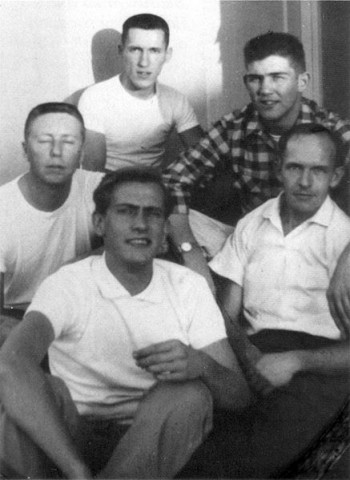

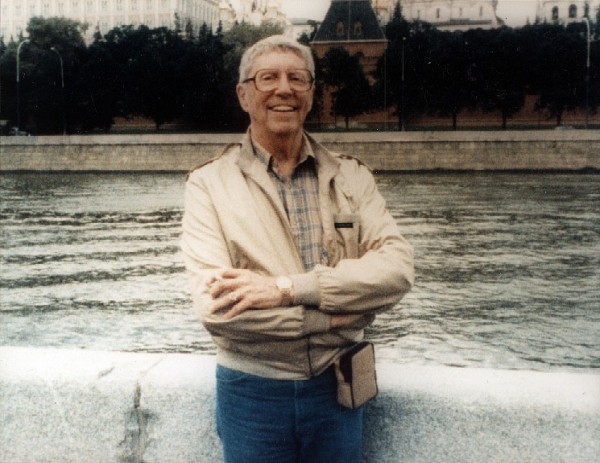

Charles Dennison “Chuck” Rowland

Charles Dennison “Chuck” Rowland

Profile by David Hughes

Posted June 15, 2009

Chuck Rowland was a founding member of the Mattachine Society. He was active with ONE Inc. and founded the short-lived Church of One Brotherhood. Upon retiring from twenty years of teaching in 1982, Rowland founded Celebration Theatre in Los Angeles.

Early Life

Chuck Rowland was born in 1917 and grew up in tiny Gary, South Dakota. He recognized he was homosexual at an early age, and after reading a sympathetic series of articles in a pulp magazine, concluded that, if millions like him existed, they could be mobilized. At the University of Minnesota in the late 1930s, he was active on campus in support of the loyalists of Spain and other causes. While in grad school during 1939–40 he returned to Gary as a substitute for the spring term. On a weekend visit to Minneapolis, he met Bob Hull, a U of M undergraduate. The two had a brief romance, lived together, and became lifelong friends.

Party Time

In 1942, Rowland was drafted into the army. “Frankly, I had a ball,” he told archivist Jean-Nickolaus Tretter, after acknowledging the difficulties others faced. (Due to a severe injury, he stayed stateside during the war.) While enlisted, Rowland became a charter member of the American Veterans Committee, a liberal alternative to the American Legion. After discharge in March 1946, he showed his talent as an AVC organizer, but his active support for veterans’ bonus legislation, which the group disparaged as “handouts,” led to his being “canned” by the AVC by 1947.

While in the AVC, Rowland noted that those he knew to be Communists were some of AVC’s best organizers. “I was just carried along with this feeling of liberalism and the horror of the [anti-Communist] reaction that was setting in,” he told Tretter, “and my feeling was that we had to move farther and farther to the left, as a result of which I got into the Communist Party.” Rowland returned to Minneapolis and headed the CP’s Midwest youth division.[1]Throughout this profile, the term youth should be understood as Rowland probably meant it: young adults, college age and older. (His value as an organizer trumped any chance of being expelled under the party’s unwritten anti-gay policy.) Rowland recruited Hull into the party, and the two contemplated Rowland’s childhood dream of organizing homosexuals.

The devastating 1948 defeat of Progressive Party presidential candidate Henry Wallace, for whom Rowland campaigned, coupled with a personal desire to “start a new life,” caused him to quit the CP and move to Los Angeles, followed by Hull. There, at a labor school, the two met a teacher, Harry Hay, who also had done some thinking about a homosexual organization.

The Mattachine

Harry Hay was developing a blueprint for a homophile support group, but before he could show it to them, Rowland and Hull moved to Mexico in the summer of 1950, intending to relocate permanently to avoid anti-Communist witch-hunts. They returned by fall, however, and received Hay’s completed prospectus, which they eagerly shared with Hull’s new boyfriend, Dale Jennings. The three met with Hay and his lover Rudi Gernreich on Armistice Day 1950, and eventually formed the (necessarily) secretive Mattachine Society and its public nonprofit, Mattachine Foundation.

