Harold Leland “Hal” Call

Harold Leland “Hal” Call

Sept. 20, 1917–Dec. 18, 2000

Interview by Paul D. Cain

Edited by David Hughes

This interview with Hal Call was conducted by Paul D. Cain in San Francisco in May 1994 and posted here on May 29, 2017

Introduction

From Paul D. Cain’s prefatory remarks regarding this interview:

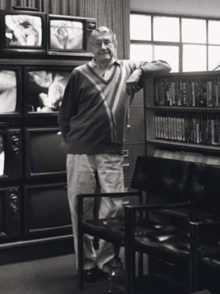

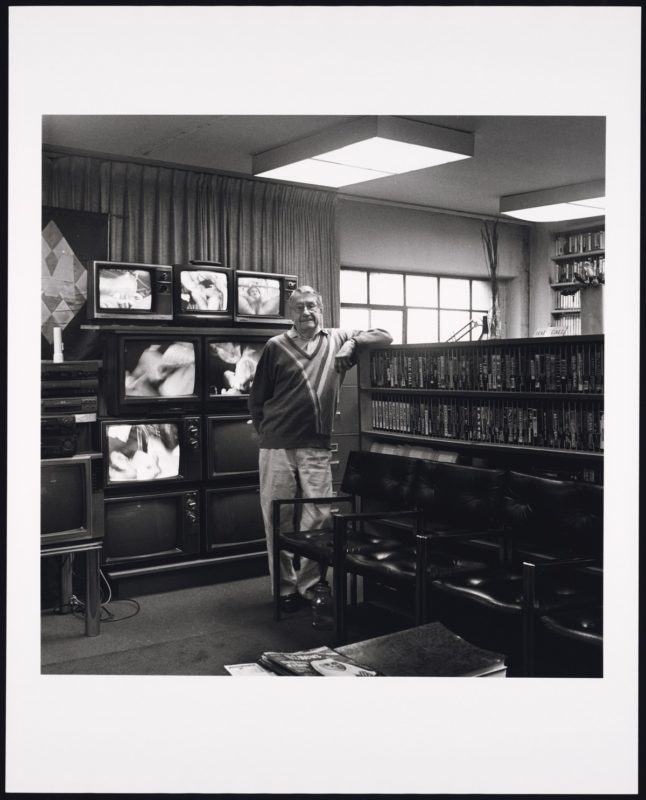

I met with Hal at his place of business, San Francisco’s Circle J Cinema, in May 1994. It was the most unusual setting among my interviews; while Call proudly displayed the original Mattachine banner on the wall of his office, ten video screens simultaneously displayed hard-core male erotica. (It took all my concentration to focus on Hal!)

On Don Lucas

[Start of Tape 1, Side A]

I’ve got all sorts of things to talk about with you. What I’d like to do first, the pattern I’ve been using with people so far, is to go ahead and start talking about some of the people, and some of your first thoughts, recollections, about them, what kind of comes to mind, and then we’ll see kind of where it goes.

To begin with, I’d like to start with somebody I know you were fairly close to, Don Lucas.

Yes. Don and I were business partners for several years. Don’s still alive.

Yes. I’ve written to him, and I know that he got the letter because he signed it, but I haven’t heard anything from him.

Well, he’s in retirement, and he’s a recluse right now. He used to do my annual income taxes, but he’s even quit doing that. And he’s living with his old mother, who is in her upper 90s…

Ah!

And they just don’t go out. And while Don is younger than I am, he is—his health isn’t too good, and he doesn’t do anything. He stays inside all the time. But he’s here, and I can give you his phone number.

Oh, OK. Sure. I’d—yeah, I’d like to touch base with him. I know that a lot of…

Well, Don and I got into the Mattachine together, back in 1953. Right. And Don did the office work, and kept the records of the Mattachine Society at that time, and of the little commercial business…

Pan-Graphic.

Pan-Graphic, that some of us started. Don and I were among the partners in it, and that worked so that ultimately I bought all of them out, including Don. Pan-Graphic Press was organized to print publications for the Mattachine Society, because we wanted to have a printing press, and we wanted a printing press that was not subject to the whim of the newest wave of voting members of the Mattachine Society.

Right.

Who could come in, and move it out, and take the press out, the printing press with them, and move somewhere else with it. So we established that as a commercial enterprise. To serve the gay community, and it’s been doing so since 1954. It’s the oldest gay business established for gay, for gay service in San Francisco.

Right.

On Adonis Bookstore and DSI

This is our 40th anniversary year. All right. Don was with us in all of this, and later we had developed the Adonis Bookstore. Starting roughly in 1967. And we had, there were—I was instrumental in organizing the trial strategy, and getting witnesses, for a male nude obscenity case in Minneapolis then, that Directory Services [Inc.], DSI, back there, that was the case that we won in Federal Court. And that opened the door for the male nude to go through the United States mails. And I—really, that was a pioneer case that opened the floodgates of what’s happened in the field of erotica.

You say that was in the mid-sixties?

1967. In Federal Court, in Minneapolis. I’m the one that really, was essentially the person that won the case for them. I got the witnesses that testified in front of a judge, which was satisfactory with the federal government at the time. They were so certain they were going to win their case against us. And they were absolutely shocked when they found out that the clients, the defendants, were acquitted on all 24 counts of obscenity that the federal government put against them.[1]Records of the DSI trial are in the Jean-Nickolaus Tretter Collection in Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual and Transgender Studies, University of Minnesota; see finding aid.

Right.

Now, that started erotica in the country. We had an Adonis Bookstore going here, at the time. OK.

On Selling an Idea

Let me go back for just a second. I found it interesting, and I read this in Eric Marcus’ book also,[2]Marcus now has a website of podcasts devoted to the oral history interviews he did for his 1992 classic Making History: The Struggle for Gay and Lesbian Equal Rights, 1945–1990 (later titled Making … Continue reading that you wanted a paid staff and tight control of Mattachine when you got hold of it, and didn’t want it to be subject to the whim or the mode of the newest wave of members. After all, isn’t that what you did to Harry Hay and Chuck Rowland, in effect?

Well, in a way. Of course, Harry Hay and Chuck Rowland and those boys, in the Fifth Order of the secret Mattachine Society [Foundation], they had the idea for the Society, but they had not the slightest grasp of public relations, or how to promote something, or how to sell an idea!

Right, right.

They didn’t know how to do it! It was their idea, and I’m the one that developed the sales of it. What little there was done in that period. Because it was such a rough period. It was the era of Joseph McCarthy, Senator McCarthy, and all that government, State Department nonsense, and so on.

No. I long knew that if an organization of that sort—and we were really far out. We had to have a kind of steadfast leadership—yes, and control! So if someone new—a new group, couldn’t come along, you might say, and take the bit in their teeth and run with it in directions that would . . .

Be harmful.

Yeah, that would subject all of us to the worst of our government and society could devise for us.

Right.

So we also knew that this was a full-time thing. And volunteers are wonderful, yes. But you cannot volunteer yourself for eight hours a day, and seven days a week forever!

No. That’s right.

You’ve got to have someplace to have some revenue, and a cash flow of some kind, that will pay the bills of the people working. Now, and another thing about volunteers. New people came into Mattachine all the time. And there were people, really, with trouble, with something within themselves, their own coping and understanding their own sexual identity. And various things like that.

Are we talking pre-1953, or after ’53?

After ’53. Yes. Because we got it, we were instrumental in the Foundation, turning it over to the democratic Society in 1953. We wanted to know who officers were then!

Right, right.

And they all had Communist backgrounds. Every damn one of them! But that wasn’t too bad at that time. Because there were Communist groups on almost every major college campus in the country.

Right.

At that time, we were Russia’s ally in World War II!

Correct. Correct.

OK. But the frenzy, anti-communist frenzy, and the—oh, and the era of Communism, was getting underway in the United States. And the things that developed into the Cold War were originating and taking place then. Anyway, we wanted a staff that would be able to be steadfast, and could be called on to have some knowledge and authority about it, to head up this Mattachine project. And it was not a project that conceived in the beginning to create an entirely new substrata [sic], or a homosexual suborder, in society, as the Foundation was. Harry Hay and his friends, they wanted Mattachine and its people, gay people, to be another sub-group in society. We didn’t feel that way. We wanted to blend into total society, and be assimilated, and accepted by all. And we felt that, by the time everybody knew and understood about the elements of homosexuality, and how widespread it was, and where it came from, and so on—because at that time we knew, we certainly knew it came from Mom and Dad!

OK. But the frenzy, anti-communist frenzy, and the—oh, and the era of Communism, was getting underway in the United States. And the things that developed into the Cold War were originating and taking place then. Anyway, we wanted a staff that would be able to be steadfast, and could be called on to have some knowledge and authority about it, to head up this Mattachine project. And it was not a project that conceived in the beginning to create an entirely new substrata [sic], or a homosexual suborder, in society, as the Foundation was. Harry Hay and his friends, they wanted Mattachine and its people, gay people, to be another sub-group in society. We didn’t feel that way. We wanted to blend into total society, and be assimilated, and accepted by all. And we felt that, by the time everybody knew and understood about the elements of homosexuality, and how widespread it was, and where it came from, and so on—because at that time we knew, we certainly knew it came from Mom and Dad!

