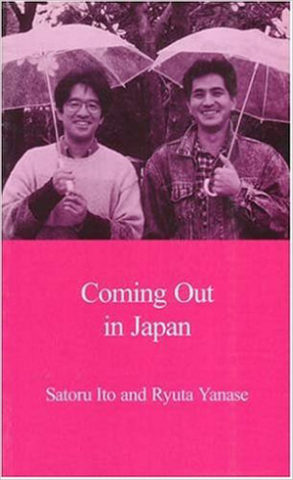

Coming Out in Japan

Coming Out in Japan

by Saturo Ito and Ryuta Yanase

Published by Trans Pacific Press

Published January 1, 2001

History (memoir)

400 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

June 19, 2001

I really wish that I could recommend Coming Out in Japan, because it is a tale of working through embarrassment at being different, and the authors are pioneers at high-risk activism. Alas, I cannot.

The authors are Japanese gay life-partners who went public about their gay identity and relationship. Satoru Ito, the senior author, a schoolteacher, has written a number of books challenging the Japanese education system. He published Two Men Living Together: My Gay Pride Declaration in Tokyo, 1992, and a series of article about being gay in Japan. In 1994, a second book with Ito’s memoirs and those of his partner, a younger carpenter named Ryuta Yanase.

Serialized, the repetitions were probably bearable, but in book form, they are not. Most everything is told at least three times by each of them over the course of the book. In that their experiences are not very different from those trying to come to pride in being gay in places where gays are invisible, the points do not need to be driven home and driven home and driven home. It is all too true:

All homosexuals, regardless of how they individually take the shock of learning of their sexuality, will at some stage will experience a sense of self-rejection. They reject themselves because they see themselves as something that they believe should not exist—something that should not be allowed to exist. And some homosexuals can believe that they are alone in this world—that there are no others like them to be found anywhere.

Ito and Yanase are candid about their despairs when each believed himself to be the only male with erotic feelings for other males, about attempting to simulate heterosexual males at school and at work, about trying to keep too busy to have time for love and desire, to shut off any feelings of any sort and, in Yanase’s case, any significant contact with other human beings.

Even the difficulty of finding housing for two males is familiar. And there are coming out stories from gay men and lesbians from many cultures in which family—especially mothers and sisters, the only family the adult male couple here has—accept not only their homosexuality but their specific choice of a partner. “There is no greater joy for homosexuals than finding acceptance from their parents,” Yanase claims.

For me, Yanase’s account of moving into the house of Ito and Ito’s mother is the best part of the book. Mr. Yanase (both frequently refer to the other as “Mr. ___”) was so tied up with inhibitions about doing anything that would disturb Mrs. Ito that he could barely breathe. Each author flagellates himself repeatedly for his in consideration for his partner’s feelings. Perhaps such excesses of politeness and consideration is the most Japanese aspect of the book.

That they are grateful to have met each other (n 1986 through personal ads) and appreciate the good qualities in the other bear repeating. I could have done with fewer self-exhortations to be more considerate, however. And “I have never once had anal sex” (97) suggests continued inhibition and makes him (Ito)/them seem even more untypical than their public self-revelations do. (Do normal people write such testimonies? I remember Clyde Kluckhohn wondering about that in regard to the Hopi life history Sun Chief.)

At the time they were writing, a gay group, OCCUR, was suing the City of Tokyo for equal access to a public facility. The case took along time, but finally (in 1997) the court ruled that OCCUR freedom of association is a constitutional right. This case is a backdrop to which both authors frequently refer. I am not sure that I would understand the case if I had not already read the account contained in Queer Japan, published in 1998. Despite its insulting title (imposing “queer” on Japanese not using the word or a cognate or translation), I have to say that I found that book to provide greater insight into gay and lesbian lives in contemporary Japan. Those tell their stories in Queer Japan are generally as or more reticent than Ito and Yanase, so no one is going to learn about the sexual behavior of contemporary gay or lesbian Japanese from either volume.

Among other things, Mr. Ito teaches English. He did not translate himself or his partner into English. If he had, one might be more willing to make allowances for the ubiquity of clichéd phrases. However, there is an Australian translator named Francis Conlan who must be held accountable for perpetrating stilted, cliché-riddled expression. Take for instance a fairly pithy observation: “The more you see yourself as a hero of pathos, the deeper you become enmeshed in that vicious circle.” “Vicious circle” is a cliché, but what is in the text includes an unnecessary and ungrammatical elaboration of “hero of pathos,” so the sentence read: “The more you see yourself as a hero of pathos, the one being wrongly done by, the deeper you become enmeshed in that vicious circle.”

Incidentally, the text of the partner with more formal education is more awkwardly expressed (in English) than is that of his partner, the manual laborer. (They never touch on the seeming difference in class between them.)

Opening the book at random, here is an all-too-typical sentence: “I surrounded myself with people who shared the trait of having the confidence to stand up to the contradictions of society which stared them in the face” (p. 77). The string of prepositional phrases would be bad enough without “which stared them in the face” that is dangling (since it is contradictions rather than society), reifying (animate beings stare, contradictions don’t), and I think ungrammatical (I am insecure about which/that but think “that” would be correct here).

I think that the story/stories of Satoru Ito and Ryuta Yanase are still interesting. It is unfortunate that, 7 and 8 years after publication in Japanese. the story is only cast part-way into English. If not the translator, then some editor should have pared the repetitions and discarded the structure in which many of the same thoughts about the same uneventful “events” are recounted in

• Jottings Notebook

• Self-Analysis Notebook

• Explanation Notebook

• Love Notebook (x2)

• Life Notebook (x2)

• Homosexual Notebook (x2)

(Each of the authors covers his perspective on the same stuff in the last three πnotebooks,” the 1994 book in Japanese.)

I guess this is how the parts were originally written, but not combining the material from the notebooks was a disastrous decision and what makes this book unreadable, even more than the clunky prose in English.

published by Epinions, 19 June 2001

©2001, 2016, Stephen O. Murray