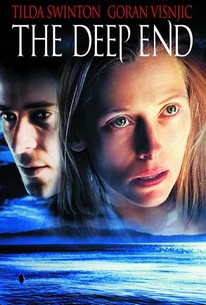

Directed by Scott Mcgehee and David Siegel

Written by Scott Mcgehee

Released 31 August 2001

Drama (thriller)

101 min.

Review by Stephen O. Murray

September 3, 2001.

Like The Talented Mr. Ripley, Deep End is beautifully photographed pulp fiction with some intriguing characters. More specifically, it is like the aquatic parts of Ripley, though being out on Lake Tahoe brings flashbacks to me from Godfather II and A Place in the Sun.

Margaret Hall [Tilda Swinton (Orlando)]wants to preserve the good life for herself and her three children. In particular she wants to protect her 17-year-old son, who is not particularly aptly named Beau, but is well played by Jonathan Tucker.

Beau is giving his mother, who is already stressed from caring for three demanding children and doddering though well-meaning father-in-law [Peter Donat] while her husband is gone most of the time, when Beau starts causing big-time worries. He is nearly killed in a car crash while driving drunk, accompanied by a sleazy owner [Josh Lucas] of a gay disco, called The Deep End, in Reno. (Aside, it’s something of a welcome change for California to be the land of purity and the corruptors slithering in from the east…)

I’ve already gotten ahead of the opening of the movie, which is Mrs. Hall visiting the disco during the day and pleading with Darby Sleaze (OK, his last name is really Reese) to stay away from her son. I can’t remember whether we hear her offer him money to stay away or only hear about it later.

Back from the dust and squalor and vulgarity of Nevada to the elegant home in pristine California, she tries to talk to her son. He does not want to talk about what is worrying his mother. Having once been a proto-gay teenager (though admittedly a long time ago), I can understand this perfectly. My forbidden desires were extremely low on the list of topics I wanted to discuss with my mother, though I was not being porked by a low-life adult (or, for that matter, anyone).

Beau is more afraid of his father learning that he has a gay son than he is of being exploited by someone old enough to be his father. This is crucial datum seemingly missed by some viewers and reviewers. Perhaps I am particularly attuned to it from writing about the pioneering Taiwanese film Nei Zi (The Outsiders) in which several gay sons are expelled from their families and homes by military fathers.

Mr. Sleaze shows up, even while Mrs. Hall is writing her husband with careful indirection about her concerns about Beau. When Margaret finds his corpse in the morning, she just assumes that Beau killed him.

She goes into protective mother overdrive and disposes of the corpse in the lake—in very shallow water of a very deep lake, but that turns out to be a good idea.

Why didn’t she ask Beau what happened? Well, she did not get very far trying to discuss the relationships the previous day and doesn’t want to traumatize him more—more than she presumes he is from having killed a man with whom he’d been intimate. I don’t know if this is how mothers really think (as in the case of A.I., I’d be interested in mothers’ perspectives on this movie), and how little we insouciant sons know of what our mothers do to protect us. I do know that in movies characters often seek to play “out of sight, out of mind” (a refrain of The Talented Mr. Ripley and A Place in the Sun, and, for variety, how about With a Friend Like Harry and Sexy Beast?) and dispose of the corpses of people who were obstacles to their plans.

Aside from the shimmering photography of water (inside as well as outside the house), what is most notable is that the blackmail that then envelops Margaret does not involve anyone having seen her and the corpse. Instead, there is a videotape of Mr. Sleaze plugging a fairly out-of-it looking Beau.

The original story, by Elizabeth Saxay Holding, [1]first published in The Ladies Home Journal in 1947 then as a novel titled The Blank Wall, filmed by the immortal Max Ophuls as The Reckless Moment in 1949 had a daughter consorting with an adult gangster. Had the youth remained a girl, I greatly doubt that anyone would have found the sex scene “graphic.” Like the supposed surfeit of kissing in The Adventures of Felix, this is to me evidence of the extent of homophobia in the U.S. anno domini 2001. But this is a movie review, not an editorial on family values.

Some viewers have also had trouble with the change—or development—of heart of blackmailer Alek Spera [played by Goran Visnjic] when he looks in the oven and sees a roast waiting to be baked. In my viewing, the blackmailer’s heart was not in it from the beginning when he saw Margaret with her younger son, and he doesn’t have an epiphany in (front of) the oven. I can easily supply him a tough childhood to explain his fascination with how Margaret is caring for her children.

I am interested in the calculus that it is better for a married woman to become involved with a felon than for her son to be involved with a businessman—that could bear some reflection, but let’s assume the businessman is also a criminal and rush on. The motif is what a mother will do to protect her young. Tilda Swinton is a worthy successor of Joan Crawford in this, and probably deserves some romance, or at least serious contact with some close to her own age. Alek meets the kind of Hollywood justice that the censors of the Hayes Office made common in the 1940s (the first American version of The Postman Always Rings Twice leaps to mind), so it’s OK, and the Californians live happily ever after.

I am interested in the calculus that it is better for a married woman to become involved with a felon than for her son to be involved with a businessman—that could bear some reflection, but let’s assume the businessman is also a criminal and rush on. The motif is what a mother will do to protect her young. Tilda Swinton is a worthy successor of Joan Crawford in this, and probably deserves some romance, or at least serious contact with some close to her own age. Alek meets the kind of Hollywood justice that the censors of the Hayes Office made common in the 1940s (the first American version of The Postman Always Rings Twice leaps to mind), so it’s OK, and the Californians live happily ever after.

Giles Nuttgens’s photography is gorgeous. This seems to be a year of very insistent color design (Moulin Rouge, AI, Amores Perros, among others, though for wall-to-wall blue eyes I doubt that anything can ever compete with Moulin Rouge). This is a very blue-tinted film. It may be the most daylit film that might be considered in the cinema noire tradition. Since my view is that color is incompatible with genuine cinema noire, let me suggest cinema d’eau. A case could be made for cinema bleue, but there really is water everywhere (except Reno) in this film, including bottles of it that set up a lot, fish tanks, faucet drips, and the majestic Lake Tahoe.

As in With a Friend Like Harry, there is quite a bit of humor (not all of it bleak) in this shimmeringly photographed story of corruption, death, and blackmail.

published on epinions, 3 September 2001

©2001, 2016, Stephen O. Murray