[Laughs]

Heterosexuals breed homosexuals.

Right.

But you never hear that. You don’t hear anyone—you hear people wanting to outlaw homosexuals, and outlaw homosexuality. But none of them outlaw fucking, or outlaw having babies, mother and father.

Correct.

And homosexuals are coming from that all the time.

Correct. Correct.

We got in with an idea that had to be sold on a public relations basis, and we had to—we treated our technique mainly as an educational project, and our concept was to eliminate the prejudice and ignorance about homosexuality so that the homosexual in our midst could be assimilated in total society, as a responsible person, simply different in the choice of sex object. That was about the only difference he or she really put forth. And that otherwise, the problems of the homosexual in society, when that was achieved, when that status of acceptance and understanding was achieved, the “problem” of the homosexual would fade away, and there wouldn’t be any, and Mattachine could disband! In fact, when we got started in our creation of the democratic Mattachine Society, in our original aims and purposes, we stated the fact that we ultimately hoped to disband.

MCC [Metropolitan Community Church] was the same way, when they started. That sort of thing. Isn’t it interesting, though—I find it very interesting that forty years after the fact, that same argument, in effect, is still going on.

Right.

Do we create a separate community, or do we integrate ourselves into the larger community?

Well, now, there are those that want the subculture.

Oh, yes.

Oh, yes.

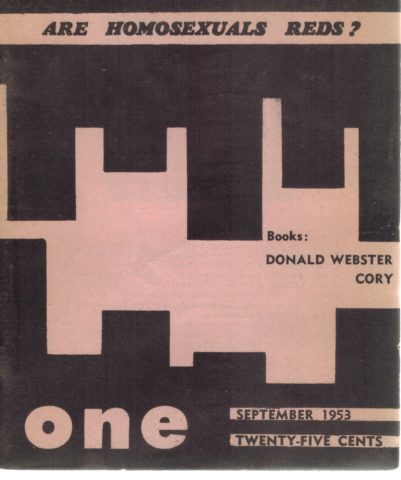

And ONE, Inc., which came out of Mattachine, essentially—the idea for ONE, Inc. was good, to create a magazine that the Mattachine Foundation down there could not [unintelligible] about.

Right.

And Dorr Legg, W. Dorr Legg, one of the founders of ONE, Inc., was at that time the treasurer of the Mattachine Foundation!

Right. I interviewed him a couple of months ago.

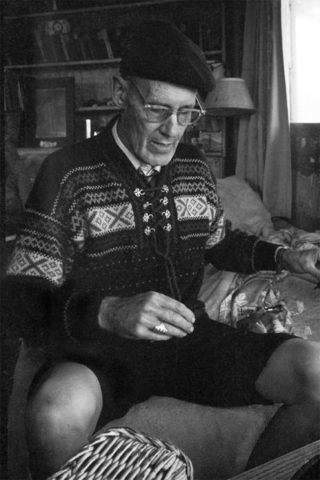

You did. OK. And wonderful Dorr—he’s 90 years old.

Yeah. He’ll be 90 this year. I figured he would be about mid-seventies. And I was very surprised . . .

He is 14 years older than I.

Yeah. Born in nineteen-aught-four, he told me. [Laughs]

He is a marvelous, marvelous man. But he somehow—OK, well, the interview today isn’t about Dorr Legg. But I love Dorr.

That’s all right. We’ll get into that.

On Prescott Townsend

Let me get back to a couple of these people, ’cause we’re gonna do Mattachine in great detail. I just want to hit some other folks first. Did you know a man by the name of Prescott Townsend?

Yes.

What can you tell me about him?

He was from Boston, wasn’t he?

Yes.

Well, he was a gay gentleman who was, he was organization-minded and he was proud, Mattachine Project-minded. He is older than I—he was older than I am. I’m sure he’s probably long-gone.

He is.

But he, he tried to, you might say, plant and develop the Mattachine idea back in New England.

Right.

And he stood up to some derision, and criticism, when it was discovered by someone what he was doing, and what he was about, and who he was. So he took quite a bit of derisive criticism. Prescott was one of the oldest, early, outspoken people. Away from the central core of Mattachine here and on the West Coast.[3]See this profile of Townsend by Mark Krone in Boston Spirit magazine.

Right.

There was a Richard Inman that was in Florida, and there was Frank Kameny in Washington, D.C. that was. And there was . . .

I’m going to see Frank next month.

Uh-huh. Dr. Kameny, an astronomer.

Yes.

Oh, he is a—he is a terror . . .

[Laughs]

And he’s wonderful. He has, is still indefatigable, and active, and he’s been a burr under the tail of the Federal Government, and in the District of Columbia, for 35 or 40 years. [Laughs]

Yeah. I can hardly wait to go see him. I know it will be great. In the packet that you sent back to me, that had all the names that you were kind enough to check off, and you did a better job of that than anybody that I’ve sent it to, thank you very much.

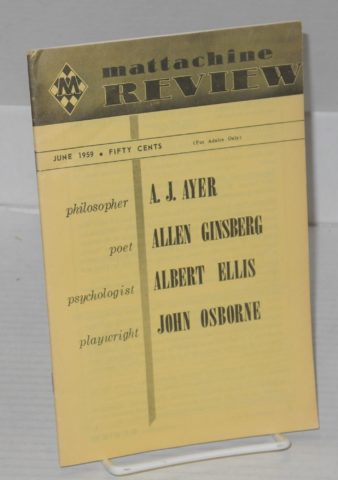

I knew all those—I knew or I met all those I checked off. Even Allen Ginsberg. Ginsberg wrote a poem for our Mattachine Review![4]“The Green Automobile” published in Mattachine Review, Vol. 5, No. 6 (Jun 1959). The poem was collected in Ginsberg’s Reality Sandwiches (1963).

I knew all those—I knew or I met all those I checked off. Even Allen Ginsberg. Ginsberg wrote a poem for our Mattachine Review![4]“The Green Automobile” published in Mattachine Review, Vol. 5, No. 6 (Jun 1959). The poem was collected in Ginsberg’s Reality Sandwiches (1963).

Did he?

Yes. I ought to look it up sometime, it ought to be reprinted.

Sounds great!

On Allies

One of the people you wrote down was Wardell Pomeroy. I did not know he was gay.

He’s not gay.

Oh, he isn’t. OK.

He was Kinsey’s associate.

Right. Right.

Wardell Pomeroy has been working with Ted McIlvenna here, in the—and Ted McIlvenna isn’t gay.

OK. OK.

There’s a number of them in there that are not gay, in your list. I think. Anyway, Wardell became Dean of Faculty for the Institute for the Advanced Study of Human Sexuality here. Which is a project group that grew out of what Ted McIlvenna got started in the late ’60s called the National Sex Forum. And it evolved into this Institute, which is an educational institute, and it issues a doctor’s degree. I have a doctorate in sexology from that Institute. And I’ve been on the faculty of it, and Wardell Pomeroy was the Dean of Faculty at that for a long time. Wardell is very—he’s old and feeble now, and he and his wife have moved back to Bloomington, Indiana.[5]See reprint of Pomeroy’s Los Angeles Times obituary and McIlvenna’s profile, both from San Francisco Chronicle.

Yeah. The book is going to be focusing on the 100 gay and lesbian people who were most influential in the movement. That’s why Evelyn Hooker isn’t on it, and several others. That’s a second book I hope to do, somewhere down the road.

On Alfred Gross

Did you know a Dr. Alfred Gross?

Yes.

In Connecticut?

I knew of him. He wrote some books, and I think he was—wasn’t he critical of us? Of gays, or . . .

He went sort of back and forth.[6]See this (as Cain says, “back and forth” but intriguing) profile of Gross at the LGBT Religious Archives Network.

I heard somewhere or other he was a psychiatrist in Baltimore, or something, whose name I’ve forgotten now, I think it was on your list, who in the beginning of Mattachine’s activity, was it Mattachine Review, he mentioned about the Mattachine Review in one of his books, and said all the people in it are pseudonyms, none of them ever use their right names. And the biggest pseudonym of all is that, probably that Hal Call. Well, my name is Harold Call, and I go by the nickname of Hal.

Right. Right.

I am not a pseudonym. I’ve forgotten that psychiatrist’s name, but he was—well, he was an idiot.

[Laughs] We don’t need to talk about idiots.

We got a lot of crusading behavioral scientists that are steeped into the realm of idiocy. OK. Go ahead.

On José Sarria

How about José Sarria?

Yes, José Sarria I think ought to be in it, as an entertainer.

I talk to him tomorrow.

Yes. And, you know, he worked through the Black Cat days, and he did a lot, spreading the gay word back in the early fifties.

Right. And he ran for Supervisor in ’61.

Yes. And we did the printing for him at Pan-Graphic Press.

Aha!

And he got, I think it was six or nine thousand votes.

Six thousand.

And he was the first one that ever, first gay that we know of that ran for office here.

Right.

Outwardly gay. We were involved in the 1959 mayor’s election here in San Francisco, in which Russell Wolden accused—you know the details of that.

