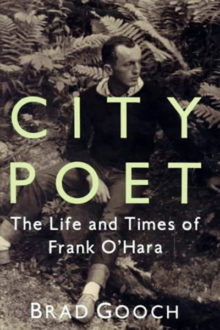

City Poet: The Life and TimeReviews of Frank O’Hara

City Poet: The Life and TimeReviews of Frank O’Hara

by Brad Gooch

Published by Knopf

Published June 8, 1993

History (biography)

532 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com • WorldCat

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

November 16, 2017

Irish-American, Harvard-educated, Navy veteran Frank O’Hara (1926–66) was so stewed all the time that his penis, on display in multiple paintings, was probably just decorative.

He seems to have eaten his heart out over a succession of straight men—preferably painters—who were not interested in being serviced by him. I can’t decide if this is sad or merely pathetic. I guess it can be both. He claimed that it was better to love than to be loved, but briefly reveled when there was some overlap.

I am not particularly impressed by his prosaic poetry (or his poetic effusions about artists he liked and/or whose work he was promoting). He frequently remarked that queens didn’t like him (Warhol tried) while straight painters did. (Or at least they liked the promotions of their work he did at MOMA and in Art News…)

In his exhausting biography, City Poet: The Life and Times of Frank O’Hara (1993), Brad Gooch notes the view espoused by Virgil Thompson that what O’Hara wrote about art served to secure the investment of MOMA collectors (not just the MOMA collection, but those of its trustees), i.e., that there was a clear conflict of interest in O’Hara’s writings about the artists of his times.

I don’t like drunks and doubt I would have been charmed by O’Hara, as so many in that heavy-drinking era were. He seems to have been quite a nasty drunk, becoming more and more vicious as he got drunker and drunker, which he did every day starting from when he woke up. That he functioned as a bureaucrat, arranging many traveling exhibitions, is sort of amazing, and for all his frenetic socializing, he clearly was lonely and unhappy. Much of that came from his being in love with a succession of men who were not emotionally or sexually available to him (Larry Rivers, Bill Berkson, LeRoi Jones, Jan Cremer, and many others with relationships of shorter duration with narcissistic younger men for the most part), though he had a few years with dancer Vincent Warren, before Warren’s career relocated him to Montréal.

I don’t understand how someone whose poetry was mostly “I did this, I did that” could have inspiration dry up, but Gooch’s biography makes it clear that O’Hara had pretty much stopped writing what he and others regarded as poetry in the last years:

During the two years with Vincent Warren, he had written a hundred poems. During the two years form 1961 to 1963 he wrote about fifty—most of them his share of poetic volleys with Bill Berkson. In 1964 he wrote fourteen poems. In 1965, two. In 1966, one. His muse had deserted him.

O’Hara was burned out as a poet, though still functioning as a MOMA bureaucrat, but his death seems less tragic knowing how he living under the influence of alcohol and without love before he was killed.

With a less-damaged liver, he probably would have survived being struck by a dune buggy in the middle of the night on a Fire Island beach. It’s unclear whether the driver, a local, was negligent and protected by the police or whether O’Hara stepped in his path. He struggled to live in the hospital, for sure.

Gooch shows others behaving badly, too, notably Beat writers Gregory Corso and Jack Kerouac. Those who come across as behaving well include painter Willem de Koonig, dancer/amour Vincent Warren, long-suffering roommate Joe LeSeur, and Beat leader Allen Ginsberg.

Brad Gooch seems to have interviewed everyone still alive in the late 1980s who had interacted with O’Hara. There is a tsunami of names, few of them likely to be known even to those with some knowledge of the New York poetry, painting, and sculpture scenes linked together by O’Hara in the 1950s and early ’60s. Explaining who all these people were would make Gooch’s long book (531 pages) even longer and less readable. As it is, Gooch does not analyze O’Hara’s poems and plays, though he quotes many snippets that are laid out like verse.

Brad Gooch seems to have interviewed everyone still alive in the late 1980s who had interacted with O’Hara. There is a tsunami of names, few of them likely to be known even to those with some knowledge of the New York poetry, painting, and sculpture scenes linked together by O’Hara in the 1950s and early ’60s. Explaining who all these people were would make Gooch’s long book (531 pages) even longer and less readable. As it is, Gooch does not analyze O’Hara’s poems and plays, though he quotes many snippets that are laid out like verse.

Gooch does not try to convince readers that O’Hara’s writing was good, and he did not convince me. There is, however, no doubt that O’Hara was a central figure in New York avant-garde networks and the Cold War (the CIA-backed) U.S. art export initiatives, especially abstract expressionist work. That an amateur enthusiast (not to mention drunkard) could occupy so central a position, including the formal one at MOMA, is surprising, and Gooch manages to track whom O’Hara was promoting, whom he was mooning over when. (There is less overlap between the two than one might expect; O’Hara was sensitive to accusations of favoritism in selecting work for traveling shows.)

There is some amusement (schaudenfreude) in watching the avant garde became “old news,” supplanted by the not-at-all-obscure Pop artists. For all the influence of modern jazz and abstract expressionism, O’Hara’s writing was more than a little Pop, so it was not “outmoded” before his death.

©2017, Stephen O. Murray