The Boys in the Band

The Boys in the Band

by Mart Crowley

Published by Farrer Straus Giroux

Published 1968

Theater (plays)

160 pgs. • Find on Amazon.com

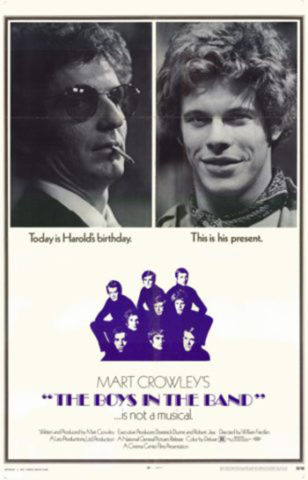

Film directed by William Friedkin

Released March 17, 1970 • Find on IMDb

Reviewed by Stephen O. Murray

January 18, 2012

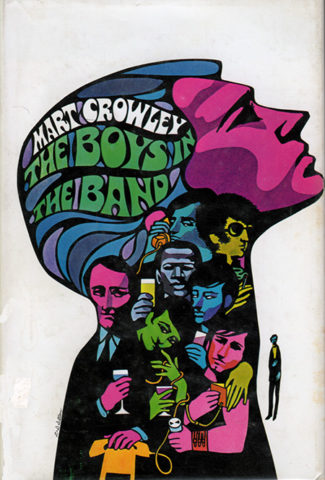

(Cover image from Secker & Warburg first edition, London, 1969. Jacket design by Diane and Leo Dillon.)

Mart Crowley (born in Vicksburg, MS, in 1935) is a “one-hit wonder,” the hit being the 1968 Off-Broadway play The Boys in the Band. He produced the movie version with the New York cast. The 1970, movie was directed by William Friedkin (born in Chicago in 1935), who would soon become much more famous, winning a best director Oscar for The French Connection (1971) and nominated again for the big box-office hit The Exorcist (1973). I think both of those hits were overrated and have not aged very well. Friedkin directed some interesting if uneven other movies (Cruising, 1980; To Live and Die in L.A., 1985; Rules of Engagement, 2000). During the late-1970s he was married to Jeanne Moreau; since 1991 he has been married to Sherry Lansing (producer of Fatal Attraction and The Accused). I don’t consider him an auteur in general (though he has exercised quite a bit of control in writing and editing as well as directing movies), and though he did much to make Boys in the Band cinematic, authorship of the characters and situations was definitely Crowley.

The play appeared before the 1969 Stonewall riots that were misappropriated as the name for the gay liberation generation, the movie released a year after them. The play was significant in that it was written by an openly gay playwright and mostly cast with openly gay New York actors (Cliff Gorman may have been the only one who was not gay, but he was so convincing as the nelly Emory that many people assumed he was not acting; having won an Obie for Emory, Gorman went on to star as Lenny (Bruce), though the part in the movie adaptation went to Dustin Hoffman). And it broke with (and even commented on) the 1950s and 60s convention that gay characters had to die (whether by murder or by suicide).

When the movie came out (and it did reach the provinces, contrary to someone’s assertion in the DVD retrospects) I didn’t know any gay people or that I was gay—although I had been in a love relationship with a male of my age for more than a year before seeing the movie. I can see that the nastiness and unhappiness on display may have scared many who were asking themselves if they were gay, but in those days, when there were not positive images, the movie was a revelation that there were gay people and friendship networks. I was more intrigued than frightened by the freak show aspects. I’m pretty sure that then as now the character I identified with was Donald (Frederick Combs), the bookworm who has a sort of ongoing carnal relationship with the host of the birthday party, Michael (Kenneth Nelson), a self-hating Southern sweater queen who is so nasty to everyone that it is a wonder anyone would turn up for a party he hosted.

The guest who shakes up Michael is his college (Georgetown) roommate Alan McCarthy (Peter White) whom Michael does not want to know what kind of friends he has, though he is also convinced that Larry is a closet queen (and may be right, though if so, Larry is scared back or deeper into the closet by exposure to Emory’s effeminacy).

The first half of the play and movie is mostly comic with a young, dumb (and presumably full of something that rhymes) midnight cowboy (Robert La Tourneaux) arriving ahead of schedule and singing “Happy Birthday” to the wrong man. Harold, the acerbic “Jewish fairy” (his self-description), arrives later and is Michael’s match (or outmatch) in the games of putdowns and truth games Michael plays. As Harold, Leonard Frey has considerable coiled menace and glides like a skater, except slowed way down.