Yeah.

George Christopher and all that. And, of course, Christopher trounced Wolden, and Wolden was ran out of office later in disgrace, and he’s dead now. And gone. Thank God. Oh, José Sarria, yes. You want to mention some more of them. Go ahead.

Yeah. If there’s anything else about José you want to say. I mean, anything else I might . . .

Well, José has been a good crusader. And a lot of people pay attention to him, because José has done his crusading from the entertainment stage. Now, he’s in drag much of the time, but everybody that loves him, they accept the fact that he’s in drag. And he’s not—he may be treated, and referred to with female pronouns and that, but José is very much a well-respected crusading gay men here. And long has been.[7]Editor’s Note: José Sarria is included in Martin Aston’s survey of queer music Breaking Down the Walls of Heartache, which I reviewed.

Absolutely.

On the Mattachine Takeover

Let’s talk a little bit about Ken Burns, Marilyn Rieger, David Finn. Sort of the takeover. What you can tell me about them that I might not have otherwise.

Well, we have been—Mattachine has been, I think, unjustly criticized about this thing that happened at our convention in Los Angeles in—I don’t know. Was it the first convention or the second one, in 1953? Either April or May, 1953. About—well, David Finn was the one that actually got up and made the threatening, the threat to turn certain names over to the FBI. Well, there was no need to; the FBI had ’em already anyway. [Laughs]

Do you think, Hal, that that was really a serious threat?

No!

He would not . . .

We were not—we were not really doing that. We opposed, we opposed what was going on. It was the secrecy and the possible Communist backgrounds that the people were Harry Hay and his five or six or seven friends that comprised the Fifth Order of the Mattachine Foundation. And they gave the Mattachine Foundation to a democratic Mattachine Society at that meeting. And we drew up a constitution. And Ken Burns was elected our first President. And we had a coordinating council, and I was named to it, I’m sure. And we—I still have the Mattachine seal here. And I don’t know whether it’s really, absolutely, technically alive in the State of California, but we still operate as the Mattachine Society, Inc. It’s a corporate entity that does service, particularly things like these interviews, which are important for the history of, the early history of the gay movement.[8]The Mattachine Society, Inc., C0284348, was registered with the California Secretary of State on 23 Mar 1954 by Hal Call. Its last Statement of Information (SI) was filed on 03 Jul 1989. Currently … Continue reading

We were not—we were not really doing that. We opposed, we opposed what was going on. It was the secrecy and the possible Communist backgrounds that the people were Harry Hay and his five or six or seven friends that comprised the Fifth Order of the Mattachine Foundation. And they gave the Mattachine Foundation to a democratic Mattachine Society at that meeting. And we drew up a constitution. And Ken Burns was elected our first President. And we had a coordinating council, and I was named to it, I’m sure. And we—I still have the Mattachine seal here. And I don’t know whether it’s really, absolutely, technically alive in the State of California, but we still operate as the Mattachine Society, Inc. It’s a corporate entity that does service, particularly things like these interviews, which are important for the history of, the early history of the gay movement.[8]The Mattachine Society, Inc., C0284348, was registered with the California Secretary of State on 23 Mar 1954 by Hal Call. Its last Statement of Information (SI) was filed on 03 Jul 1989. Currently … Continue reading

Absolutely.

And we still make referrals, and we still do other services, and so on. And we are—it is a committee, now. It’s sort of a permanent committee, and the committee is, for the most part, myself and my staff, down here. And it’s still alive. Still going.

Ken Burns was a—he was a safety engineer for the Carnation Corporation. [Pause] He was a safety engineer for Carnation. He was—I think he was just about to become a seminarian in the Episcopal order of the church. And, of course, gay, and very personable. And our first president. Now, he’s not been active in Mattachine in any way, except maybe very locally, for the last 30 years.

Right. Jim Kepner was kind enough to give me an address for him. I just haven’t had a chance to—I have so many people in the L.A. area.

I don’t know that I have an address for Ken, but he’s still alive. Now, Marilyn Rieger left right after that little convention. She left our organization. She was, again, I think, the treasurer of something in Los Angeles, or something.

Jim Kepner said something along the lines of her going to the Hare Krishnas, or something like that?

She might have.

That he and Dorr found her at some point?

Well, I think she got into some other religion, or cult, or whatever.[9]It was Self-Realization Fellowship, as recalled by Kepner, who also recalled that he and Dorr Legg had an encounter with Riger at the airport.

That’s what I understand.

Now, I don’t mean to say that in a negative way about her, no.

No.

Boopsie, wasn’t it [her nickname]?

Yes. OK.

On ONE

Now Kepner was busy with ONE during those years. An avid book collector. I’m sorry that Kepner and Slater and the ONE people couldn’t stay unified.[10]Cain italicized ONE, indicating the magazine, but Call appears to refer to the organization ONE, Inc. rather than the publication ONE, at least in the second instance.

I talked to both of them [apparently meaning Jim Kepner and Dorr Legg] about that. And they seemed perhaps not as antagonistic as I thought they might have been about the possibility of the collections eventually finding their way to one another. I haven’t talked to Don yet. I hope to talk to Don.

And you’ve talked to Dorr. I helped ONE, Inc. manage to get that campus. I made a loan to them.

Oh, yes! Yes, and he mentioned that.

Because I’m a trustee of ONE. But ONE, Inc. is not going to get off the dime. They’re going to have problems, and crises, from now on. And when Dorr’s gone, I don’t know what’s going to happen. Unless they can create something that brings in a daily cash flow. Be it a thrift shop, or start a bookstore, or whatever. It[’s] gonna have to be some kind of a thing that brings in some cash every day. And not out there at that campus at Arlington Hall.[11]Call refers to the house on Arlington Avenue, Los Angeles, quarters of ONE’s non-profit affiliate Institute for the Study of Human Resources (C. Todd White. 2009. Pre-Gay L.A.: A Social … Continue reading

Yes.

And I don’t know—Dorr Legg may be the stumbling block, that you cannot establish something of that sort as long as Dorr’s alive. I don’t know.

Dorr seems to be pretty set in his ways.

I know. He’s very set, and I understand the people that had ideas and want to do some things around ONE, they get shot down by Dorr, who will—he just won’t give up control of anything down there. Well, I adore Dorr Legg, all right. But ONE has got to have some, an entrepreneurial enterprise established on its behalf that will bring in cash, a cash flow, or it is going to be, it is going to collapse. And that fabulous collection— and God knows what will happen to it.

Yeah. Since you came into Mattachine around the beginning of 1953, maybe the tail end of ’52 . . .

No, it was ’53. Beginning of February.

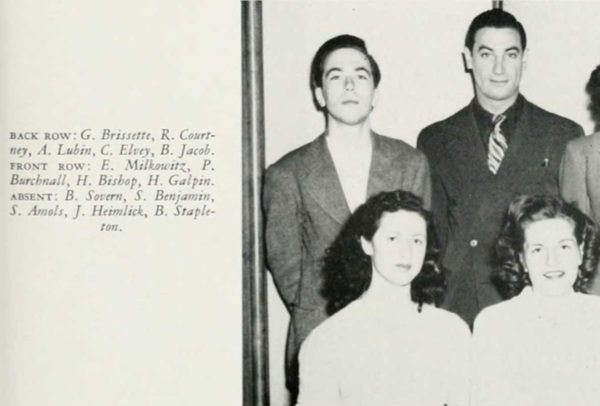

On Gerry Brissette

Did you know Gerry Brissette?

Yes.

OK. Can you tell me anything about him?

Well, Gerry Brissette was the one that made the first contact with the Mattachine discussion group in Berkeley, and how I met Gerry Brissette, or heard about him, I don’t know. But then I think it was through him that we heard about it, and went over to Berkeley, and that’s where we got the idea.

That’s what I thought. How—what—I understood he had like three different groups going on in the East Bay, and then you never hear anything about them. Did they just . . .?

They just kind of petered out. We had established some small chapters here in the, on this side of the Bay. I was interested in establishing—well, the first group was called the Alpha Group. And that was our main discussion group. And I just, I helped establish a Beta Group that was concerned with creating a newsletter and starting publications. Because my field is journalism and printing and publishing newspapers. And the way you get the word out is in the printed message, in those days. And so that’s what I knew had to happen. And in September 1953, on a mimeograph, we published the first San Francisco newsletter, of which I don’t have a copy. And I don’t know whether there’s one in existence. It was mimeographed, I think six 8½ x 11 pages of mimeograph. Of what we were doing, and what our aspirations were, and so on. And we typed that out.

Did Gerry Brissette just drop out?

I think he dropped out. He was involved in children’s drama, or . . .?[12]Brissette had “until recently” directed an off-campus (UC Berkeley) group of Methodist students who were interested in religious drama (Brissette to Chuck Rowland, 01 Mar … Continue reading

I have no idea. I haven’t found much about him.

On David Finn

Now, David Finn was—he hasn’t been among us for a good many years, but David Finn was more interested in some real estate things, and stuff like that, and he sort of dropped out. We had a lot of people who’d come in to Mattachine, and these others who were sort of comfortable with their homosexual orientation, and when they sort of solved their own personal sexual orientation questions, they dropped off. So all the time, we were having an in-and-out of new members. And that’s why I made those references to the newest wave of new members. They’re the ones that had the problems! When they resolved their problems, sort of, why, then, they fell by the wayside!

