Yulisa Amadu “Pat” Maddy’s novel No Past, No Present, No Future (Heinemann African Writers Series, 1973) begins and ends with Joe Bengoh in the fictional African country of Bauya. “Country body” Joe Bengoh’s drunkard parents’ still blows up, killing both of them and blowing up their home. Joe is taken in by a Catholic boarding school, presumably based on St. Edwards in Maddy’s native Freetown, Sierra Leone, generally regarded now as then as the best high school in the country). There, Joe bonds with two more elite boys who were already close friends, Santigie Bombola, son of a chief, and Ade John, son of a post office official.

There is an early indication that one of the priests, Padre O’Don, finds Joe especially attractive and that at least Ade noticed (“Is he still in love with you,” Ade asks, p. 49). There is no indication that there was sexual contact, and Joe loses his virginity on an outcast village orphan, though he is pushed aside by Ade. That coupling leads to Ade being removed from the school.

Ade gets a job with the railroad, extracting bribes from freight. After Santigie’s graduation (and his father’s death and the selection of an uncle as the new chief), first Santigie, and later Joe join him. In the same order, they go to London for further schooling, Ade in journalism, Santigie in economics, and Joe in acting. The only one who graduates is Ade, who hooks up with a rich, blonde Swede, Bodil, whom he impregnates and is engaged to marry.

Santigie is embittered by failing his exams three times. He lashes out at the English and European colonialism in a public lecture and sets down to living off and mistreating white women.

Joe had a girlfriend, Bola, who turned prostitute and left him for a man with a higher income. Santigie had a girlfriend, Modu, who kept him and promised to wait for him and to send him money in England, but she also moved on after he was gone (and before Joe followed him).

Joe had difficulties with the spinster teachers at the drama school in his first year, but connected with a white boy, Michael, from Wales. Though Joe did better in his second year, he had run up debts and was expelled and was institutionalized in a mental asylum.

After Joe’s release and Santigie’s lecture, at a party in Santigie’s apartment (to which Ade brought Bodil), Ade cuts loose:

You brought your perverse character to the mission. You came there asking for love, cracing affection and attention, you suffering orphan, linsufferable little you. I watched you when you went to the storeroom with Padre. I watched what you were doing, you and Padre. You were both corrupt, you were both sick. I told Santigie… Were you not naked on the sofa with Padre’s hands all over your body? Did you not have your bottom oiled, you screw scum, you dirty depraved dog?… Homosex, battyman, hog boy. (117)

Rather than confirm this knowledge shared back then, Santigie separates the two and expels Ade from the party. Even if known about, homosexual relations are not to be spoken of by Africans.

Joe affirms his homosexuality and is going to rejoin Michael in Rome, where they will teach acting. He goes by way of Copenhagen, having been invited to the wedding of Ade and Bodil. Bodil is like an old friend, and Joe attempts to cushion the pain Ade is causing her, carrying on an affair with another young Danish woman Ade has also impregnated. Ade returns and there is another confrontation with Joe. Joe has accepted his homosexuality and at the end seems the most content of the three now-former friends.

Moreover, Santigie very explicitly accepts his friend and urges him to stick to Michael, who had saved Joe’s life (158) and lauds him for changing for the better: “You forgive and love and understand” (162). Earlier, Santigie had already praised “your sincere feelings for each other” (102).

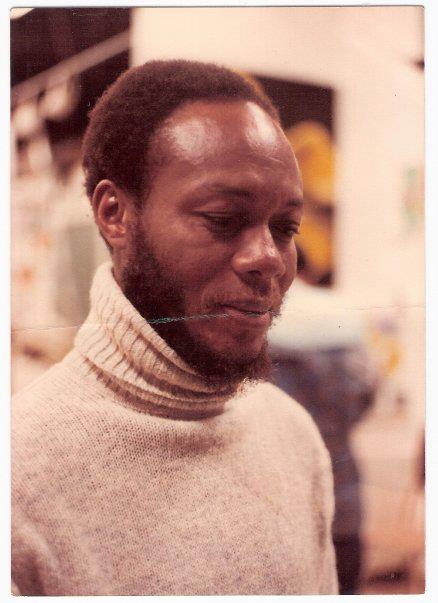

The extended portrait of an African homosexual was startling in a 1973 novel from Africa, perhaps all the more so in that Joe was the character who went to a drama program in the UK, as Maddy (1936-2014) had in 1958. Still, his sexual partners, both in Africa and in the UK (the padre, a young Frenchman, and Michael) are not African, so the book is equivocal a representation of African homosexuality.* It is only after leaving Bauya that Joe affirms that he is a “homosexual” (also “I am a pervert” (164)). Joe does affirm a homosexual identity, having had passionate heterosexual experiences, and his remaining friend from school, however embittered by his own experiences in England as he is, accepts Joe and his homosexual relationship.

*It is not certain that the priest and Joe had sex, but before leaving Bauya, Joe had a relationship with a French boy. In contrast, in Yambo Ouologuem’s (1971) Bound to Violence, Raymond Kassoumi (a student from a fictional French colony of Nakem) is picked up by a Frenchman, Lambert having had no previous consciousness of homosexual desire, though what follows is quite a tender mutually satisfying relationship, unlike heterosexual relations in Ouologuem’s novel. Kassoumi tells Raymond he loves him (158). It is Raymond’s mother arranging a marriage that splits the two after eighteen months of bliss.

© 10 July 2018, Stephen O. Murray