Donald and Michael are sort of a couple. Hank and Larry (Laurence Luckinbill, Keith Prentice) comprise a masculine/ist couple with tensions about Larry’s need for variety. Larry, nonetheless, is jealous about Alan’s bonding (hitting on?) Hank.

Donald and Michael are sort of a couple. Hank and Larry (Laurence Luckinbill, Keith Prentice) comprise a masculine/ist couple with tensions about Larry’s need for variety. Larry, nonetheless, is jealous about Alan’s bonding (hitting on?) Hank.

The second half is overwrought melodrama as Michael presses a “game” in which his guests must call (on a rotary-dial phone) whomever they have most loved. Harold refuses to play. Emory and the charming black bookstore employee Bernard (Reuben Greene) relive crushes from which they have not recovered. Push comes to shove of Alan. Michael regrets what he has done, is comforted by Donald, and goes off to early Mass (embrace of the church that condemns him is a prominent part of his self-hatred).

I like the opening montage of the “boys” before/en route to the party and the blocking (holding back on close-ups) in Michael’s apartment and its terrace. I think the sudden cloudburst is ludicrous (light rain never seems to occur in movies!) and the workings out of the second half creaky and a bit tedious (I blame Crowley not Friedkin). Michael becomes very loathsome (clearly, Crowley intended that), and everyone else seems sympathetic in comparison, not least Harold.

I don’t have any experience of urban gay parties of the 1960s but still wonder about this collection of types being friends (Bernard and Emory, yes, but Harold and Michael?). I am glad that I have never been to a party like the one in Boys in the Band (or the one in Who’s Afraid of Virginia Wolf? which also has eviscerating “party games”). None of the parties I have ever attended or thrown—gay, academic, both, other—has involved “truth games” or such dramatic conflicts and revelations (taking off clothes is another matter!).

For all its (considerable!) melodramatic excesses that seem too “stagy” even for gay drama queens, the movie has historical interest as a sort of coming out of 1960s-style homosexuals, memorable performances, and some memorable lines. The DVD has a three-part documentary. The first part, on the play, and the second, on the transfer from stage to screen, are substantial. The “40 Years On” part is brief though poignant in unreeling the early deaths (mostly form AIDS) of two-thirds of the cast members (no one seems to know what became of Reuben Greene). Tony Kushner supplements Friedkin, executive producer Dominick Dunne, and the surviving cast members (Luckinbill and White) across all three parts. (BTW, Crowley says he has been obsessed by Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope most of his life. That movie had similar homosexual guilt and a sadistic exposer of Truth, played by James Stewart). No one addresses the charges made by Vito Russo (who was a leader in the attempt to keep Cruising from being made) that Crowley wrote “perfunctory, easily acceptable stereotypes” and “lots of zippy fag humor that posed as philosophy.” But, unlike as with Friedkin’s Cruising (1980), the political critique of Boys in the Band built after the movie’s release.

For all its (considerable!) melodramatic excesses that seem too “stagy” even for gay drama queens, the movie has historical interest as a sort of coming out of 1960s-style homosexuals, memorable performances, and some memorable lines. The DVD has a three-part documentary. The first part, on the play, and the second, on the transfer from stage to screen, are substantial. The “40 Years On” part is brief though poignant in unreeling the early deaths (mostly form AIDS) of two-thirds of the cast members (no one seems to know what became of Reuben Greene). Tony Kushner supplements Friedkin, executive producer Dominick Dunne, and the surviving cast members (Luckinbill and White) across all three parts. (BTW, Crowley says he has been obsessed by Alfred Hitchcock’s Rope most of his life. That movie had similar homosexual guilt and a sadistic exposer of Truth, played by James Stewart). No one addresses the charges made by Vito Russo (who was a leader in the attempt to keep Cruising from being made) that Crowley wrote “perfunctory, easily acceptable stereotypes” and “lots of zippy fag humor that posed as philosophy.” But, unlike as with Friedkin’s Cruising (1980), the political critique of Boys in the Band built after the movie’s release.

Also see Stephen O. Murray’s essay, “Maybe only one hit, but Mart Crowley wrote more plays after The Boys in the Band” here.

first published by epinions, 18 January 2012

©2012, 2017, Stephen O. Murray