Right.

I mean, that’s what—we knew we had to have a steadfast core. The main thing was the continuity. Because otherwise, why, it would be a sort of thing that would never have any substance.

Right.

On the Mattachine Founders

How about Rudi Gernreich, Bob Hull, Dale Jennings?

Dale Jennings was the one involved with, in a[n entrapment] case in Los Angeles.

Yes.

Bob Hull was one of the original foundation people, and he is—he’s been long dead. Or has died. The other one, I don’t know. Who’s the other one?

Rudi. That was Harry’s lover at the time.

I don’t know.

And then Harry and Chuck.

Well, Chuck Rowland never did, was happy about me.

I know. Yes. Your feud was pretty legendary, I think.

He was jealous. Chuck’s all right, a smart guy, but I think he was rattlebrained at times, and I think he also had that—he had that Mattachine Social Order, or suborder, in society . . .

[End Tape 1, Side A]

[Begin Tape 1, Side B]

We were talking about Chuck Rowland.

Yeah. He had that idea of the gay suborder in society that I didn’t share. I think Chuck did. Chuck was all right, but we never were, we never related or worked together on anything.

Right. Now, I remember reading, again in Eric Marcus’ Making History, he [Chuck] had a lot of unkind things to say about you, but I think the thing that bothered me the most was, he was talking about once you had control of Mattachine, that sort of the rest of his life fell to pieces, in effect.

[Laughs]It seems—when I talked to Jim Kepner, he seemed to think that it was more when he was—when the Church of One Brotherhood didn’t survive.[13]Here and below Cain capitalized ONE, as in ONE, Inc., but the name was Church of One Brotherhood; see this finding aid at ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives. That that was really more of the bigger blow to Chuck.

It might have been. To Chuck, yeah.

Do you have any . . .

The Church of One Brotherhood was a very short-lived thing.

Right. It was only about a year. But according to Jim, he said it was going great guns, until suddenly one day, for reasons that nobody could ever really put a finger on, the bottom just kind of dropped out of it. And that that was the thing that, really, you know, that Chuck never recovered from.

I never really knew much about the Church of One Brotherhood, except that it did exist for a short time. Now, that was long before Troy Perry and the MCC came in.

Right. It was like ’56. Yeah. And then Harry.

Well, Harry Hay. He and I are—were friends, good friends. I adore Harry Hay, for his creating the Mattachine idea and the name. And otherwise, Harry is—to me, he’s an erudite, [Laughs]

Someone remembered him as a dilettante.

Yes! Way off on something else, you know.

[Laughs]

He can’t get down to earth on anything! And that’s just the way Harry is. That’s not necessarily a criticism.

Right.

And Harry had the idea, but he couldn’t do doodly-damn with it!

Right. He didn’t have the background to be able to pull it off.

He didn’t know how! And he didn’t have the inclination. Oh, he wanted the circle of friends around him, you know. That’s Harry. He wants to be in the middle of a circle of friends, period.

The Circle of Loving Companions. Yeah.[14]Cain refers to the “collective” that Hay founded in 1965, which later was joked about because “for long stretches” it included only Hay and his lover John Burnside, i.e., “a … Continue reading

Loving companions.

On Wresting Control

All right. Let’s talk a little bit more, still in the same area. I’m curious why you were so determined to wrest the control of the Mattachine Society from the founders. Was Communism really the reason, or was there . . .

Well, that was one of the reasons. It was that, and they didn’t know how to do anything with it! They had no concept of what to do to expand it, and to protect the security of those who came to it, and at the same time, connect with people in the major society, in the professions, in law, the judges, the courts, in law enforcement, in the academic world, and in the world of writing and literature and research, behavioral sciences, and so on. We had to work with people in all those. And as I have been quoted, sort of derisively at times, I’ve said, “We have to ride on their shirt-tails.” Well, God damn it, we did! We didn’t have doodly-damn any substance or wheels of our own.

Right.

We didn’t! As soon as someone came in and snapped their fingers, boom, we were shattered and gone! We had to get the recognition from established elements in the total society that we were human beings, different mainly only in the, our choice of a sex object. That we came from the straight world, and were a part of it, and there were so many of us that we were not going to go away, as long as babies were going to continue to be born. And there was nothing that anybody else had to fear. Because at that time, I myself knew that I didn’t—that I had always been homosexual. I tried not to be; it didn’t work. And I’ve never known anybody, ever, to be converted to homosexuality by a[—]one or more than one homosexual act, or expression.

Encounters. Right. Right. I agree.

But you can’t get the straight world to look at it that way! All they can do—I think now, it’s a prevalent thing, that most non-homosexual people, and the anti-homosexual leadership, seems to think that gays can’t wait to get to either be fucked in the ass or get fucked. Anal intercourse. And I know a vast number of homosexuals, and they come to this club [Circle J Cinema], who have no anal orientation. It’s repugnant! And those that have the heavy anal orientation, that I’ve known, and there’s dozens and dozens of them, are dead from AIDS!

Yeah.

And those that don’t are still around.

Today.

Yeah.

Yeah. The Encyclopedia of Homosexuality described your program in Second Mattachine, which is what they called it, as “assimilationist.” Would you say that’s a true . . .

We tried to assimilate into total society. Yes, that was a goal.

How did you take so much power in Mattachine so quickly? If you attended your first meeting in February ’53, and basically ran the founders out by May? You must be damn good.

Well, I was! [Laughs] I was young, and I was handsome at the time, but also I was a journalism graduate, from the University of Missouri, and I knew what I was about, and I knew we had to have publications, and that we had to have a steady core of leadership. And it was going to be a full-time project, and we had to do something that we could pay ourselves and survive, and do this. And stand up and be who we were. And be counted! And not be the furtive, fly-by-night people that are always hiding under a rock.

Did you ever think that you could ingratiate yourself into the Fifth Order and be able to . . .

No. I didn’t think—I didn’t have any affinity for that organization at all, ever.

[Laughs]

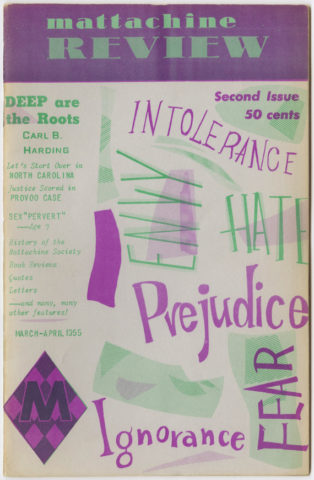

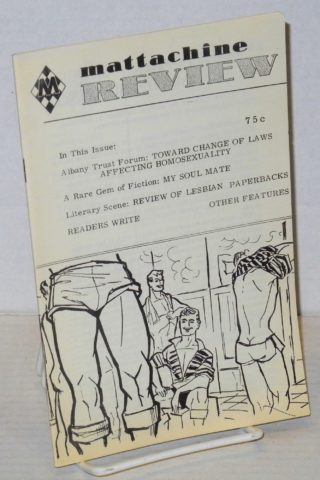

On the Mattachine Review

I knew this. That there were others that were going to come on the scene, and look at what was going on, and think that maybe—they thought maybe I was having a field day, you know, being influential in the Society. And incidentally, not until Mattachine was almost disbanded here, in the active sense, did I ever become its executive director, or leader. I was publications director. I edited the Mattachine Review. That was our voice. I edited that for twelve years. Well, now, that soaked up all the steam I had, really. That twelve years, in those days.

Right.

And it was the second significant gay publication in North America, and it did its thing. But it was also a labor of love, and I did some writing for it. I used pseudonyms, generally, when I wrote. And it’s because I didn’t feel that the editor of the magazine should be having, using his own byline. And we wanted to have the various reports and items and articles in the little magazine. We wanted them to have a name behind it. And we ran a series of the photographs of the leaders of the Mattachine Society in the Mattachine Review. Ran their pictures. Gave their true names and their biographical data, and so on. Myself, Don Lucas, Conrad Bowman, who was our treasurer—and he’s still alive, too. And others. I’ve forgotten who-all we did have, in a series of articles, and photographs and biographical data. So we were not hiding behind a pseudonym! And I never, we never experienced any, any real discrimination, difficulties. It’s true that later, when we had the bookstore up here, the police made a bust on us for selling heterosexual, a fifteen-minute, heterosexual, 8-mm movie. And they did it just to prove they could. It was a routine thing for them to do. And Don Lucas—well, Don Lucas sort of copped out on it, I think. I didn’t. There’s never been a conviction against me on anything. And that’s the only time in connection with Mattachine I’ve ever been busted, because of this bookstore thing. But we—I think one of our greatest accomplishments, of mine, was that court case in Minneapolis that opened the door for some erotica to go through the mail. Male nudes. Very important. Yes. That developed into a multi-billion dollar industry, in North America and the world.

