother. Rather, like Edward Albee, Scott O’Hara, Gore Vidal, and quite a few other gay men, he despised his mother.

Why a fairly long-term relationship—with a budding film-maker named Yongjie—ended is unclear in Xia’s mind and musings, though a better question would be why anyone would have spent seven years with Xiao. After Ah Yao, Yongjie left Taiwan to make his fortune elsewhere (Japan and China respectively), Xiao moped about aging and resented the young and practiced sophomoric cultural criticism in his notebook.

Xiao is close to being totally implausible to me as a gay man, even a homophobic gay man. The book is very much a set of women’s conjectures about what being a gay man might be like. There are female writers who have created first-person gay male narrators I find plausible (Patricia Highsmith, Mary Renault, Marguerite Yourcenar), but this deracinated Chinese woman is not so imaginative. Most of the book is ignorant musings on College de France theorists (Michel Foucault and Claude Lévi-Strauss), pedestrian musings about art house films beloved by would-be cosmopolitan students of the 1960s, along with flashes of regret for a gay Taiwanese friend’s excesses, which the author seems to feel are justly punished by a grisly AIDS death.

For a 166-page book with few words per page, this seems very long and very tedious read. The pleasures and insights are very few. Anyone who wants to read about desolated Chinese homosexuals lost on Taiwan and doomed by convention to suffer and die young would do better to read or reread Pai Hsien-yung’s melodramatic 1983 novel Crystal Boys instead [or, now Beijing Comrade, the basis for the film Lan Yu.]

I do not consider Notes of a Desolate Man to be “gay fiction,” though it is fiction about a gay man, one supplied with what might be interpreted as “internalized homophobia” by anyone unaware that the character is not autobiographical and was not written by a gay man.

published on epinions, 1 May 2000

@1999, 2016, Stephen O. Murray