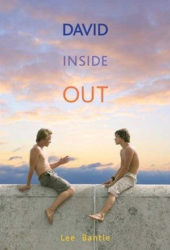

David Inside Out

David Inside Out

by Lee Bantle

Published by Henry Holt and Co.

Published May 12, 2009

Fiction (young adult)

192 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

July 28, 2009

The mention of the Minnehaha Parkway in the first sentence of Lee Bantle’s 2009 juvenile fiction book David Inside Out caught my interest as a native of the Twin Cities and made me wonder when is the present time of the novel with a reference to Archie and Veronica. I hadn’t realized that that franchise, which began in 1939, is still running, so that contemporary high school juniors might make reference to it.

Throughout the swiftly moving novel, I continued to watch for hooks to a particular time. The only clear one was that the mother of the title character (David Dahlgren) danced to the Supremes during the early 1970s, and David makes a remark about things being different from the ’70s when she was young.

The characters have cellphones, and there is a Gay Hotline. An attempt is made by David’s grade school friend, Eddie, to start a Gay-Straight Alliance, so I eventually decided that the present of the book is the recent past with the author’s memories of the stürm und drang of a somewhat less recent past.

The social- and psycho-dynamics are (alas!) timeless. The A loves B, B loves C, and C loves C unclosed triangle is eternal, and the confusion of feeling different, not feeling what the other boys are feeling about girls and feeling what no one else seems to be feeling about boys, along with the high costs of being perceived as “queer” are very little changed from the 1960s, as I already knew from C. J. Pascoe’s excellent high school ethnography, Dude, You’re a Fag (which showed that homosexual sex is neither a necessary nor a sufficient criterion for hurling the epithet).

Translating the algebra (all are juniors in a Minneapolis private school): A is “Kick,” a somewhat plump (“fat” or “voluptuous” in the view of others, “fat” in her own), B is David, and C is Sean, a member of the cross-country team with David. (I gather the school does not have a football team, so the “jocks” of the autumn are on the cross-country team; in the southern Minnesota high school I attended long, long ago, the cross-country runners were almost as marginal as those who did not play any sport.)

Sean hopes (or his father is pressing him) to be captain the next year. The other candidate for team captain, Parker, hangs with Sean but outruns him in the qualifying (for statewide competition) race. Parker is vociferously homophobic. David is unsure whether Sean is flirting with him to expose him or to get it on with him; Sean’s mother more overtly flirts with David.

To avoid guilt by association, David has dropped Eddie, who is a scholarship student like David, and shares an interest in romance novels. (Up through the summer before their junior year, the two write to authors of romance novels, something way beyond being too “faggy” for me even to conceive of 17-year-old boys in a homophobic environment doing.)

Being Minnesota, a snowstorm blows up to strand David and Kick on the way back from a weekend of sexual experimentation. This gets Kick grounded but increases David’s prestige (I presume that the conventional wisdom of my day—“the fat ones f___”—continues) and covers his increasingly pressing desires to be loved by another male.

Kick, Eddie, and Sean all press David to be the boy they want him to be (three different ones). David’s Mom (David’s Dad died when he was five) want him to be himself, but (1) he doesn’t know who that is and (2) is painfully aware that, if who he is is a gay teenager and others know this, things will not be easy for him:

Being yourself might make people reject you. People you desperately care about. Being yourself only works if you’re basically cool. Which I’m not. There’s another problem with Mom’s advice. How can you be yourself if you don’t know who that is?

I guess that, in addition to being about juveniles, what makes this fiction for juvenile readers is short sentences, as exemplified by this quotation. And short paragraphs. I ran together two and a fraction paragraphs from the text. It also has short chapters: 38 in a book of 184 pages.

The characters, dialog, situations, disappointments, exaltations seem plausible to me. As does the local color, including lefse (though the dreaded lutefisk is not mentioned) and concoctions like canned spaghetti on garlic-butter toasted hot-dog buns (nothing with lime jello though) and the very word “hotdish” (unknown in Californiaese: we have “casseroles”).

David is less idiosyncratic a boy than the narrators of the other works of juvenile gay fiction I’ve recently read (Dale Peck’s Sprout, David Cameron’s Someday This Pain Will Be Useful to You, and even André Aciman’s Call Me By Your Name) as well as the Native American juvenile fiction by Sherman Alexie I’ve read (Flight, The Absolutely True Diary of a Part-Time Indian). Although I don’t think that David Inside Out breaks new ground in the coming-out genre, it tells the difficulties in ways that ring true and does not engage in Candide or Pollyanna fantasies that to “just be yourself” will make everything bad go away (and win Prince Charming or his fantasized surrogate).

I think that it is also particularly good at showing (rather than telling) how those who pretty much cannot pass as straight define where the straight/queer border is, making it easier (if still fraught with danger) for those boys “messing around”/“getting off” with other boys to avoid stigmatization and even those who realize that they are gay but sufficiently masculine not to be suspected as long as they have a girl friend (who blames herself at not stimulating the boy who is trying hard to feel what he doesn’t feel or is relieved at the lack of sexual pressure from the boy).

I’d wish that such a book had been available to me when I was 17, except that I would not have known to look for it. I was definitely in love with a high school athlete (who lettered in three sports as a junior) but didn’t infer anything like an identity for another five years. I didn’t know what I wanted from my best friend and constant companion, so how could he? especially not having the same feelings for me…

My class did not have a “class queer,” though the class above and the class below mine had targets of abuse (and I got in trouble for some derogation I’ve forgotten, but I did not see or want to see any basis for solidarity and had a small share in perpetuating the stigmatization of boys without conventional masculine interests and in maintaining the border of “normality” one of gender rather than erotic feelings).

Sex happens among teenagers (ask Levi Johnston and Bristol Palin). The sex that happens to David (which is not what he hoped for) is recorded discreetly but not opaquely. There is little “street language” except the epithets hurled at those boys seemingly lacking in proper masculinity and heterosexuality. Not that discretion will keep the book from being a target of book banners eager to prevent troubled teenagers from reading “You are not uniquely bad: others have feelings and experiences similar to yours” rather than “People like that kill themselves.”

published on epinions, 28 July 2009

©2009, 2016, Stephen O. Murray