And it was the second significant gay publication in North America, and it did its thing. But it was also a labor of love, and I did some writing for it. I used pseudonyms, generally, when I wrote. And it’s because I didn’t feel that the editor of the magazine should be having, using his own byline. And we wanted to have the various reports and items and articles in the little magazine. We wanted them to have a name behind it. And we ran a series of the photographs of the leaders of the Mattachine Society in the Mattachine Review. Ran their pictures. Gave their true names and their biographical data, and so on. Myself, Don Lucas, Conrad Bowman, who was our treasurer—and he’s still alive, too. And others. I’ve forgotten who-all we did have, in a series of articles, and photographs and biographical data. So we were not hiding behind a pseudonym! And I never, we never experienced any, any real discrimination, difficulties. It’s true that later, when we had the bookstore up here, the police made a bust on us for selling heterosexual, a fifteen-minute, heterosexual, 8-mm movie. And they did it just to prove they could. It was a routine thing for them to do. And Don Lucas—well, Don Lucas sort of copped out on it, I think. I didn’t. There’s never been a conviction against me on anything. And that’s the only time in connection with Mattachine I’ve ever been busted, because of this bookstore thing. But we—I think one of our greatest accomplishments, of mine, was that court case in Minneapolis that opened the door for some erotica to go through the mail. Male nudes. Very important. Yes. That developed into a multi-billion dollar industry, in North America and the world.

I read in a little book I found called Homosexuals Today – 1956, that was put out by Dorr . . .

Yeah. ONE, Inc.

. . . where you said the Mattachine Review was in more than a hundred newsstands coast-to-coast at that time. Was that true? And if so, where?

Well, we had one on Third Street. We had City Lights here. Ferlinghetti and City Lights. Lawrence Ferlinghetti was always favorable. And we had a distributor in Cleveland that was supposed to be putting it into a number of bookstores in the east. And they were taking so many copies—they were doing something with them, and we never got—we kept sending them copies, and we never got any money. Fifty cents was the sales price for it at the time. And I don’t know whether we really had more than a hundred bookstores or not. That may have been an exaggeration.

I was just curious, just because of the times. I mean, in 1956, it was difficult for me to think that that quickly, especially because, as you said, it got off the ground in ’55, and would have spread . . .

’56. I don’t think it did. Now, ONE, Inc. had a newsstand distribution, but—our distribution was, you know, whatever theirs was. It was just about parallel in that period. And ONE Magazine was—sort of just played itself out at about the time Mattachine Review did, in the late Sixties. 1967.

Right. I think I know the answer to this, but I’ll ask it anyway. Do you feel that, given the times, you made the right decisions regarding Mattachine’s direction in the mid-to-late ’50s? And then later in the mid-’60s also?

On Second Thoughts and Cinemattachine

Yes. I think we did the right thing. I think, as a pioneering organization and getting certain things started. What we wanted to occur was more organizations take place, more homosexuals come forward and lead project groups, and make news, and stir up shit, if you want to say it! And get into the printed newspaper and magazine press, of the time. And as television was coming on, even get into that. Because we knew homosexuals were everywhere. When I worked for the Kansas City Star in 1950, I knew that the Kansas City Star wouldn’t be able to get the paper out if all the homosexuals were taken off of it. They were everywhere, from the press room and linotype machines clear on up to the executives in the advertising department, and so on. And we knew that there were gay people everywhere, and we wanted to see evidence of that, you know, shown to the public anywhere and everywhere it could.

Why did you ultimately send the Mattachine toward Cinemattachine?

Why did you ultimately send the Mattachine toward Cinemattachine?

I tried—we wanted, we had to earn money. And we had the bookstore going, and I wanted the protection of the organization of the Mattachine Society, to be an umbrella for showing gay erotic movies, because we were pioneering in that, in 1970, in San Francisco. And I—I thought the word “Cinemattachine” was clever. It had the word “cinema” and “Mattachine” combined. But it was a mistake, because nobody could pronounce it. I’ve had more people going “Cinema-ma-[gibberish]”; you know, they’d get tongue-tied on the words. “Cinema-ma . . .” Cinemattachine. Mattachine cinema. And it made a long word; too many letters in it. I don’t know, there might be twenty letters in the word.

[Laughs]

But we were using it, and we soon got out from under that, though, and became Circle J Cinema. Now in the Seventies, Mattachine met with our police department, and district attorney’s office, and a representative from City Hall here in San Francisco, and we pushed through the idea of having private gay jack-off sex clubs.

Right.

That the police would not bother us. We said they were good for mental health, and they—and the police needed to spend their time doing things other than watching people play pee-pee, and trying to catch that. We were—in fact, the newspapers and the television stations were beginning to laugh at, to make fun of our police department, that it was—making only morals arrests. Well, they did. They set up the guidelines. District Attorney Joe Freitas. And we’ve had the gay sex clubs ever since. With—and with live stage performances. We had the first live stage performances, in the mid-Seventies, when we were across the street. [Unintelligible] jerk-off show at nine o’clock at night. And I was not one to get too big for my britches, and we know there are too many entrepreneurs on the gay scene today. The gay entertainment scene, and the film production scene, and so on. They are greedy beyond—well, beyond decency.

Right.

And I don’t think we’ve ever been that. But we have been showing gay movies here for 21 years, and we’ve not had any problems, nor has anybody coming to these movies had any problems from it. So I think we’re doing something right.

Right.

And it’s good for mental health, or it wouldn’t continue.

Absolutely. Who is on the current Mattachine corporate board?

I’m Executive Director. Don Lucas is still on it, and Ben Heath downstairs, that introduced you and let you in, is on it. Lon Ferris, a man I’ve lived with for 22 years. We’re friends, closest friends. We’re not sex lovers. Is on it. And that’s about it. Oh, Ed Milner, who does accounting for us here, is on it. Those are the members of the Mattachine board today.

OK.

We have an annual meeting, you might say, to officially try to say that Mattachine is alive.

Right.

There [on the wall] is the banner of the Mattachine Society.

That’s what I thought, yeah.

And that was made by a heterosexual woman. She was the mother of—her name was Mrs. Leah, L-E-A-H, Gailey, G-A-I-L-E-Y. And she was the mother of Ray Frisby. One of our members.

Ray Frisby or Fred Frisby [sic]?

Ray. Fred Frisby’s in Los Angeles. There was a Ray Frisby up here. Fred Frisby’s a good man in L.A. I know Fred. But Ray Frisby was a member up here, and Ray was—oh, Ray was always heavy into jerk-off. And he still comes to this Circle J Club.[15]Jim Kepner calls Fred Frisbie “probably the senior activist in the United States” and tells an amusing story involving him and Stella Rush (aka Sten Russell).

For heaven’s sake.

And—yeah. He may be—he’s in his upper sixties, anyway. Today.

Uh-huh. That’s great!

She made that banner. Now it’s faded a lot, because that was very rich blue and silver, and a very rich golden “M.”

Ah.

That’s the original Mattachine banner, right there.

That’s great, yeah. That’s wonderful.

Captain’s flag. [Laughs]

All right. You were talking about Richard Inman a little while ago. What can you tell me about him, if anything?

Well, he was in Florida, wasn’t he?

Yeah.

He did work in trying to get the Mattachine idea started, and get people together under its auspices, and, you know, for . . .

Do you have any idea whatever happened to him?

No. No. He visited us, I think, once, or maybe more, out here. I don’t know that I ever visited him in Florida or not. But I remember Richard Inman.

The one person Jim Kepner said I might get in touch with him through is Jack Nichols, and he had an address for Jack.

I don’t know who that is.

OK. How about Elver Barker, who was in Denver?

Elver Barker was in Denver.

On the Mattachine Convention, 1959

Can you tell me anything about the Mattachine meeting in ’59?

Oh, yeah. I was at that convention.

Yeah. They made quite a deal over that.

We did. We had this—do-gooder, con artist of labor unions and so on, a gay man that was with us. William Brando was his name. And he saw the Mattachine thing as something—he was homosexual, but I didn’t even know. And he was an entrepreneur and a promoter, this Bill Brando. He had a little money or something. He was—he caused us to have—he let Mattachine have a court reporter or something at the Denver convention, and take down the minutes of our meeting. First time that was ever done. And it came out, the pages printed on a ream of paper, printed on one side. He brought that back, and he had some copies of it reproduced. And he said—unknown to us, Bill Brando was going around and sort of trying to promote something for himself out of this, and that’s why he took it to the Wolden, Russell Wolden political offices, to try to make it, sell it for some money to show . . .

Wow!

Wolden could nail the incumbent mayor, George Christopher, as coddling sex deviates in San Francisco with their national headquarters here, and then they had just had this big annual meeting in Denver. Oh, my God, in Denver, we had professors from the University of Boulder, Colorado, at Boulder, and I think maybe DU as well.

There were some politicians, too.

Politicians, and so on. And it got favorable—it got favorable coverage in the Denver Post! I was interviewed on a lot of these things, and I made it so that we had favorable coverage. And I knew how to be interviewed, and what to say.

Right, right. That must have been quite a P.R. coup for ’59.

