Four Trips to Cherry Grove

Four Trips to Cherry Grove

Part 3: Trip 4

by Leo MacAlbert

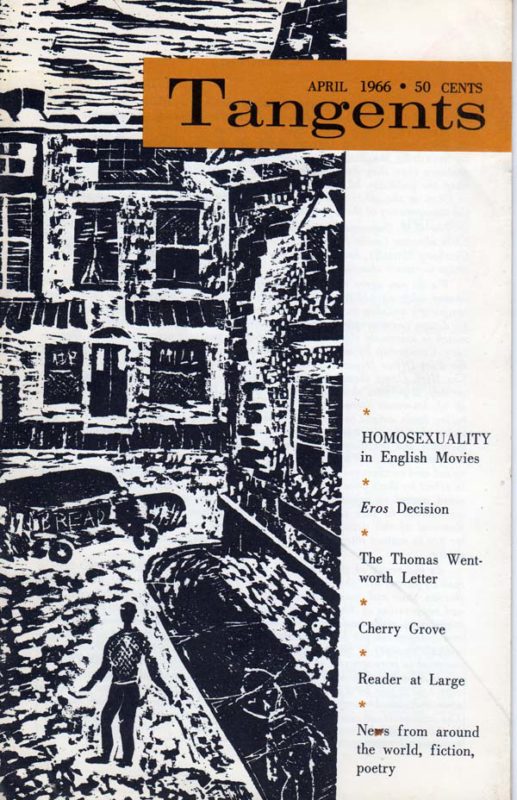

Tangents Vol. 1 No. 7

April 1966

Originally printed in the April 1966 issue of Tangents

pp. 17–21

TRIP 4

Rey was still in Atlantic City. He would be back Sunday night. He had written, asking me to call him then.

Meanwhile I would be going to the Island alone.

Now I sat looking out the train window, watching the tinctures of evening enter the sky. It was almost like dying peacefully. I thought of Colette’s “A Sick Boy’s Winter.”

By the railside, we passed heaps of scrap. There seemed to he so much scrap.

The train was quite full, full of normal people, mostly older men, wearing wedding bands, reading the World-Telegram. The one beside me was doing the crossword puzzle. The straight world—their restfulness. That was the first thing you noticed about gay kids—their restlessness, always turning their heads to look at something….

After parking my things at the Monster—smiling, thinking of my Spanish Rey calling it the Dragon—I walked over to the house of Andre. He had invited me for the weekend. Why hadn’t I accepted? I wanted to save money, wanted to have the business of eating, etc., taken from my hands. Andre had offered all this. Why didn’t I accept? I kept asking myself this only until I reached Andre’s house.

He was glad, but not overjoyed to see me. He did not insist that I stay at the house. They had just finished supper. He did offer me food. I was amazed to see how he and all his friends kept the house so neat. The food was put away, the dishes cleaned by them all together. It reminded me of all the animals helping Snow White with her housework.

The two friends Andre was closest to looked very much alike—dark, dark-haired, cross-eyed, one Italian, the other Spanish. There was another boy there, handsomest of all, wearing a string across his forehead like the Greek fillet.

They wanted to go over to the hotel where the dancing was. I must go with them. Would I shave? I went inside to shave, and while I was shaving they laughed at some remark. I didn’t hear the remark but only the laughter. Still, it cut me, that cruel, hard, fairy laughter—something I had never heard in the World Outside. We are often foolish when we think ourselves clever; in that moment of ease and laughter Andre had lost a night of affection from me.

“Do you have shorts?” Andre asked when I came out. “We’re all wearing shorts.’’’

I put on my shorts.

Before we left for the hotel, the handsome boy, the one Andre and his friends did not like, removed the fillet from his forehead. It turned out to be part of a hairnet he was wearing.

Though none of the group danced, except me, we left only at closing time. Andre, as I knew would happen, did not take me back to his place but asked me if we could go to mine. That way his friends, who would otherwise have to sleep on the livingroom couch, could have his room and privacy.

I agreed.

We walked to my place through the slight drizzle that had begun. I had to take a shower. The stairs to the second story where the shower was, were outside. I, barefoot, drunk, nearly slipped. It was a funny new sensation—this taking a shower in the rain.

The little bed downstairs was hard. The sex was bad. I like the affection and company as much as the next man, but I cannot start answering questions at three or four in the morning, and Andre kept asking if he was making me happy.

When it came time to get up, he was less concerned. In fact, he announced that his ami would be back and he would be having breakfast with him and could not ask me. I said only that I would like to pick up my shaving things from his place. We walked there together in the rain.

Walking back from Andre’s—it was wonderful being alone again—I met Mr. X, who was more pleasant than he had ever been before. Apparently he is one of those people who flower in foul weather. He couldn’t go out in his boat today. He is one of the boat people whose lives revolve around their little craft, getting them and keeping them. In addition, he had several pet snakes. He was also fond of symphony concerts. We stood there talking in the rain, like two plants being watered….

