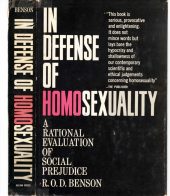

In Defense Of Homosexuality:

In Defense Of Homosexuality:

A Rational Evaluation of Social Prejudice

by R. O. D. Benson

Published by Julian Press

Published 1965 • Psychology

xiii, 239p., introduction, references

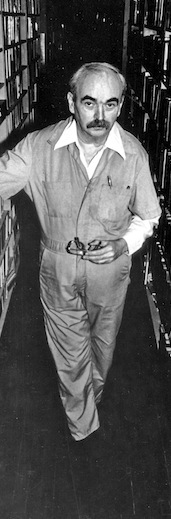

Reviewed by Jim Kepner

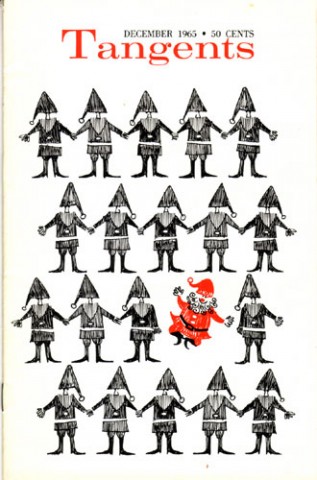

Originally published in Tangents, December 1965

Despite minor but persistently annoying flaws, this is one of the really important books in the homophile field. Noting that man can modify his life and condition by giving thought to his problems, Benson, about whom we are given no personal data, aims “to provide the homosexual with a philosophy that will enable him to come to grips with his life and not feel guilty over his life-choice of homosexuality.”

Despite minor but persistently annoying flaws, this is one of the really important books in the homophile field. Noting that man can modify his life and condition by giving thought to his problems, Benson, about whom we are given no personal data, aims “to provide the homosexual with a philosophy that will enable him to come to grips with his life and not feel guilty over his life-choice of homosexuality.”

He presents complex and technical propositions with unusual clarity, lamentably high incidence of miserably bad usage and grammar, some of which, along with dozens of omitted question marks, must be attributed to careless editing. Perhaps in a later edition these things will be cleaned up.

Mr. Benson deals first with the view that homosexuality is unnatural. With sharp observations about such “laws of nature” as that man cannot fly, or that childbirth “should be” attended by pain, he concludes that man by his nature amends the laws of nature, that nature provides no ready moral guide to human action, and that man in part creates his own world, imposing on nature his own values. And in man’s world, pleasure is valuable for its own sake. Nor do we find any universal measure to determine which values should have precedence. The charge, he concludes, that homosexuality is unnatural is groundless.

Turning briefly to religion, he ignores those lines of Biblical, historic or theological argument by which homosexuals might seek Judaeo-Christian justification, and deals , soundly enough, as far as he goes, with the few passages of scripture that condemn homosexuals.

Besides the assumption—which many will no longer concede—that the Bible is God’s word, it is further assumed that the word is so transparently clear that everyone can know its meaning. But interpretations of even the “clearest” passages vary widely. Benson argues that Christians believe just those parts of the scripture that suits them. While accepting anti-homosexual passages, they casually ignore (as obsolete) scriptural dietary laws and commandments to punish such heterosexual sins as adultery by death. Unfortunately, he evidences no familiarity with the positive literature in this area, and he underrates, I feel, the pervasiveness of religious influence.

He shows no such superficiality in dealing with psychology—here he displays a sound mastery of the literature, pro and con, and in incisive manner of criticism. The best of the sciences are not so accurate, he says, as laymen suppose, and personality theory is indeed far from being solidly established. Psychological theorists can rarely agree on any level, even in reporting simple observations of the same fact. (People rarely see the same facts.) Nor do psychotherapists regularly exhibit the cautions and controls generally considered a prerequisite to scientific research or reporting. They widely ignore the biologically established principle that “the same stress does not produce the same reactions in all individuals,” (Benson cites tears as an effect which might have any of several possible causes from sorrow or laughter, to peeled onions) and there is a normal reaction to stress which, under other conditions, might be considered neurotic behavior. (Is it psychotic, or normal, for an American Negro to feel persecuted?) Therefore, Benson argues, we must only attribute particular behavior to a mental disorder if we know the person, his background and his environment rather fully.

Sexual behavior is not limited to the reproductive function, it is learned behavior rather than “instinctive,” and is indeterminate in its object, and pleasure is a valid end of such behavior. Since most men, at least, show potential for homosexual, bisexual or heterosexual behavior interchangeably, he argues that psychological labelling of homosexuality as a sickness is mere value judgment, which cannot be scientifically or logically validated, and means little more than that the analyst personally dislikes homosexuality, and attributes to the homosexual nature certain unhappy personality features appearing in some homosexuals as a result of discrimination.

Then Benson turns to a long argument that, despite its necessity for wrapping up his very sound defense of homosexuality, will still seem irrelevant to many readers. For in order really to evaluate the homosexual position, it is necessary to know more about scientific and logical methodology, and limitations, than the average reader, or most so- called authorities in this field, are likely to know. Since the 188Os, scientists have generally realized (with some thanks to Freud, and some to positivists and semanticists) that it takes more than an assemblage of facts and logic alone to open a closed mind. New ideas are rarely accepted on the basis of argument alone, but must utilize some of the same sorts of non-rational convincers that provide the cement for old prejudices. Often as not, new ideas simply have to wait until a new generation grows up already accepting them.

No matter how sound our arguments are, some decent and intelligent people will simply not be able to recognize homosexuality as normal behavior, so we have to find strategies to circumvent their blindness to facts which don’t fit their preconceptions. Benson suggests we do this by seeking allies, such as heterosexual advocates of contraception, who by analogy can he drawn into empathy with the conditions homosexuals have to put up with. After all, the same arguments used against us are generally put forward against contraception, and both groups suffer the same restraints on free action.

If we have no universal standard to tell us which values are superior or antecedent, we nonetheless have certain pragmatic guides. Homosexuals and heterosexuals alike can be made to see that each man’s freedom to develop his own life as he sees fit depends on recognizing every other man’s right to do likewise. By this rule, the pragmatic yardstick, the categorical imperative, the golden rule, each man must guard every other man’s worth and freedom in order to protect his own worth and freedom, and must abjure all attempts to force others to do what someone else supposes to be good for them.

Homosexuals, Benson says, ought not to seek to get public approval of homosexuality, but acceptance of everyone’s right to make his own life. The battle of the homosexual is part of the greater fight for the right of each individual to find his own happiness.

I think it unfortunate that the author took an unnecessary excursion into opportunist and unscientific reasoning to propose the old canard that swishes behave that way only because the laws are unfair. The molding of an effeminate character, whatever its complex of causes, usually predates the discovery of discriminatory laws. Nor are effeminate displays limited to societies which discountenance homosexuality.

But such diversions aside, this lively and forceful book assembles the sort of valid argument which every self-respecting homosexual ought to have on the tip of his tongue. Buy this book and study it.

©1965, 2016 by The Tangent Group