It was! It was. Well, then, when we came back here, Russ Wolden gave [unintelligible] about Mayor George Christopher. Well, Christopher was hanging on a hook. We were hanging there with him. And this when we made our first close connections with the police department in San Francisco, and they got busier, and set up a kind of a permanent liaison section in the police department that had officers have a liaison with the gay community.

Right, yeah.

And we were—when the true story was told, why, it made Russ Wolden’s side look like a bunch of thieves and rogues, you know. And Russell lost that election, by the largest majority. He lost it by the largest margin of any major candidate so far in this century.

Wow!

Time magazine had, there was an item that mentioned the gay thing in San Francisco’s mayoral election, and there was a statement made, something like, “And up on Broadway, where Finocchio’s and other sex shows, and so on, were going on, somebody asked who won the election for mayor. And this person said, ‘I don’t know, but they’re having the damnedest celebration at Finocchio’s you ever heard!'”

[Laughs] That kind of answers that question.

Answers that question.

On Clark Polak

How about Clark Polak? Did you know him?

Yes. Well, he was in the New York group that an attorney, Kenneth Zwerin, used to be a gay attorney here, who wanted to be pushy one time and take over me and the Mattachine, in a way. We had various artists come our way, and want to take over. They’d visualize something that they could make money out of, maybe. And Hal Call generally got to see through those plans in a hurry, and quash them. Well, there was the idea in New York—I’ve forgotten the young man’s name who was president, but—and Clark Polak and another person in New York were some of the leading New Yorkers, and they wanted to take over Mattachine and carry it back to New York City, because, after all, New York City [unintelligible] the Mattachine, but New York City can never be the branch office of anything! It’s either head office or nothing. And they were [unintelligible] to do that. Well, by God, they didn’t accomplish it. I didn’t let ’em.

What period of time are we talking about there? Mid-Sixties?

Early Sixties. Very early Sixties. About 1960 itself.

OK.

Yeah. No, I didn’t let ’em do it, because—no. And they went ahead on their own with some things, and it didn’t bother us out here any, to speak of. And they went ahead and created the Niagara Frontier group, with some discussion groups along, from Albany and Rochester and Syracuse, the upstate cities, and the New York City Mattachine entity. Which was all right.

Sure.

Let ’em go.

If I remember correctly, Jim Kepner said that he committed suicide. Do you remember that?

Polak?

Yeah.

I don’t know.

OK. I just wondered.

I don’t know.

On Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon

How about Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon? I’m sure you’ve known them for a while.

They’re still here.

Yes, they are.

They’re still here, and Phyllis and Del, I love ’em. I must say this, that in the last years, very recent times, the lesbian, along with—she’s tied, the lesbian woman is tied thoroughly into the women’s movement, which has been coming forward in the last few years. And, believe me, they have run circles around gay males in publicity, in getting attention, and in gaining acceptance. The lesbian doesn’t have the, she doesn’t have the difficulty in being accepted that the male homosexual does. The male homosexual is a threat to every other male in our society. And the lesbian is not. Because the males in society, that regulate us, acceptance, and [unintelligible], you might say, they know that no lesbian would be a lesbian and go lick at each other’s puss[y] if he could just give them one good fuck. They would be heterosexual from then on. That’s all they were lacking, is one good fuck. That’ll convert ’em from lesbianism. Now, that’s the average male concept of what it’s about.

Correct.

And [Laughs]—When Del and Phyllis have—they’ve been instrumental in making a lot of advances and in being respected and remembered in a lot of ways that we in Mattachine have not. One of the reasons that became a stigma on our back,[16]Call interestingly uses a phrase that recalls the groundbreaking lesbian erotica periodical On Our Backs, a play on the feminist newspaper Off Our Backs. and still is, is the fact that we drowned ourselves so heavily in erotica, and reading erotica. And, to me, in San Francisco, although I know and contribute to political campaigns of people like Dianne Feinstein and our members of the Board of Supervisors, and I knew Harry Britt, and I knew Harvey Milk and all of those people, I still am—and I’m connected with gay sex. I’m a sexualist. I’ve always said, We’re fighting for sexual freedom. Let’s have some. Now, turn this off a minute. I’ve got to do something.

Sure. End tape.

[End Tape 1, Side B]

[Begin Tape 2, Side A]

Did you criticize Phyllis and Del for holding the first DOB [Daughters of Bilitis] convention in 1960? They seem to think that you did, in Lesbian/Woman.[17]Del Martin and Phyllis Lyon. 1972. Lesbian/Woman, San Francisco: Glide Publications.

I don’t think so.

OK.

I’ve never—I would never opposed anything that DOB was involved in, or doing.

Let me see if I can find the direct quote. Just out of sheer curiosity.

I’d remember that. I don’t remember.

Right. Well, as I’m saying, that’s—let’s see, here we go. “As a matter of fact, when DOB held its first national convention in San Francisco in 1960, Hal Call, Mattachine’s president, wrote us a letter criticizing us for calling it, in our publicity release, the nation’s first lesbian convention.” This is out of Lesbian/Woman, that they wrote.

I wasn’t Mattachine president, either.

True. [Laughs] I mean, I wouldn’t doubt that it could be wrong. I just wanted to show you what the source was that I had for it. Some quotes are more memorable than others.

That’s not even—that’s some people that I’m not even aware of.

That’s fine. OK.

No.

On Men and Women

I would feel this, or I would have had this feeling in those days. Male and female homosexuals could and should be in one organization. But the female homosexual had a whole different set of problems from the male. In that the male had most of the opprobrium from society at large, and we were receiving more attention from males. We had minimum participation by females in the Mattachine. Never did have any to speak of. ONE, Inc. had a few lesbians that were in and around the magazine. But there was never any real heavy leadership developed on the part of any females in ONE. They—that’s when DOB got its own organization. I’ve never opposed them at all.

Right. You mentioned in, again, in Marcus’ book, Making History, “The women weren’t in the early days of the gay movement. And they didn’t have any problems compared to what the male did.” Maybe the women weren’t getting the police harassment the men were getting, but they sure weren’t getting any support from the larger community, either. Didn’t that ever seem to concern the men? I mean, very few of the homophile leaders really seemed to give a damn for them, and I would have thought that they would have worked together as a more natural constituency.

Well,—the homosexual problem in the 1950s was a male problem.

But I think of even someone like Barbara Gittings, who said when she came out there was nothing to come out to.

That’s right.

You know, so—I mean, it was a problem for the women, but not the same way. I mean, they weren’t getting busted by the cops, but they had no way of being able to . . .

We didn’t know there were that many lesbians, even, at that time. I don’t think the male homosexuals knew. And at the gay bars we had in San Francisco at that time, there were very few women. And maybe there was one women’s bar, somewhere out here in the Haight or somewhere, maybe.[18]Call could have been referring to the Whoo Cares, a bar at 782 Haight that had been open since 1951, according to the Bay Area Reporter. I don’t know. But we never heard much about lesbians. The closest thing we heard about were males trying to be females.

So, what you’re saying is the gay men’s community was as ignorant about the lesbian community as general society at large.

Right.

Sure. And that makes perfect sense, then, if you think about it. OK. Makes sense.

On Barbara Gittings

I was going to ask—oh, OK. Barbara Gittings, since I mentioned her, and Kay Tobin Lahusen. I’m set to see them next month also. Do you have any remembrances of them? I know you introduced Barbara to, what was it, the—did you introduce her to DOB?

I could have.

Yeah. I think she mentioned you.

Barbara, was a—Oh, she was a horse of a woman.

[Laughs] That’s the same story I get from Jim Kepner!

[Laughs] She could sit down, and she could eat four eggs, and four big slices of toast, and a great plate of hash brown potatoes, and six slices of bacon for breakfast. And wash it down with a glass of milk and four cups of coffee.[Laughs] I can’t believe it! That’s the same story Jim told me! I can’t believe it!

But she was—she was really, she was almost a male in a, a horsey male in a—a male athlete in a female body. Now I—she was a vivacious and energetic and very outgoing girl. But—oh, she was a [Laughs]—she was a grown-up tomboy from the word go.

Everybody mentions that the other thing is, the people I’ve talked to, every seems to really love Barbara.

Yes. She was a lot of fun. Oh, she had everybody laughing and going. And she was in the middle of it all. She was the central conversationalist, and she had everybody rapping and going.

Did you know Kay, her partner?

No.

OK. That’s fine, then. We won’t bother with that.

On Dick Leitsch, Randy Wicker, Frank Kameny

How about Dick Leitsch? Did you know him?

Yes, I knew Dick. Dick was a good man.

He seemed also to come under an awful lot of criticism.

Well, he was President of New York Mattachine, wasn’t he?

Yeah.

Uh-huh. I think Dick Leitsch is one that Ken Zwearin tried to play Dick Leitsch against me, and that this is New York trying to take over the Mattachine in San Francisco. So New York Mattachine didn’t want to be a branch office of—with the headquarters here. And, but Dick was a—yeah, he was a substantial entity.

How about Randy Wicker?

He did some writing, I think. He wrote some for the Mattachine, Randy.

He also did a fair amount of P.R.

Yes. Yes.

He did some TV shows, and things of that nature.

He was all right. Now, I’m not close enough to know much special about him. Or Dick either. I didn’t know them that well.