Walking back from Andre’s—it was wonderful being alone again—I met Mr. X, who was more pleasant than he had ever been before. Apparently he is one of those people who flower in foul weather. He couldn’t go out in his boat today. He is one of the boat people whose lives revolve around their little craft, getting them and keeping them. In addition, he had several pet snakes. He was also fond of symphony concerts. We stood there talking in the rain, like two plants being watered….

I ate supper alone at the Sea Shack.

I arrived too early. The staff was eating.

“Couldn’t you serve me something now?” I asked.

“Honey,” the waiter said, “you could make mad love to me for an hour and I wouldn’t give you an appetizer.”

Nu. I waited till seven.

I had a small table, my back against the wall. To my left sat a middle-aged sugar daddy with his ward, an under-aged, wide-eyed Cuban kid, skin shiny with newness.

Sugar Daddy: “That man we just met at the party is a millionaire. If you played your cards right, you might get him.”

The little Cuban boy put a big shrimp into his mouth. “He’s not a millionaire,” he said. “I asked him after you told me that, and he said he wasn’t.

“Oh,” said the sugar daddy, “is that why you didn’t go with him. But if you did find a millionaire, or you were sure that he was, you’d get him, wouldn’t you?”

“No,” said the Cuban boy, and put another big shrimp into his mouth, “I would stay with you.”

“Oh,” said the sugar daddy. “You’re just saying that.”

This conversation repeated itself and repeated itself.

I ate, staring in front of me, not at the people but at the hours ahead, somehow more vacant than in New York City. The New York streets—odd I’d never been grateful for it before—were different, offered a real diversion. Here there were ten short walks, each lined with 20 houses. I had already become overfamiliar with them, even finding myself irritated at the one or two whose owners let their front shrubbery grow over the walk, obstructing traffic. In New York you were grateful for the one or two buildings that positively didn’t offend.

That night Cecil, a Negro boy who had once worked in my office and who now was a professional dancer—and his friend Ebenezer—took me to the drag show. It was held in a big barn-like building with benches for seats, all on one level. Our seats were on the back bench. And when we climbed up on the bench to see better, a cute blond kid in front of me stood up. His head was at my belt level. I rested a hand on his head, like Columbus at the helm, surveying the New World.

Lila Leeds was Mistress of Ceremonies. Blond wig. Blue eyes. The program notes gave no other names, and the only performer I recognized was little Ralphie. Lila Leeds was covered with a sequined net. The lights reflected from it spun across the walls and ceiling. It was one of the best costumes I’d ever seen.

The opening was the prelude from Carousel, with little Ralphie in the center as an Egyptian kootch dancer, very attractive in a black wig, his brown skin oiled and smooth. But the fact that he hadn’t shaved under his arms kind of loused up the grand bouree he couldn’t resist making when the applause started and time came for his exit.

The best skit of the night was a take-off in two scenes of a Victor Herbert-type musical, combining the plots of Little Mary Sunshine and Rose Marie. Needless to say, the Indian chief was a queen, the lost white girl brought up as an Indian had a Yiddish accent, and so on.

There were imitations of Judy Garland dressed as a ragamuffin, Tallulah Bankhead on Hitchcock’s Raft—“I’m fishing; everyone knows Tallulah likes fish”—and finally, of Carol Channing, who is apparently Man of the Year at the Grove.

I watched, conscious of the division between myself and the rest of the watchers. The years spent in college, not watching TV, and the years afterward, still not watching it, then not going to Broadway shows—had separated me from the others. I found this world frightening, threatening, as if I’d stepped into an Arab slave market. The absolute whorishness of it, the faces and the voices coming at one: Look-at-me-look-at-me-love-me- yes-yes-yes-I’m-so-happy-and-we’re-going-to-be-so-happy-together-yes-take-me-me-me-me!

I picked up the blond boy. I thought I had picked him up. His name was Ralph. Ralph Number Two. But just at the exit he said, “Oh, I forgot my program. Excuse me,” and went back inside.

I waited. Time passed. The crowd was gone and a long line began to form outside for the midnight show. No Ralph Number Two. I caught up with Cecil and Ebenezer and went with them to the dance hall. No Ralph Number Two there, either. I left a note for him with Cecil and began roaming the walks, calling, “Ralph, Ralph,” as if for a lost cat.

Andre came over to me and asked if he could sleep with me that night. “Sure,” I told him, still looking for the second Ralph.

Suddenly I saw him. dancing on the floor.

“Excuse me,” I said to Andre.

I went and got Ralph Number Two and walked out of the Hotel with him. “I was looking for you,” I said.

“We can’t sleep at my place,” he said. “I just have a couch in the livingroom of my friends house.”

