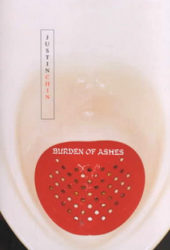

Burden of Ashes

Burden of Ashes

by Justin Chin

Published by Alyson Books

Published May 1, 2002

History (memoir)

224 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

June 3, 2002.

Justin Chin [1969–2015] was a slam poet and San Francisco performer with a lot of grievances, the main ones being with his family, with white men who are attracted to him, and with white men who are not attracted to him.

In the various performances pieces in which I’ve seen him, and the three books by him I’ve read (Bite Hard, Mongrel, Burden of Ashes) there is barely a glimmer that any kind of person exists other than white gay men and diasporic Chinese. I have noticed black people, Latinos, Pacific Islanders, non-Chinese Asians, and women in San Francisco, but Chin does not appear to have. Having been born in Malaysia, where his parents remained when they sent him off to be schooled in Singapore, he occasionally gives signs of noticing Malays, though no sign of recognizing that many of them consider Chinese professionals like his father alien exploiters (in Malaysia) and Chinese an oppressive majority (in Singapore).

It is an interesting phenomenon that gay emigrants from China or Taiwan to the United States have not produced any writers while diasporic gay Chinese from Southeast Asia, whose numbers are much lower, have included several (T. C. Huo, Lawrence Chua, and Justin Chin). And that none of them has acknowledged the resentment for Chinese elites in their native countries while working out in print their own resentments of white folks. Or that none has recognized that ethnocentrism could well be included on the list of “Chinese inventions” (though these authors are removed in place and time from “the Middle Kingdom”).

Chin has his own obsessions. The first half of Burden of Ashes includes horror stories of the sadistic aunt in Singapore who dominated the household nominally headed by a relatively oblivious grandmother. Jamesy, a truly sinister “Auntie Dearest,” had the infamous Singaporean enthusiasm for caning as a punishment. And when the young Justin threw up food he was forced to eat, such impudence was not tolerated: he had to swallow the vomited-up food.

His mother and her sister denied that such events ever occurred. His mother and his sister told him to forgive her, to not grow into a bitter old man. Though it is hard to imagine such a bitter young man not growing into a bitter old man unless he dies young, and his counter to the good advice he receives is convincing: “It’s futile, pointless, utterly vain to forgive someone who feels that she has never done anything remotely wrong.”

Chin is very acute on how a sense of worthlessness was inculcated in him by his aunt. “Hid and found” about the impossibility of the vocation of writer for a Chinese physician’s son, and “The beginning of my worthlessness” are the most sustained and powerful essays in this collection of memories of growing up deviant/deviate in Singapore. They make me wish that he would have written a memoir, rather than the buckshot of autobiographical pieces, some of them very wispy and others forced, in his two collections of essays (Mongrel and Burden of Ashes).

With the onset of puberty at age 13, he was putting other initially repellent things in his mouth, cruising restrooms for sex even while spending years “praying for forgiveness and trying to purge my homosexuality through prayers and Bible study…. There were a few nasty encounters, brutal and painful fucks, near rapes, but through it all I never thought that I had the ability to say no.” Deference to the wishes/demands of adults? Filial piety? Well, perhaps once a contact was made, but I doubt that anyone ordered him to frequent the locales where cruising for sex took place—the locales where he knew that cruising for sex took place, the locales where he went for excitement, seemingly including the excitement of being victimized.

The second, shorter part of the book focuses on white men who have disappointed him as lovers, including two European diplomats and a Swedish psychologist while he was a teenager in Singapore. Here and elsewhere, he strikes back at white men who used him for a while and then found younger and/or more handsome and/or more pliable successors. Again, I think that putting the pieces together in chronological order might provide greater insight (to the writer, as well as to the reader), though “repetition compulsion” is a label that could easily be applied to most people’s sexual histories.

Creative Commons

Chin is a master of witty revenge, as in his lacerating poem “ex-boyfriends named Michael” (included in Bite Hard). The most interesting piece in the post-family part of Burden of Ashes is “Opercuthalousas” (a lexicon for blindness) with its alphabetical order. Chin manages something of a narrative within this artificial order.

Justin Chin has considerable gifts as a writer, but he is getting too old for disjointed collections of petulant bursts. I don’t know if it is reasonable to expect him to try to understand those who hurt him or who have hurt him, and to stop whining, but I wish that he would develop characters other than himself (and even that often seems to be a type more than an individual person) and dare to try a sustained narrative—if not a novel or a memoir, at least a novella…or an epic poem that fits the sequence of betrayals by those who have said they loved him into something less random than the very uneven miscellany of anecdotes in Burden of Ashes.

See my 1993 review of Chin’s And Judas Boogied Until His Slipper Wept here.

published on CultureDose, 3 June 2002

©2002, 2016, Stephen O. Murray