Right. How about Frank Kameny?

H: Well, I met Kameny two or three times. And I admire the things he’s done, because he was—when something happened, he can step right in and be a real shit-stirrer, and get things going. He got the entire Constitution of the Mattachine Society of Washington, D.C., which was something of his—partly his creation, and the Constitution was a copy of the one we had here, adapted to their local area. He got the entire thing read into the Congressional Record, and it’s printed in the Congressional Record in Washington, D.C. to this day.

[Unintelligible] [Laughs]

And he did that 20 years, 25 years ago. Yeah, he caused it to get into the Congressional Record. Now that’s something.

Yes. Would you describe him as a real dynamo?

Yes.

I mean, I think that fits.

Yes, he is. And he’s been one person that—he uses his title “Doctor,” which is Doctor of Astronomy.

Right.

And he’s not an attorney, but he acts like one, in a lot of ways.

Oh, yes. For all the court cases he . . .

He’s well read, and he knows what he’s doing, and he’s fearless. And he makes sense!

I’ll also be seeing him when I go back next month.

Give him my love and regards. I’ve always admired that man.

You bet! Absolutely. I’ll do that.

We’ve never been close. As a matter of fact, Mattachine has never had the resources, never did have the resources for us to travel and communicate with each other. That’s one of the things we always lacked.

Right.

We never had any rich old—rich old gay farts that die and leave us millions, as should have been done. But it hasn’t. [Laughs]

On SIR

How about—let’s talk about some of the SIR [Society for Individual Rights] people. Bill Beardemphl, Bill Plath, Mark Forrester, Guy Strait.

Well—all right. Now Bill Plath was a Mattachine man.

OK.

But he went over—Bill Plath objected to me, and Mattachine, and my idea of wanting to get a permanent paid staff. Bill wanted unpaid volunteers only! Bill Plath, and Bill Beardemphl, and some others were instrumental in forming the Society for Individual Rights. Somewhat as a protest to Mattachine, but more, also, to expand the idea of homosexual organizations and participation by homosexuals in projects they could volunteer for, and entertainments, and things of that sort. Now, that was the core of SIR. Some of its organizational meetings were held in my flat, up on Pine Street. So I’m not anti-SIR. I had a life membership in SIR! Its publication, Vector magazine, was nice, and slick. And, again, it was being handled by—nobody was paid. But they were beginning to get some paid advertising in Vector magazine, at about the time when—that we, with our printing of Mattachine Review, were running out of steam. And we didn’t have any paid—we didn’t have any advertisers willing to come forward and buy advertising in our publications, which would have given us the revenue to work with. But SIR came along, and did a good job! And we always cooperated with SIR. There was not any heavy antagonism between SIR and Mattachine. The Mattachine was sort of a—had sort of done its thing. And our group of leaders were sort of diminishing in our influence and activity, while their was growing and expanding. But it grew, expanded, flowered, and then it died.

Now, that started about ’61, right?

’64.

Oh, really—OK, OK. And then, when did it kind of stop? ’67? ’68, maybe?

H: Or ’70, somewhere right along there, yeah.[19]The SIR collection at ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archives spans 1964–1977 (see finding aid); at SFPL 1960–1969 (including pre-1964 non-SIR material; see finding aid).

On Guy Strait

What about Guy Strait? Can you tell me about him?

Guy Strait. Guy had a lot of dynamism, and leadership character and qualities. He was heavily turned on sexually to young, young boys. And that caused him to—he got into photography, and all that jazz, and he got a conviction. He served, I think, eight or nine years in the Federal Penitentiary at Joliet. He came out and died soon after that.

Wow!

But Guy wanted to take over Mattachine, and he wanted to create an opposing organization. You know, the gay movement is filled, from the beginning to this present day, with all kinds of individuals who come into the scene with a lot of spunk and spit and Shinola, and all that. And they want to organize the gay community. And they all—their technique for doing it is always to create a new organization and place themselves at the head of it. Yeah, we’re gonna have unity, and we’ll get all the gay people together, and their gonna come together under my organization! And do what I say!

Despite the fact they couldn’t do it under this organization.

No. Even SIR was a product of that. But, nevertheless, there has been a diaspora, you might say, of organizations that created. And we’ve still got ’em. We’ve still got ’em. And now they’re marketing, you know, with professional mailers, and all that. The mailings of some of these organizations that expense out trying to raise money. And I get—I get pleas for money, pleas . . .

Oh, yeah.

Forms for mailing in contributions from eight or ten organizations, it seems like, a week.

Oh, I know. I do, too! And I don’t have a title after my name!

Yeah. So—Guy Strait was one of those that wanted to consolidate everything under his ideas. And, for a while, he published a tabloid-kind of newspaper, with some ads in it, and just typed ordinary typewriter copy, at that time. Now, we didn’t have the printing devices, and the computers, and so on that we have today.

This would have been other than Vector?

Yes.

OK.

It was the LCE News. League for Civil Education.

Oh! That’s right, that’s right.

League for Civil Education. That’s Guy Strait. But Guy now has been dead for four or five years.

Jim [Kepner] also told me that he had something called DOM Publications, for Dirty Old Man?

Well, yeah. He had—he had a photo album of boys, photographs. That was his—sex photos.

OK. OK. What about Vanguard? Can you tell me anything about that organization?

Vanguard?

Yeah.

It was sort of incidental here, and it didn’t last long. Now, I don’t know much about it, but here, here’s—I found this somewhere the other day. [Hands me a copy of Vanguard magazine] Don’t even know when this came out.

Ah!

Well, you can have it.

Terrific! Thank you!

I don’t know anything much about Vanguard. It wasn’t—no, it wasn’t more than two drops in the bucket.

OK. But nonetheless—

Would you like a Coca-Cola or anything to drink?

Some water would be great. Thank you.

I’ve got you a cup here—here’s some water.

[Break]On Erotica

I want to make a statement.

Sure.

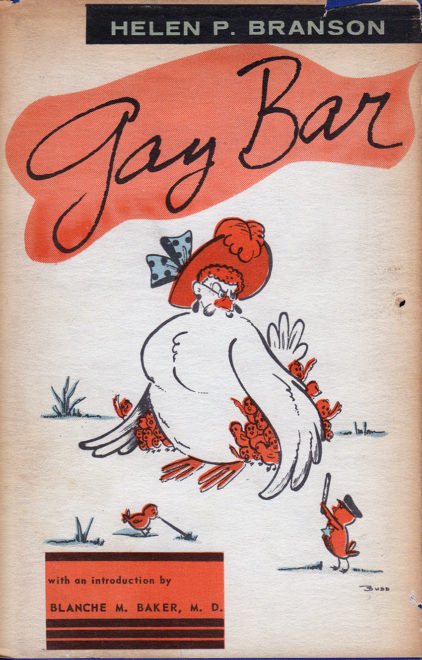

I want to make a statement about literature and erotica that’s come to pass in the last twenty years. Universities, and city libraries, and the academic world, and the behavioral science world, and museums, and so on, treated the huge growth and flood of sex, sexually erotic materials, heterosexual and homosexual, that developed after the late 1960s. They treated it as junk, flowing into our society, and on our, on the cultural scene. They never collected it. The ONE library, in Los Angeles, did. There were thousands—there were different one-handed readers, I called them. Books you read with one hand, you know, while you masturbate with the other. And they were printed on pulp paper, and treated as such, and—they were treated as material that was insignificant. Until now we realize, this is a valid part of human expression, whether we like it or not. It is; it’s gonna stay here; they’re not gonna change it; and we might as well accept the fact that it’s real, and cope with it.

I want to make a statement about literature and erotica that’s come to pass in the last twenty years. Universities, and city libraries, and the academic world, and the behavioral science world, and museums, and so on, treated the huge growth and flood of sex, sexually erotic materials, heterosexual and homosexual, that developed after the late 1960s. They treated it as junk, flowing into our society, and on our, on the cultural scene. They never collected it. The ONE library, in Los Angeles, did. There were thousands—there were different one-handed readers, I called them. Books you read with one hand, you know, while you masturbate with the other. And they were printed on pulp paper, and treated as such, and—they were treated as material that was insignificant. Until now we realize, this is a valid part of human expression, whether we like it or not. It is; it’s gonna stay here; they’re not gonna change it; and we might as well accept the fact that it’s real, and cope with it.

Jim Kepner has quite a lot at IGLA [International Gay and Lesbian Archive, forerunner of ONE National Gay and Lesbian Archive], also.

Well, all right now. Those collectors of this material are getting students from UCLA and USC and Southern California. They’ve come from Stanford and Cal here, and so on. Looking up these collections, and are doing various research subjects involving them. The libraries, university libraries, don’t have this kind of stuff. It was crap. They didn’t want it. Now, they wish they had it! Of course, they got to put it on some kind of —

Microfilm, or . . .

Yes, microfilm, or later, some kind of an electronic medium that will preserve it. So, that’s one reason that maybe it’s a valid thing, that the British Museum might be interested in this gay video collection.

Wouldn’t that be fabulous?

Because it’s real!

Sure.