Hay conceived of homosexuals as a cultural minority, an idea Rowland embraced, but Jennings and others argued that such a notion disregarded crucial differences between gay individuals. Nevertheless, the “minority” (and a Foundation ad-hoc committee) rallied to Jennings’s aid in June 1952 as he successfully defended a “vag-lewd” charge.

Following the victory, the Mattachine achieved tremendous growth, but with some rumbling in the ranks: members wanted transparency and democracy. Thus a constitutional convention was scheduled, for April 1953, but what the founders intended as a conciliatory venture erupted into a dramatic clash of conservative and progressive factions—reflected in a funhouse mirror.

The Old Guard was epitomized by Harry Hay, the brainy leftist who defended the cultural minority model and the cell-like structure that had insulated and protected the individual Society members (under the founders’ guiding hand, via the Foundation). The oppositional Young Turks included Hal Call, a patriotic war vet who, unlike Rowland, had actually seen action. Call and his allies’ aims were modest: “to see the discrimination and ignorance about homosexuality eliminated and then disband,” as Call told his biographer James T. Sears. They were infuriated that, in the event of an official probe, the Mattachine’s Red roots and secrecy might lead to its downfall.

Call, a San Franciscan, actually was a newcomer to the group, but nevertheless he confidently compared his abilities as a doer (in business as well as the military) with those of Harry Hay, whom he considered to be learned but useless to the real needs of homosexuals. Call aligned himself with like-minded Angelinos who craved transparency, favored integration over subculture, and aimed to purge the organization of Communist elements. This north–south alliance organized quickly and brashly proposed its own constitution, based on a hierarchical framework.

Somewhere in the middle was Rowland, who had crafted his own alliances with Bay Area Mattachinos of a leftist slant, while also advocating more democracy. As Hay reluctantly stood by, Rowland and the other founders drafted a constitution of autonomous clubs, governed by committees of correspondence and an annual convention. But Rowland held fast to the cultural minority model as an unintended fact of life, created as it was by society’s exclusion of homosexuals. “Let us accept it, then,” he declared in the convention’s first address, “and move forward to the outermost boundaries of culture.”

The speech, liberally peppered with such rhetoric, allowed Hal Call to easily peg Rowland as a Red.

After a six-week interim and more debate, the final draft dashed any move toward decentralization. And it effectively removed a remodeled Mattachine Society from its Foundation, the latter now branded as being activist, visionary, and obsolete. Indeed, the founders voted to dissolve the Foundation.

Rowland remained active in the new Society, in a chapter that intended to take on legal cases, but the effort was conveniently vetoed when the group’s new attorney advised that “the very existence of a Legal Chapter, if publicized to society at large, would intimidate and anger heterosexual society.” (Such was the logic embraced by the aboveground Mattachine.)

At the next convention, in November, not only were Rowland’s credentials successfully challenged, but the new leaders capitalized on his marginalization by ramping up the Red-baiting. That proved largely unsuccessful, but did result in an altered preamble that removed Harry Hay’s “cultural minority” phrasing once and for all.

ONE and One Brotherhood

Heartbroken by the turn of events, Rowland immersed himself in ONE Inc., writing for its magazine and directing its social services division.

In 1954 he proposed that ONE open a guidance center staffed with gay counselors to mentor the waifs who found themselves alone in a new city. The project foundered, but Rowland nevertheless reported to ONE that in 1955 his division provided job placement and/or vocational counseling for nearly 100 people. (The year before—outside ONE’s umbrella—Rowland had organized The Crusaders, a gay youth group that met at the First Universalist Church.)

In January 1956, tasked by ONE to develop a social-services response to requests the group received for religious counseling, Rowland prepared a report outlining six options. While ONE’s board sat on the report, Rowland studied the options with the group’s promotions committee, which met at his house. The result of those semi-private explorations was the Church of One Brotherhood—Option #5 on his original list—the name lifted from ONE’s slogan, “A mystic bond of brotherhood makes all men one” (Thomas Carlyle).

ONE notified Rowland February 21 of the board’s motion to sponsor “religious group-therapy meetings” via its social services arm, but by that time Rowland’s church was three weeks old, and he, naturally, declined to spearhead the project, although he felt his church could “complement” ONE’s work.

His audacity outraged the board, which felt that he’d not only flouted its leadership, but that his project had pirated development that ONE considered proprietary. On March 1, Rowland received a letter from ONE accepting his resignation—one he hadn’t proffered.