“I have a private room at the Monster,” I said. “But I’m seeing someone else tonight. Maybe some other time.”

However, we came to the Monster and to my room. On the wall was a map of Rome with all the monuments sketched in miniature. We began kissing. He began snorting. Zip! He pulled down his pants, gave me an appealing, dying-dog look, rolled his eyes backwards till they searched the botanical prints on the window shade. I didn’t react. I did react, but inwardly, silently. I didn’t like his dick. He looked at me again, gave a slight snort.

“We better get back to the dance,” I said.

He zipped up sulkily.

“Maybe I can see you some other time,” I said.

“No,” he said. “I can see we are not going to get along.” He is German, an immigrant, a hair-dresser out on Long Island.

Back at the dance I met Andre. “Shall we go?” I said.

He made a face. “Let’s call it off.” “Okay,” I said.

I went out for a walk. Oddly enough the boardwalks were almost completely deserted. It was very peaceful.

Someone walked up to me. It was Andre.

“You shouldn’t walk out here at night,” he said, “The police will pick you up.”

“Let them,” I said. “I’m free to walk, look at the stars, breathe the night air.”

He went off. Probably cruising. Bad, sad world.

I walked some more, finally back to my room.

On the wall of the toilet—Shiva dancing. Indian tourist poster.

On Sunday, women’s voices woke me.

First Woman: “He called me a lousy dyke and a souse.”

Second Woman: “Well, that’s just about par for the course.”

First Woman: “And he told me to go to hell.”

Second Woman: “Well, that’s just about par for the course.”

First Woman: “He said I was a lousy dyke, which you know isn’t so.”

Second Woman: “Well, that’s just about par for the course.”

First Woman: “I got a lovely lamp from him. He asked for ten and I said five and he called me a dirty bitch.”

Second Woman: “Well, that’s just about par for the course.”

First Woman: “I would have had to pay much more in the city.”

The talk at Andre’s that afternoon was, in its way, no different. It went like this:

“You know,” from the cross-eyed Italian boy, “I was walking out on the beach yesterday and passed a beautiful boy. He was a real glamour-puss. But I saw that he hadn’t taken the trouble to roll his socks. They were just hanging. And you know, all his powers of attraction were lost.”

He nodded at the others.

I looked down at my socks, which were not rolled, and at the socks of all the others, which were.

I rolled my socks.

“I don’t know,” I said, “I never have thoughts like those. My thoughts if anything, would be what the boy would be like without his socks.”

“No,” the Venezuelan shook his head. “It’s terrible to see someone with messy socks.”

“You should comb your hair,” one of them told me.

“No,” another said. “That’s his style.”

I hadn’t even brought a comb. To me, the sight of a boy combing his hair, like a girl putting on lipstick, was, if anything, a little offensive.

There was a moment of silence.

“I hate going home,” said Andre. “As soon as I go home, I want to go out again.”

“Not I,” I said. “I like being alone. I like to read and write—“ But here I broke off because the person I was describing seemed to me to have ceased to exist. When was the last time I had read a book—I mean, to its end?

I stared in front of me.

Was this the New Life I was to enter, to sit in this clean, well-decorated room, listening to endless, diffuse chatter about socks?

Andre reminded me my boat would be leaving.

He walked with me to the dock.

On the train back to Manhattan, two girls sat in front of me.

“The people on this train,” one said to the conductor, “look awful funny.”

“That’s the weekend crowd,” he said. “They go with their poodles to Sayville.”

He meant whippets.

I got off at Penn Station, restless and adrift as I always am on Sunday afternoons, coming back to New York. I phoned Rey’s apartment from a pay station. No answer. He was not yet back from Atlantic City.

I began to walk to 42nd Street.

A small calico kitten, its eyes full of mistrust, followed me a half block, retreated behind a carton in a shop doorway when I turned around.

“What is it?” I said. “What it is?” The kitten’s head reappeared around the corner of the carton, its eyes still mistrustful.

Take me, was the message, take me into the Great Boat of Life.

“No,” I told the kitten, “Rey is coming hack from Atlantic City No time. No time.”

I walked on.

At 42nd Street I bought a copy of “New Orleans,” the record that had become the favorite dance this last weekend. Even holding the record in my hand as I walked uptown, I could recreate its rhythms, the special steps taken up—the young, thin Negro boy leading the group like fishes into the new steps. Strange to see, strange to think about—this primitive group culture, like children, savages! The strange, needful monotony, the repetition of the music!

I went into Bickford’s a t 50th Street, ordered a hamburger well done with a slice of raw onion.

I went to the phone booth and called Rey’s apartment.

He was in.

“ I just came back,” I said. I’m at 50th Street. Do you want me to go to my house and rest and see you later, or shall I come down now?

“Come now,” said Rey.

©1966, 2016 by The Tangent Group. All rights reserved.