On Mardi Gras 1965

Let’s talk about the New Year 1965 Gay Mardi Gras in San Francisco. That was the one at California Hall.

Oh!

That people refer to, sort of, as the Stonewall for that year.

What were your recollections of that?

Well, I was there. I was the one—now Del Martin has been quoted as having, or Phyllis [Lyon], as having called the cops. [Coughs] Pardon me. Having called the police. They didn’t do it. I did. [Coughs] The Institute for the National Sex Forum—no, then it was the Council on Religion and the Homosexual.

That’s right.

[Coughs] We held that ball to raise funds for CRH. And that’s the last time the police department in San Francisco made a concerted effort to push gays around. They must have had 30 vans over at that intersection of California Hall. They arrested Evander Smith, and—oh, the other one is Evander’s friend . . .Herb Donaldson?

Herb Donaldson, right. And I got on the phone, and called either Leighton Kirkpatrick or Leighton Elliot, or Elliot Leighton, another attorney. They arrested—I think they arrested a woman named Nancy May . . .

Nancy May, yeah.

She was a woman. She was married to a gay man, Bill May, in SIR. And we did—we did close down the event a little after midnight. And the police were saying that we were congesting—or we were disrupting traffic, and so on. We weren’t. They were! And the television was there, stations were there, and they laughed at the police department! They mocked the police department, which was deserved. And from then on, the cops got out of the business of trying to regulate gays. Gay meetings and gay functions and celebrations.

Well, the ministers who were there, and their wives, held a press conference the next day, right? And were talking about the way that everyone had been treated, and that it was unfair, and so on.

Well this, to me, was part of the things that were necessary for homosexuals to do to get sustained, respectful recognition in the community. Riding—this is a case of riding on the shirttails.

Right.

When we got the Council on Religion and the Homosexual, when we got ministers from the Lutherans, Congregationalists, the Methodists, Universalists, and those kinds of—the [American] Friends Service Committee, the Quakers—when we got clergy from those faiths to stand up and say, “See here. Gay people, gay men and women, are human beings. Let’s treat them as such.” That we had —that was an advancement.

Right.

Then, the press and all the other bigots, and so on, had to stop, or slow down, their criticism. Of course, they’ve not given it up yet, the Pat Robertsons and Jerry Falwells are still with us. But that was a great accomplishment, was to get the Council on Religion and the Homosexual going. Because by then, when that happened, then the newspaper could rub elbows with those clergymen, and talk about this issue sensibly. And so could the radio and television media. That was a big turning point in our progress, right.

The documentary Lewd & Lascivious (2012) tells the story of the 1965 raid on a private masquerade ball in California Hall. See also this Bay Area Reporter story.

Sure. Anything else?

And that was long before Stonewall.[20]Several archives contain CRH material, beginning in 1964.

Oh, yeah.

Of course, we were going here with a gay movement 19 years or so before Stonewall.

Right, right. Yeah. Is there anything about that particular event that happened that hasn’t been talked about before? Anything you can remember that was more noteworthy that hasn’t been mentioned?

No. They never made any mass arrests. They caused us to close it down early.

They said there were about 500 people. Was that correct?

Or more. I never [unintelligible] that. The very fact that the police were there in force, though, from the very beginning of the evening, put a damper on some people’s attending.

Sure.

They didn’t want to go in on something where everybody was going to be swept out and raided and herded around. But it told our police department once and for all, the city, its newspapers and television and radio stations, told our police department and City Hall, “Get off the backs of the queens!” Quit wasting our money and our time with our cops doing that! OK. And from then on, they’ve had to follow that policy that we set.

On Morris Kight

OK. Morris Kight. Now Morris is one of the very few people that you mentioned who should not be, in your opinion, in the Top 100.

Morris Kight is—certainly, he’s a very prominent spokesman. In fact, you can’t get Morris to shut up.

[Laughs]

But he’s a Johnny-come-lately, and he claims that he was here from the beginning, and there it is. It’s a big lie, and a lot of bullshit.

Yet Morris takes very great objection to that, saying that he chose not to work with the organized movement because it was so hidebound, because it was so assimilationist. That what he knew that the movement needed was more action, and less people trying to, you know, do these sort of namby-pamby kind of things that weren’t really getting anybody anywhere. And that—

Morris Kight has gotten a lot of attention that he doesn’t deserve, for just being that way, and I think—I think he’s a crock of shit!

No. That’s fine. Interestingly, though, Morris said that you were a brilliant lecturer. And I have to tell you, that is very high praise from him. So I thought that was rather interesting.

Oh, I’ve lectured in probably sixty different universities and colleges, all the way from Calgary, Alberta to Tulane in New Orleans, Tennessee, Minnesota twice, at the Student Union at the University of Minnesota, Denver University Law School, Stanford, Cal, and all of ’em in California. And Washington, Vancouver. I don’t know where all else I’ve lectured in. But I was an early speaker. But now, I mean, we’ve got—in that period, we only had a very few spokesmen that dared get up on a platform with their right name, and have their picture in the paper, talking about this subject, at that time. Now we’ve got a million of them. Nobody—the thing that used to never, dared never to speak its name now won’t shut up!

Right!

Because of that.

On Harvey Milk

What about Harvey Milk?

Wonderful man. He—because of what happened, he’s become a legend that really wasn’t—that Harvey really wasn’t trying to become. But Harvey is a—I used to buy film from him.

Oh, yeah.

At the camera shop. And we also—Harvey was also speaking—he spoke to other organizations here in town, like the Tavern Guild. Tavern Guild of San Francisco was, incidentally, an important entity in—and Mattachine helped in organizing it. We helped it getting started. And it’s been an important thing, the Tavern Guild of San Francisco has been an important thing. And an entity—organization, with its attorneys and all that, in helping keeping the police in line.

The ABC.

And the Alcoholic Beverage Control [unintelligible]. But Harvey was a—Harvey, he was a good man. And he was a comer. I know one time, I was in a gay bar, before an election he was running. And I met [San Francisco Chronicle columnist] Herb Caen. And Herb Caen was asking me about what I thought about Harvey Milk. They wanted to know, was he just a flash in the pan, or is he somebody that’s real. And I said, well, I think Harvey is going to be very, a very valuable person on our Board of Supervisors, if he gets the seat. And I think he’s a good man, and a balanced person, that wouldn’t go overboard, you might say, in trying to think of nothing but gay issues. No. Harvey was concerned with total community. Its problems. And his political work in City Hall. And his good friend, [San Francisco Mayor] George Moscone—I don’t know if Moscone was gay, but he was certainly warm and friendly to gay people. I never talked to both of them before they were elected. But Harvey—his career was cut so short by his assassination—

Sure. I think, in part, because he really was one of the first gay martyrs. He—

He’s become that, yes.

He assumed a status that might have been very different, had he had to face, you know . . .

Yes. If he had stayed on, and no assassination had taken place, why, we wouldn’t be recognizing Harvey Milk to the extent we are today. Harry Britt, who took his place—well, Harry Britt was no Harvey Milk, although Harry Britt was a good, kind of a good supervisor.

[End Tape 2, Side A]

[Begin Tape 2, Side B]

On Harry Britt

Harry Britt.

He was a Texan. And I think he was clergyman.

Yes. A Methodist minister.

Well, I think Harry did a good job, as good a job as anybody else could do in that Board. On the Board of Supervisors in his time here.

He had some pretty big shoes to fill!

Yes, he did. It seems like nowadays, in our politics in San Francisco, the females, they’ve made inroads into San Francisco like almost in no other city. And, some of the females doing those things are a number of lesbians!

Right. Carole—

Carole Midgen, yeah, I know Carol, and Susan Leung. I know her. And I can give you some of those—in fact, I’m supposed to go to some function, a brunch or something, supposed to do Supervisor candidates. Board of Supervisors. Now, this is coming within a week. And I think Dianne Feinstein did as good a job as anyone could do, taking over as mayor after Moscone’s assassination.

Well, and Jonestown, and, I mean, all of that. See, I lived in the Bay Area, so, I mean, that was a very rough time, I think, for everybody.

Oh, God, yes. Jonestown. Ooh!

Yeah, that was really tragedy on top of tragedy. I’ll be talking to Harry tomorrow morning, I think. Anything, any suggestions, anything I need to know? He seems to be a very nice man.

I think he is. I have no—I have nothing but praise for him, and admiration. He had a hard job to fill, and he’s been subject to criticism by some people that—you know, there’s an awful lot of people in the community who want more than maybe they’re entitled to.

All the time.

All the time. Right.

What—do you have any idea why he eventually—because he became President of the Board of Supervisors, and then eventually—did he step down of his own accord, or was he not elected again, or did he choose not to run?

I think he sort of ran his course.

OK. But I mean, he didn’t, he didn’t go up for election and then was not elected, to your knowledge, was he?

I don’t think so.

Yeah. I’ll talk to him about it. I just wanted to . . .

I think he had done his bit, and it was time to get off center stage.

Absolutely. Absolutely.

On Randy Shilts

Randy Shilts.

Randy Shilts.

Mayor of Castro Street book, and Conduct Unbecoming, and And the Band Played On.

Oh, Randy Shilts, the author.

Yes.