ONE’s Dorr Legg recalled to author Paul D. Cain that Rowland—tainted by his leftist roots—saw the church as a strategy towards respectability. Kepner embellished: Rowland had conceived of the church as a First Amendment “shield” to organize behind in the event of a crackdown on undesirables.

(Rowland was, in fact, at that moment being investigated by the FBI for something he’d written in ONE Magazine in November of 1955.)

Rowland’s small church began its short life with an ambitious list of more than 50 committees and social services. In what turned out to be a last gasp, it launched a sort of Crusaders v.2, an “entirely non-liturgical” “youth affiliate” for social activists, dubbed The Prometheans.

By early 1958, for reasons that are obscure, the church folded. Sometime later Rowland suffered a nervous breakdown. Legg told Cain how Dr. Evelyn Hooker, who’d included Rowland in her pioneering 1954 study of gay men, had said bluntly after seeing him: “He’s gone.”

Exile on Main St.

Rowland’s mental health returned, and in January 1960 he appeared at a ONE educational conference: on a panel titled “The Homosexual in the Community” and in a staged reading of James (Barr) Fugaté’s Game of Fools.

The next two years saw Rowland involved in a possible FBI blacklisting (as Red and gay), a failed business partnership, a dependence on intoxicants, mounting debt, and eviction. Finally, following the tragic suicide of his friend Bob Hull in May of 1962, Rowland returned to the Midwest. That summer he was hired as a credentialed high school teacher in Iowa. Obtaining his master’s degree in 1967, he chaired the theater arts department at a Minnesota college.

Upon retiring in 1982, Rowland returned to Los Angeles from his “exile,” as he put it, while admitting to “some worthy accomplishments” and meaningful relationships.

In late 1982, with Jim Kepner and ex-Mattachino Martin Block, Rowland founded Celebration Theatre, billed as “the only theatre in Los Angeles dedicated exclusively to productions of gay and lesbian plays.” Kepner hosted its debut in the late spring of 1983, in his National Gay Archives.

Celebration

Rowland fondly recalled that first production, written by two members of London’s Gay Sweatshop theatre collective.

As Time Goes By was set in 1896 after the trial of Oscar Wilde, 1930s Berlin, and 1969 when gay liberation achieved its very public face. The show was the last for its director (and former Mattachino) Philip Cary Jones, who died just after it closed. He and the players received higher marks than the work itself, which critics found trite, didactic, and verbose. The company went on, however, to win numerous awards, and its productions saw life in other venues.

Rowland conceived of Celebration as a “community theatre of talented amateurs and volunteer professionals,” but as noted by John Callahan, who assumed direction of Celebration in 1990, such a notion was impossible in Hollywood, where talented amateurs were scarce, and the label itself would be seen as a contradiction in terms. Despite Rowland’s misgivings, Celebration made a “Showcase code” agreement with Actors’ Equity allowing union members to work on its small productions.

Celebration’s thirty-first production, in September 1990, was Jim Pfanner’s Small Town Confidential, loosely based on the 1955 incident in Boise involving three men and teenage boys, which threw the town into a panic (much like L.A.’s McMartin preschool case thirty years later). By this time, however, Chuck Rowland was in a hospice situation—an exile once more.

Having been hospitalized in March with prostate cancer that proved to be terminal, Rowland “moved to Duluth where a former student fixed up a handsome apartment overlooking the lake,” according to a Kepner-penned obituary. “He spent five happy months among students and relatives….”

Chuck Rowland died December 27, 1990.

Aside from his theatre work, Rowland spoke publicly about his movement activities. He is featured in numerous books, including Stuart Timmons’s The Trouble with Harry Hay: Founder of the Modern Gay Movement and Allan Bérubé’s Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War Two, as well as Eric Marcus’s Making History: The Struggle for Gay and Lesbian Equal Rights, 1945–1990: An Oral History, James T. Sears’s Behind the Mask of the Mattachine: The Hal Call Chronicles and the Early Movement for Homosexual Emancipation, and John D’Emilio’s classic “Dreams Deferred” series for the Toronto monthly Body Politic (included in his collection, Making Trouble).

Rowland appears in the documentary films Before Stonewall and Changing Our Minds: The Story of Dr. Evelyn Hooker and is depicted in Jon Maran’s stage play, The Temperamentals.

Celebration Theatre continues to service the community.

In addition to the authors listed above, I thank ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives, Jean-Nickolaus Tretter, John Callahan, C. Todd White, Paul D. Cain, the St. Louis Park Historical Society, and Andrea Carney for contributing valuable information to this profile.

Text by David Hughes. © 2009–2011 David Hughes. All rights reserved.